The 'long-and-winding-road, as I transitioned from FINE-art to MOVIE-art. (Actually THE ACT of taking a video class happened in an instant (of CHANGING my mind...which CHANGED my life!).

(My "12 DEAD FROGS" memoir in paperback): https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0777FHXX2

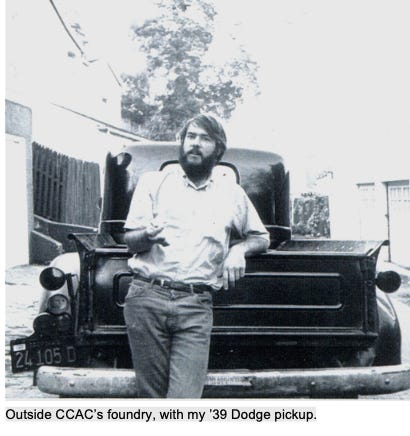

Probably the most insane part about those days was that I was making up my own rules in life and they were working! I had needed a free studio and had found it, almost 400 square feet in which to do my artworks. And my 1939 Dodge had been dropped right in my lap for $35 that SAME Day in Berkeley (story coming up!). (I finally spent a total of $141, including lunches for a mechanic friend, to get the Dodge running). It was the sale of this vehicle for my EMERALD CITIES production that gave me my book title, FEATURE FILMMAKING AT USED-CAR PRICES.

I had also applied my search for free (or affordable) housing to neighborhoods close to CCAC, finally locating a single room with a bath down the hall for $25 per month two blocks from school. I found this great rental after almost three weeks of continual knocking on doors, asking neighborhood residents if they knew of any cheap housing available. And with two “TA” (Teacher’s Assistant) shifts at the foundry, bringing me an income of around $80 per week, the ratio of that earned income to my rent was almost 13:1. Applying that ratio to current single- room rents (in Berkeley it isn’t unheard of for a room to go for $500 per month), I would have to earn around $7500 per month now, to get that same wonderful rent-to-income relationship. My tuition was also covered, through the full scholarship which had just been awarded, so the cost of my education was free at that time.

GRADUATION DANCE (1970)

As December 1970, approached I was faced with many incomplete grades which I had accrued (I had just stopped going to classes, deciding only to pour metal, produce sculptures), including the five classes in which I was currently enrolled. I had to somehow leap the final hurdle of completing all those classes to graduate. And it was crucial, because I had already applied to graduate school, armed with a letter from Charlie Simonds, the “toughest teacher at the school,” that said, “Rick is the best sculptor now working at CCAC.” I had to finish!

I began by going up to the dean of lower division studies and asking him if he could possibly wave my Ceramics class. I explained that I used clay all the time for my original forms in sculpture in the foundry, making plaster molds off of them for my waxes, etc., etc., and amazingly he said, “Sure Rick, no problem.” He reached into his pocket, removed a fountain pen, uncapped it, and signed the class card that I had brought along. One class gone and nine to go!

I also asked him if he could wave my Anatomy class (a class that took hundreds of precious hours out of your life, as you rendered bones and memorized their names.). Again, he said, “Sure,” agreeing to cancel that one as well. (Two down!). So, with the swipe of his pen he had erased classes that would have been impossible for me to complete in the designated time before graduation.

Next, I had to approach some academic teachers, who I feared wouldn’t be so lenient on me. The Psychology professor didn’t quite understand why I should be allowed to just skate through his course without doing any of the prescribed work. Finally, he asked me to meet him at his apartment and said we would get the thing settled. It never occurred to me that there was anything sinister about his request, and there wasn’t. He stood leaning against the small fireplace’s mantel in his tiny living quarters off College Avenue in Oakland, and after hearing me speak for a while, about my life and artworks, he asked me if I thought a “B” would be an appropriate grade under the circumstances. I said “Of course!” So that class (number three!) was also magically completed.

But the Pre-Columbian Art History teacher was a much tougher sell – and unapproachable. She was the kind of personality you avoided, with a tough stance, severely adult-looking, always wearing a man’s tailored suit to class, no smiles, ever. I didn’t dare attempt to persuade her to grant an unearned passing grade. So, before the final test, I hastily read the textbook in the library for about two hours (didn’t have my own copy) and took the test. Somehow, I got a “D-” and barely passed. But that wasn’t good enough for her. She said because I was one of three marginal grades that would have to be averaged, she further required an oral test in the coming week. And, she said I owed her a completed project. So, there was some major strain and time involved. In the foundry, I quickly copied the form of a frog artifact that had been pictured in my textbook, modeling it straight to wax. Using a method called shell casting (which was described as the method used by South American natives to produce the golden frog pictured in my textbook) I surrounded the wax with painted-on plaster coats, then held the dried pod-shaped mold over the blast furnace until all the wax melted out. Molten red brass (which I hoped would look a lot like the gold of the original) was poured into the cavity and voila!

The teacher was delighted when I presented her with the mold, cracked open to reveal the famous pre-Columbian golden frog. Next were the orals. I studied for at least eight hours, trying to cram a semester’s worth of knowledge into one afternoon. And it worked! She let me know that I had only passed because the curve had been so low. The other students had actually been less prepared than I was. That completed class, fourth on my list, put me in the final stretch. Since the rest were studio classes (foundry, advanced sculpture, and my furniture design class), I was able to sail through and get my BFA (“With Distinction” no less), and continue on with graduate school at CCAC.

If it sounds like I got away with murder, and that CCAC teachers were unprofessional in voiding certain classes, let me say that it wasn’t quite so simple (or blatant) as it appears. Remember that I had made the commitment to produce as much art as I possibly could before I graduated. So I had worked consistently hard and created numerous well-crafted sculptures, winning spots in all-school shows, even tying with a sculptor friend, Dale Lanzone, for Best Sculpture at CCAC. So I had earned a good reputation at school, and several teachers were aware of my professionalism. If there was any doubt that I should be helped toward completion of my BFA degree by removal of a few secondary classes, Charlie Simonds’ written recommendation for my admittance to graduate school at CCAC was the clincher:

“The argument for extensive undergraduate academics generally accepts as a goal the diversification and humanization of the individual. Rick is both diverse and humanized. He is intensely concerned with the relationship between life and art. His posture on the personal level is honest and penetrating for he is an astute intuitive intellectual. This makes him an invaluable asset in the classroom. I believe that Rick does not need the benefit of further undergraduate study.” –Charles Simonds

LIVING LEGEND (1970)

Between the pressures I felt from having recently split from my wife, and the whirlwind insanity of completing my undergraduate curriculum, I was impatient with the added requirement of writing up my ’Project Description,’ then required for all graduate students at CCAC. Hadn’t I wasted enough time not doing some art? I had been accepted in the MFA sculpture program, with a full scholarship, and fortunately still had my TA jobs in the foundry, so I was in very good shape for economically surviving the 1-2 years of additional study. But I was extremely disinclined to accommodate school rules and regulations.

The school had requested that each student in the conceptual goals, and personal oeuvre, etc. Since I didn’t approach my artworks from that kind of verbal position, I felt ill at ease, dumbfounded for anything intelligent to say. Of course, in today’s more conservative art colleges climate I would have been hard-pressed to survive such academic requirements (I knew some talented artists back then – late’ ’60s – who simply quit instead). All I knew was, I wanted to continue creating some good sculptures, so that I would have enough work at graduation to have a gallery show (and perhaps make a living!).

After a few days of worrying, using up valuable time on this administrative problem, I went to the school library, sat down in front of an available typewriter, and typed out the following paragraph in less than ten minutes:

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

Ideally the graduate project should offer the serious artist an opportunity to work, unhindered by teaching responsibility or other job commitments, in a sustained effort continuing over at least a year’s involvement.

For my project I plan to produce enough elegant works of art to become a living legend before I graduate.

(Signed Richard R. Schmidt, and dated; December 11, 1970.

Charlie Simonds, by then my studio-mate as well as advisor (he and I shared a studio in East Oakland), OK’d my Project Description, adding his bold signature to the bottom of the document. The logic of my statement was there for the school administrators to see, if they looked carefully enough. I wasn’t really saying that I thought I could become a living legend! I was just trying to set a goal for myself, that had a wrinkle and a wink of humor in it. It was my intention to drive myself hard to do a lot of really good work, but not take myself too seriously. But the description I wrote hit the graduate administrators at several unexpected levels. It either gave them pause for thought, or annoyed them with my perceived flippancy .

On January 12, 1971, I received a letter in the mail from Dr. Paul Schmidt, head of the Graduate Division (who I always called “Dad” because of our identical last names), which said that the Graduate Council had read the description of my proposed project, and accepted it. At the bottom of the letter he had included the written comments of the other council members. One teacher said, “If this is acceptable as a project description, then I wonder why we require it at all." Another said, “Fine.” Another, “Good luck.” And the final word was, “Best wishes for working it out.

TOMBSTONE (1970)

Some of my last moments as a sculptor came in the early days of graduate school, when I was finishing up a large white bronze casting about as tall and almost as skinny as a surfboard, its six-foot-high base leading into two wings about three feet high, whose feathery tips knotted together at the top. It was while I was on the CCAC campus getting help from sculptor Don Rich, who was welding the wings casting to its base, that I almost passed up the path to making movies.

A fellow student walked up to me asking about the special video class I’d been invited to attend. He said that the teacher, Phil Makanna, told him the class was full, but suggested he check around to see if there would be anyone dropping out. The student wondered if he could take my place. In a weak moment I said sure, he could have my seat.

He seemed very happy as he turned and quickly walked away, probably heading directly toward the video lab across campus. His eagerness gave me a moment of doubt. Had I done the right thing for myself, I quickly wondered? Or was I making a bad mistake? Before he got more than twenty feet down the path I called out his name. He turned around. I said, “On second thought, I’d better keep the class. I’ve changed my mind.” I know part of me had wanted to avoid the whole idea of video. After all, who would want to be around hot lights and cameras that scrutinized one’s every move? But another side of me was busy exploring any and all new frontiers, pushing the envelope. Why I changed my mind I still don’t fully understand, but that seemingly small decision set me on my way into video, film, and eventually led to writing my book, Feature Filmmaking at Used-Car Prices and producing/directing (scripting/improving, shooting/editing/paying for…) over 25 feature-length movies Did I change my decision to take the video class because of a tiny whisper in my ear (like the voice that said, “Don’t over-correct,” when my car was skidding off Highway 101 at 120 miles per hour (see UNLEASING THE HORSES)? Some thoughts are just like a whisper.

————

Nice…Yep...sounds to me like muses of video/film were more than happy to change your mind and glad they did.

Wow!! Great stories! Love this: "Probably the most insane part about those days was that I was making up my own rules in life and they were working!" Plus you had that voice in your ear . . .