The making of MORGANS CAKE continues... The "father" character, played by improv vet WILLIE BOY WALKER ("THE 5TH WALL," etc.), performs his hilarious "DRAFT STORY"––which brings it all together!

https://vimeo.com/ondemand/morganscake (see TRAILER here)

(Excerpted from book, THE MIRACLE OF MORGAN'S CAKE––Production Secrets of a $15,000 IMPROV Sundance Feature").

\Finally, as I felt the energy winding down at the “Steak Dinner” scene, I commanded to Rachel, You’re cold, you’re going in. She repeated the words (I'm cold...) and everybody sort of ushered her from the table, a flock taking care of the new mother-to-be (Morgan stayed in his seat, exhibiting very good instincts). With Morgan still seated, I could wrap up the scene with a gradual fade-out tail if I wanted, letting the information seep in a little deeper on the side of Morgan’s life’s problems. After staring into space for a minute, taking a drink, he pulled back his chair and left the table (I must have given him the command, Leave).

Willie Boy Walker, telling his 10+ minute real-life story about the Vietnam-era draft.

Because I had shot a lot of footage at Rachel’s house, and we were basically done for the day, I decided to keep the camera in place (tripod and camera locked down), to shoot a little bit more of the now-deserted outside table, abandoned plates and glasses, where all the “pregnancy” discussion had taken place. Since I hadn’t moved the camera at all, I waited until darkness had descended and then shot the same composition, giving me options in editing for a natural fade-out to artificial back porch lighting (Morgan would just fade out, slowly becoming transparent and then invisible...leaving the table and dishes). With a final click-off of electric lights (I asked Mr. Pond to do that) the scene fell to darkness. A lab-controlled fade-out would finally ease it out to total black.

With a big scene it makes sense to have a gradual transition in place, extending the magic that you worked so hard to create. A sudden jump to other scenes may stun your audience, ruin the nice editorial flow, knock the elegance out of your sequence. So just shoot some extra stuff, without apologies, so that you have some useful cutaways and “nothing” shots to incorporate later into the final cut.

Making a Location “Real”

The third day of shooting brought Willie Boy Walker back to our little one-room command post, where he supposedly lived with Morgan. Willie sat at the desk and began fiddling with all the art supplies we had brought in from his house in Oakland. Since the old $35 desk I’d bought had an indented space on its surface to accommodate a typewriter, I had constructed a wooden box with hinged lid to fit snuggly into that space (one of my Pre-Production carpentry tasks). Willie was happy to store his supplies in there, play along with this fantasy of living a painter’s life – in a hovel. It was a comforting feeling to see Willie handling the brushes, choosing paper and paints, to watch as the actor actually became the character my movie needed.

Willie had earlier brought over some framed photos of himself from art school days, along with a current artwork to hang on the wall, helping him own the space even more (the acrylic work, a picture of a man smoking a cigarette while a dolled-up woman stares ahead, had the inscription “Everything is so different, he thought,” written along the bottom border. I again noted those interesting props as I started to frame the scene and, with Kathleen’s help, set up the lights. I made a mental note to try and use that painting and its commentary someplace in the movie; I later incorporated it in an important narration by Morgan, where he wonders what his life will be like as an adult.

And so, Willie kept busy making some art while we worked out last-minute preparations to shoot Willie’s draft story, in which he’d tell his son how he avoided military service during the Vietnam war; ie. failing his physical by going without sleep, taking mind-altering drugs, and putting peanut butter in his pants.

Not Directing "THE BIG SCENE"

Since the essence of Morgan’s Cake was Morgan’s aversion to being part of a military force, it was clear that Willie’s draft story about his crazed antics at the Military Induction Center would be a perfect counter-point in the story. Willie’s draft experience, which I had vaguely remembered from audio taping it once ten years before, made him perfect for the role of Morgan’s Dad. All I needed to do, as director, was supply him with complete encouragement (Willie, like others I know, doesn’t function well under criticism), while trying to insure that his storytelling hit the marks, was clear and concise- enough to be completely shot-to-one – a full roll of 16MM filmstock – limiting the take to approximately 10 1/2 minutes. (With DV, of course, a moviemaker can shoot a continuous 60-minute take with no problem except disk space!). Yes, Willie’s monologue would have to be a tour-de-force to hold up that long on the screen (10 minutes of a static shot!), but I knew that if anybody could do it, my old friend could.

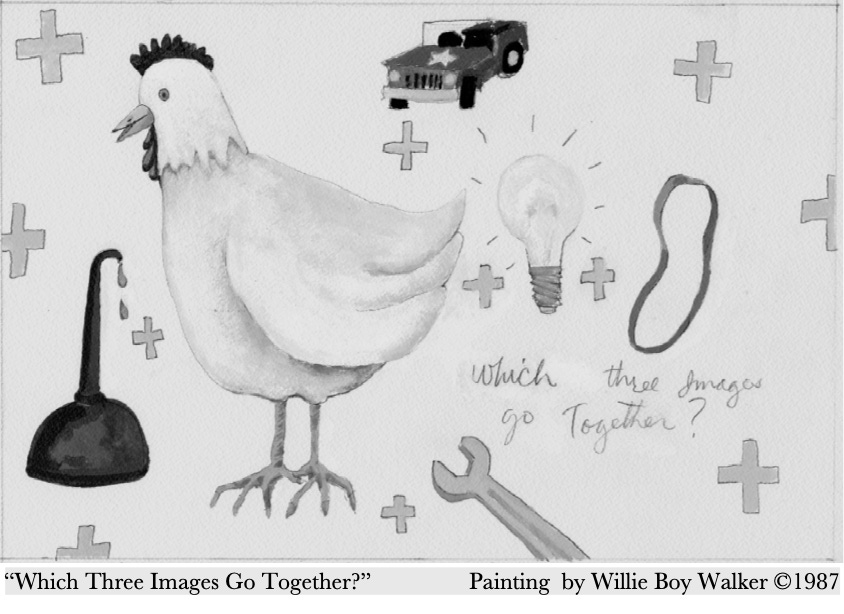

After Willie had agreed to do the part, he’d gotten himself into the mind set of those be-gone art school days of the late 1960’s and had produced a beautiful painting that represented the army’s intelligence test which he’d been given. He showed the picture to me that morning of the shoot and said he’d like to use it as a prop. I immediately laughed at the images, before I even knew their significance.

There was a collection of seemingly unrelated rendered objects filling the white paper; a chicken, a light bulb, a wrench, a jeep, a rubber band and an oil can. In the middle of the composition, Willie had carefully written in with paint the Army’s question for the test; “Which three Images go together?” It was a terrific prop and a delightful surprise gift to the production that morning. We would certainly figure out how to incorporate it into the shots.

Before the draft story could be shot, though, we needed

to illuminate the darkened area of the room where Willie was seated. Kathleen placed a soft-light near the front window and aimed it back into the room. Setting up an artificial light aimed in the same direction that natural light floods in, keeps the lighting integrity of the location intact. Willie sat at the desk wearing a beret I had found as a prop. He looked great and seemed ready to act his part

When the lights were almost set, and I was getting psyched to start shooting, Willie suddenly exclaimed, “Just don’t try to direct me.” Oops. Err...ah...OK. When working with old friends you may experience a moment like this where familiarity will impact your moviemaking momentum. I didn’t take his directive very seriously, but it did shut me down emotionally for a second or two. I had to regroup, realizing that in Willie’s case I must work less aggressively as “El Director.” I needed to be in control without showing it. In the back of my mind I knew I would never let him get out of his chair until he had told his real-life draft-evasion story to my complete satisfaction. But I had been warned.

To begin with, we shot Morgan entering the office with the video camera on the pole, the item he had been forced to borrow from the “rich kid” at the beach. I gave Willie instructions to be annoyed when he saw that Morgan hadn’t returned the device yet, worrying that it could cost him money that he didn’t have, if it should break.

Since Willie is a dad in real life, I figured he could easily relate to the paranoia of such a moment. Morgan, of course, knew how to defend himself – Don’t worry about it. I’m going to bring it back on Friday. And Morgan was also adept at altering the focus of the conversation What are you drawing...oh, that’s a nice drawing... Morgan gave the needed reference to the military test painting, to allow me to set up the next cut. Taking the lead, Willie introduced the painting as the gist of the military test as he remembered it, and challenged Morgan to come up with the correct answer.

I designed a few cuts into the series of shots that morning to show the painting close-up, but finally had to re-shoot the image in 16mm at the art department of Palmer Films Lab. For coverage, I also shot it with my Hi-8 video camera micro lens, adding those super close-up shots to the montage of color video beach images (from the overhead pole), and street shots (the Berkeley man's draft story) to be shown later on John Claudio’s “rich kid” VCR.

NOTE: Save all props from the shoot, in case you need them later to correct a mistake or make an improvement in a sequence. Store them in a well protected, water-proof container where you can get to them quickly, when you finally realize their crucial importance.

Following a funny riff based on Wille’s “pop quiz” painting, Willie launched into a thorough discussion about warfare and the status of conscientious objectors. Suddenly I felt that the wide shot had been running long enough and I called for a cut. Freeze! Everybody hold their places and don’t move, while I change camera angle.” I set up a new framing of Willie’s face, medium-close- up, to prepare for his draft story monologue.

OK. I couldn’t “direct” Willie, but I could certainly say Action. As we rolled along I could sense that the first take was off-kilter, the words and descriptions sloppy, not striking as clear images. Remember, I was the one operating the camera, so I could view the performance from the perspective of an audience. I called Cut to Willie’s dismay, and told him he was running it way too slow, not mentioning the fuzzy story telling itself. He was definitely taken aback, got mad, and spouted, “OK! OK! Start it again!”

Somehow the added edge of anger helped him clean up his act. In the second take he got on a great roll and kept up a snappy pace as he spewed out all the crazy details of his interaction with the military. As Willie fell into his story-telling groove, Morgan began howling with laughter and it got harder and harder for me to also not laugh. There I was, looking right through the lens at Willie’s tightly-framed, comic face, as he lay in one hilarious incident after another.

I could feel a horrible giggle rising from deep inside somewhere, going against all the mental discipline I was trying so desperately to contain. Finally I just couldn’t suppress a laugh any longer – I could feel it escaping from my lips! So I closed down the eyepiece shutter (mandatory to avoid letting light leak onto the exposed film while shooting an Eclair ACL), and placed my little finger directly in my mouth, biting down hard. I almost had to bite my finger off to avoid ruining my own precious shot. With hardly a minute of film stock left, Willie wrapped up the incredibly hilarious story by referring back to his watercolor painting of the army’s intelligence test. You’ll have to watch the movie to learn what three things he said fit together.

See full MORGAN’S CAKE movie (including “3 things that fit together’ footage) HERE.

More Nothing-Shots & Cutaways

On Day-Three, I finished out the morning with “nothing” shots of Willie at the desk as seen from a wide perspective. Shooting from back in the hallway I filmed Willie working on a new watercolor painting for a while, then instructed him to get up, stand and putter around, daydream, finally walk to the far window. I yelled something like, No! Over more to the right! when he was too much out of the framing I wanted. Then I gave him the voice command, Return to desk and do more painting. Through the doorway only some of his profile – the side of his head and back – could be seen, the desk completely blocked by the wall.

Then, positioning the camera-on-tripod inside the room, I filmed his painting from a closer angle, then shot him straightening up his pictures on the wall (I first made them crooked of course, so he could tidy them up). These “nothing” shots, where no particular action is happening – not the solid “meat-and-potatoes” shots with meaningful dialogue that are the major building blocks – are often the very images that save the movie in the editing room and give the film a certain richness. So (not to repeat myself too much...) make sure you shoot a few such atmospheric images, always paying attention to the ambient sync sounds you’re recording, as you build your feature-length narrative.

To make sure that I’d have a cutaway later during editing, I also shot a medium-close-up of Morgan’s reaction to Willie's hilarious draft story. If I needed to speed up the telling of the story, a cut to Morgan would allow me to jump past some parts of the material. As director, I had to cajole Morgan into laughing as hard as I’d heard him do off-camera during Willie’s actual performance. Finally, with Willie’s help, I got a shot of Morgan laughing to the point of tears.

Morgan, age 18, laughs heartedly, while hearing Willie Boy Walker’s “DRAFT STORY.” (Morgan Schmidt-Feng’s website—he caught the filmmaking bug (see reel) and his FILMSIGHT productions!)

By noon of Day-Three (and another round of Jumbo’s burgers at everyone’s request) I had shot Willie’s big scene, had introduced most of the main characters, and was beginning to get that superstitious feeling that if things kept going this well...the movie might be a good one. But I didn’t want to jinx the production by saying that out loud, in case the movie gods were listening.

Yes, things were going my way (fingers crossed), and there was still a lot of work ahead. Next we’d go to artist M. Louise Stanley's (Lulu's) studio and cover Morgan’s interaction with “his mother,” at the same time reintroducing the woman painter, Lee Chapman, from the office building, who had earlier relayed the mother’s terse message when she saw Morgan in the hallway with his surfboard.

————-

Hey he comes with a song and great lyrics by the great.Townes van zandt even ...hey Willie boy watcha gonna do when the turns red and the trees blue tell all my puppies and turtles and things

". . . and was beginning to get that superstitious feeling that if things kept going this well...the movie might be a good one." There is no mistaking that feeling that you've plugged your creativity into The Mystery, where you just need to pay attention and unwrap the Gifts as they arrive, and have the good sense not to tamper with them, but honor them as the miracles they are.