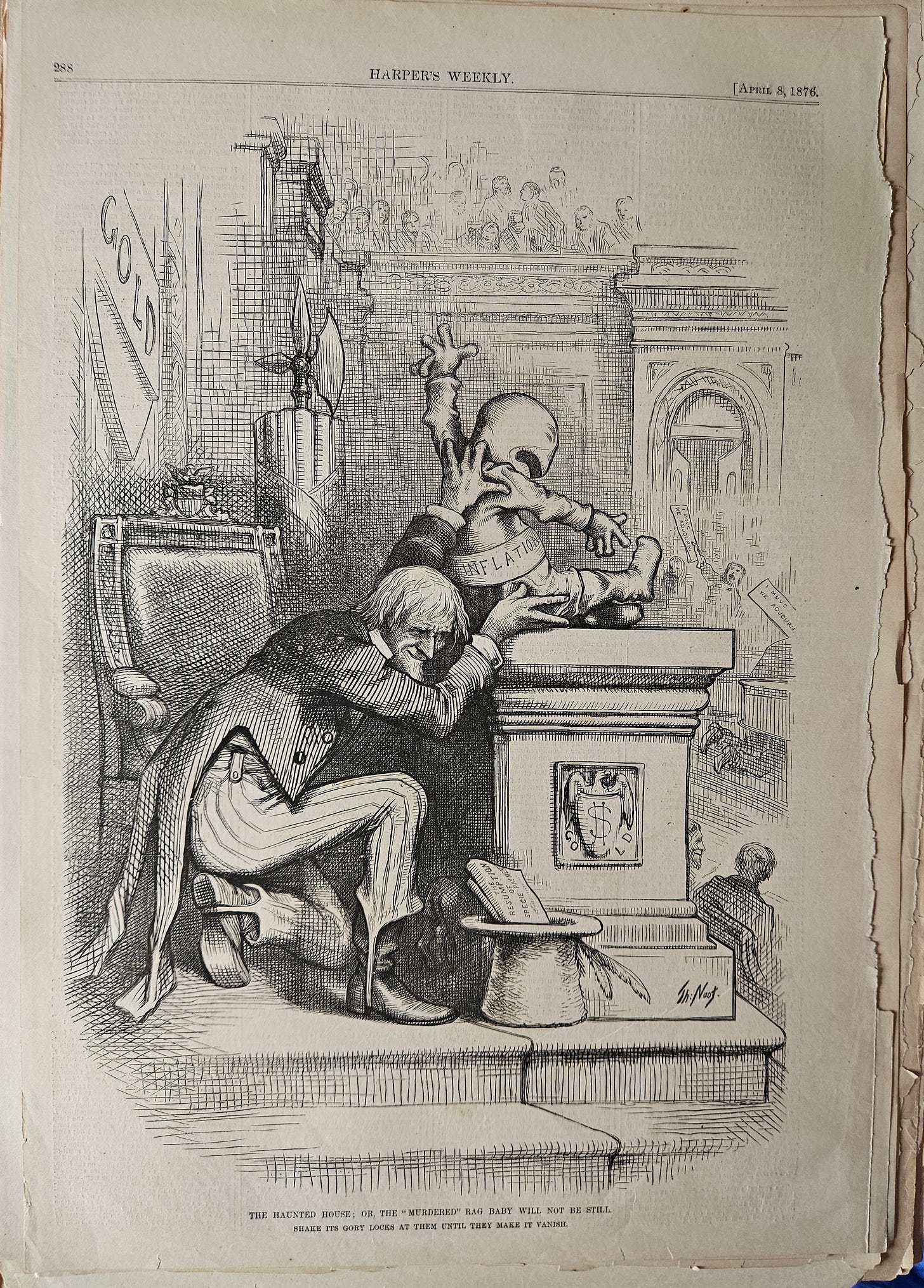

"The Haunted House" by Thomas Nast, from Harper's Weekly, April 8, 1876 (Nast's grandson's observations included below...).

https://www.americanheritage.com/life-and-death-thomas-nast

"The Haunted House; or, the Murdered Rag Baby Will Not Be Still" - Shake It’s Gory Locks At Them Until They Make It Vanish” —about Uncle Sam & Inflation.

From ART MUSEUM, University of Saint. Joseph

Nast’s first use of the rag baby was Harper's Weekly, Septemeber 4, 1875 as a symbol for inflation. Allen G. Thurman, Democratic senator from Ohio and a “hard-money” advocate for most of his career, discovers the rag baby, crying for more greenbacks, deposited on his doorstep by his state party. Like fiat money, the rag baby has no solid core. The cartoon’s title plays on alternate meanings of “irredeemable” – the inflation rag baby is beyond correction and greenbacks can no longer be exchanged for gold.

Nast often employed a serial approach to build upon and amplify the effect of individual cartoons. About a month later (October 9) he showed Governor Samuel J. Tilden of New York, backed by his state’s Democratic Party platform for hard money, choking the rag baby on the Ohio senator’s threshold. Thurman peers cautiously from a window as a woman representing the Ohio Democratic Party shouts “Holy Murder!” to summon the police. Although Tilden became the Democratic presidential nominee in 1876, the final election was awarded to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes by the Electoral College Commission appointed to resolve the deadlocked election.

Allen Thurman would come to embrace the “soft-money” position represented by the rag baby, a move seen by Harper’s (and Nast) as a calculated bid to win his party’s presidential nomination in 1880. [Text prepared for exhibition - Money Matters (2016)]———

(And here’s aftermath about Tweed and Nast’s later life, told by his grandson). From American Heritage (by Nast's grandson)

The Life And Death Of Thomas Nast, October 1971 by Thomas Nast St. Hill.

When Tweed died in New York City’s Ludlow Street Jail in 1878, every one of Nast’s cartoons attacking him was found among his effects.

Thomas Nast’s part in overthrowing the Tweed Ring added to the nationwide prominence he had gained during the war. He had become a political power, every Presidential candidate that he supported having been elected. Even General Grant, upon assuming the Presidency, attributed his election to the “sword of Sheridan and the pencil of Thomas Nast.”

Grant contemplates a third term (Democrat Donkey…)

The symbols that Nast originated during this period were to outlive their creator. Between 1870 and 1874 the Republican elephant and the Democratic donkey made their first appearances. Both were conceptions of Thomas Nast, based on the fables of Aesop. Today’s familiar images of Uncle Sam, John Bull, and Columbia also were conceived by Nast during this period.

My grandfather was a controversial character. Whereas the staunchly Republican Union League Club of New York honored him for his ardent devotion to the preservation of the Union, the New York World in 1867 accused him of bigotry and pandering to the “meanest passions and prejudices of the most unthoughtful persons of the day.” To Nast all things were either black or white. There was nothing in between. He was absolutely merciless in his attacks upon those with whom he disagreed. The Ku Klux Klan, anarchists, Communists, corrupt politicians, and even the Irish and the Catholic Church were among those upon whom he vented his wrath. Obviously one’s opinion of the artist depended largely upon whether one agreed with his views or not.

By 1877 my grandfather was a relatively wealthy man with an unusually good income in terms of that day. Not yet forty years old, he had just about everything that he could wish for —a nationwide reputation for integrity, a lovely home, a devoted wife and family, and financial independence. Sarah Nast had contributed greatly to her husband’s success. She regularly read to him as he worked. Shakespeare and the Bible were the inspirations for many of the artist’s drawings, and Sarah Nast often supplied the ideas and captions for them. My grandmother was a charming hostess and entertained her husband’s distinguished friends graciously and unostentatiously. General Grant and his wife and Mark Twain were guests on more than one occasion.

As the result of his national prominence the artist frequently received offers to lecture, few of which he accepted. It was an activity that he cordially disliked. For one thing it kept him away from his home, where he now did all of his work. Equally important was the fact that he suffered so acutely from stage fright that he often became ill before an appearance.

Some offers were hard to refuse, such as one extended by the Boston Lyceum Bureau offering ten thousand dollars for a ten-week tour. But at the time the artist was too busy with his assignments for Harper’s , work that he much preferred. Two years later he was approached again, with an offer of “a larger sum for a hundred lectures than any man living.” But Nast again declined.

In 1877, Mark Twain, Granddad’s good friend, proposed in a letter a plan that must have been very tempting: My Dear Nast: I did not think I should ever stand on a platform again until the time was come for me to say “I die innocent.” But the same old offers keep arriving. I have declined them all, just as usual, though sorely tempted, as usual.

Now, I do not decline because I mind talking to an audience, but because (1) travelling alone is so heart-breakingly dreary, and (2) shouldering the whole show is such a cheer-killing responsibility.

Therefore, I now propose to you what you proposed to me in November, 1867, ten years ago (when I was unknown), viz., that you stand on the platform and make pictures, and I stand by you and blackguard the audience. I should enormously enjoy meandering around (to big towns—I don’t want to go to the little ones) with you for company.

My idea is not to fatten the lecture agents and lyceums on the spoils, but put all the ducats religiously into two equal piles, and say to the artist and lecturer, “Absorb these.” …

Call the gross receipts $100,000 for tour months and a half, and the profit from $60,000 to $75,000 (I try to make the figures large enough and leave it to the public to reduce them).

I did not put in Philadelphia because P____ owns that town, and last winter when I made a little reading-trip he only paid me $300 and pretended his concert (I read fifteen minutes in the midst of a concert) cost him a vast sum, and so he couldn’t afford any more. I could get up a better concert with a barrel of cats.…

Well, you think it over, Nast, and drop me a line. We should have some fun.

Yours truly,

Samuel L. Clemens.

It seemed a fascinating plan, but again my grandfather had no inclination to leave his home and family, and so he again regretted.

By 1879 Thomas Nast was beginning to get restive. Changes in management at Harper’s had resulted in less freedom to express his own views. A new generation of publishers did not wholly agree with what they considered their artist’s tendency to advocate startling and, in their opinion, sometimes radical reforms. Then, too, with the introduction of new techniques in reproduction, the hand-engraved woodblock, which Nast had used to such advantage, had become outmoded and the new methods were less suited to his style. Consequently, as Nast’s drawings appeared less frequently in the Weekly , he took advantage of the opportunity to travel and invest his savings. While my grandfather would have been the last to realize it, he had, at the age of thirty-nine, reached his peak.

Nast had learned little about finance during his career as an artist, as would soon become apparent. An investment in a silver mine in Colorado proved unprofitable and became a drain on his resources. But in 1883 his financial problems seemed about to be over. His good friend General U. S. Grant had, after retiring from the Presidency, invested all of his savings in a Wall Street firm headed by Ferdinand Ward, a New York investment banker. Grant’s son, who lacked financial experience, was made a junior partner to look after his father’s interest. The venture prospered to such an extent, or so it appeared, that General Grant offered Nast an opportunity to participate, a privilege accorded only to a select few. This seemed the chance to recoup his mining losses, so the artist sold a piece of property and invested the proceeds in the firm of Grant and Ward. The generous dividends that ensued encouraged Nast to take his family abroad for a much needed rest.

It was not long after his return, however, that headlines in his morning paper announced that Grant and Ward had failed. It seemed incredible in view of the optimistic reports and liberal dividends he had been receiving. But the fact was that Ferdinand Ward had proved to be an unscrupulous manipulator who, in order to maintain the fiction of profitability, had been declaring dividends out of capital funds until there was no more capital left.

My grandfather lost everything that he had invested, while General Grant lost even more. Grant had personally guaranteed one of the firm’s notes a few days before the failure was announced and, in order to help pay off the note, had to sell everything he could get his hands on, including military trophies and souvenirs from all over the world. Not until Grant’s memoirs were published posthumously was his family able to pay off all of the General’s debts.

The disenchantment that followed Nast’s first and final experience in Wall Street was revealed in several of his pictures. One, a merciless and funny self-caricature in oil painted eighteen years later, depicts the artist’s complete bewilderment and despair at being duped. (This painting, on loan from the Smithsonian Institution, hung in the White House office of Daniel P. Moynihan during the time he served as a counsellor to President Nixon. It was known among Dr. Moynihan’s colleagues as Nast Contemplating the “Bust” of Ward .)

Relations between Nast and Harper’s did not improve during the Presidential campaign of 1884, when the cartoonist found himself unable to support James G. Blaine, the Republican candidate for the Presidency. For the first time Thomas Nast campaigned for a Democrat, caricaturing Blaine as the “Plumed Knight.” Grover Cleveland, the Democratic candidate whom Nast supported, was elected.

In 1886 came the end of Thomas Nast’s association with Harpers Weekly, a magazine that he had helped make famous and in which he had made his reputation. In the quarter century of the Nast-Harper’s relationship the nation had passed through a turbulent period, and Nast’s drawings in the magazine would provide a vivid pictorial chronicle of those years. But in terminating his connection with Harper’s Nast lost his forum, while at the same time the Weekly lost its political importance.

Several years later my grandfather tried starting his own paper, but this venture, too, failed, leaving the artist heavily in debt. Nast consoled himself, however, that he had lost no one’s money but his own. Now came the time when horses and carriages had to be sold, faithful servants dismissed, and a mortgage placed on the house.

It was like manna from heaven, therefore, when in 1889 his old friends at Harper’s proposed that he get together a collection of his Christmas drawings for publication in book form, a very Christmaslike gesture and one that my grandfather gratefully accepted.

Thomas Nast’s book Christmas Drawings for the Human Race was published in time for the 1890 Christmas season. It contained pictures that had appeared in Christmas issues of Harper’s over a period of thirty years as well as some additional drawings made especially for the book. Clement Moore’s “A Visit from Saint Nicholas” was again the inspiration for many of the new Christmas drawings, and Santa Claus was now depicted as the very embodiment of merriment and good cheer.

———-

Nast created the Republican elephant and Democrat donkey!!! I had no idea. I wonder what contemporary cartoonist, if any, even comes close to his creative influence.