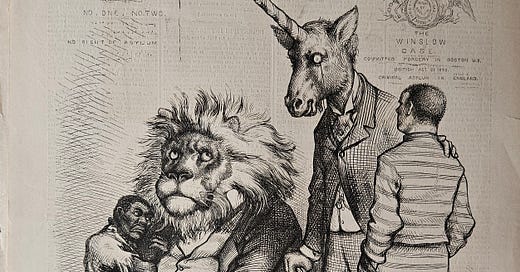

"The Lion and Unicorn, Fighting (again!)", June 17, 1876. (SOME AMAZING animal characterizations by Thomas Nast, Harper's Weekly (some symbols from UK...)

https://offbeatunicorn.com/2019/02/12/the-lion-and-the-unicorn-fighting-again/

"The Lion and Unicorn, Fighting (again!)" by Thomas Nast.

(The unicorn is the conservative, pro-national and pro-imperial Disraeli, and the bespectacled lion is the liberal, reform-oriented Gladstone).

————

(Writeup/descriptions from OFF-BEAT UNICORN

On first look, this is rather weird, since the cartoon is from ten years after the American Civil War. But, if you look closely, you’ll see that this has to do with the UK-US extradition treaty case of Ezra D. Winslow in 1876. Leonine Gladstone and Unicorn Disraeli were famous political rivals. In 1876, Disraeli was Prime Minister and Gladstone was the leader of the Liberal opposition. The bug-eyed Unicorn Disraeli seems rather surprised that the lion is bringing up past unpleasantness (to put it mildly).

Neither were what we would call progressives when it came to American slavery, and though slavery was termed illegal in England in the 1772 Somersett case, and the trade ended in 1807, slavery was only abolished in the British empire in 1833. Gladstone’s reputation as a liberalizer had to do with widening (normatively white male) voting rights. So it’s a little surprising to see American cartoonists aligning him with the protection of fugitive slaves.

Anyways, it’s clear that through the nineteenth century, the lion and the unicorn symbolize robust debate about what unites – and divides – the United Kingdom.

More recently, in 2016, The Telegraph ran a pro-Brexit cartoon of the lion and unicorn running together away from the European Union.

(Go to https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/06/23/wewantout—tell-us-why-you-hope-leave-will-win-the-eu-referendu1/ to read the article. Hindsight stings, eh?)

Ironically, when the lion and unicorn aren’t fighting over the terms of a “United” Kingdom, disaster follows. In 2019, the Economist ran a cartoon of Theresa May riding a unicorn, with no lion in sight. And that was a testament not to the UK’s power, but to its delusions of an easy path back to independent greatness and the fantastical quality of May’s ability to hold onto her position as prime minister. The lion, once a symbol of expansion, then of stay-at-home Englishness, has disappeared entirely. Instead, we have the delusional unicorn leading Britain west, away from Continental Europe.

So, the Lion and the Unicorn are famous emblems of Great Britain, but they are not peaceful or cooperative ones. The dominating, kingly lion has been part of English royal heraldry since the medieval Plantagenets, but the feisty unicorn was the symbol of resistant, rebellious Scotland. If Scotland became part of England during the 1707 Act of Union, it wasn’t to please the Scottish. (They had rebellions in 1715 and 1745, and though the independence referendum of 2014 narrowly failed, Brexit is testing that union once more.) Therefore, the lion and the unicorn might equally be holding up the crown together…or wrestling for it.

The tension between the lion and unicorn is so ingrained that there’s a nursery rhyme about it. Lewis Carroll’s Alice cites “the old song” in Through the Looking-Glass:

The Lion and the Unicorn were fighting for the crown:

The Lion beat the Unicorn all round the town.

Some gave them white bread, some gave them brown:

Some gave them plum-cake and drummed them out of town

The lion and the unicorn come, over the years, to represent the two main political party leaders. In the 1853 Punch cartoon, the unicorn is the conservative, pro-national and pro-imperial Disraeli and the bespectacled lion is the liberal, reform-oriented Gladstone. This signals a weird inversion of the lion and unicorn’s original affiliations. While the English lion once dominated the independent-minded Scottish unicorn, now it is the unicorn who waves the Union Jack and bears a warlike shield.

llustration to “The British Lion” in Punch (Jan-June 1853). For more, see Michael Hancher’s “Punch and Alice” in Lewis Carroll: A Celebration. Ed. E Guiliano, New York, 1982. Or go to the useful site where I found the image: http://www.alice-in-wonderland.net/resources/analysis/picture-origins/

In a meta method appropriate to Wonderland, Tenniel satirizes the satire. Eighteen years after the original cartoon, in Through the Looking-Glass (1871), the unicorn sports a Union Jack suit (that is also Elizabethan) and sports Disraeli’s equine nose. The lion is even more worn-out, sporting Gladstone’s glasses. He’s also deprived of any clothing. Being a stay-at-home lion no longer seems so attractive.

Tenniel, John. “The Lion and the Unicorn.” Through the Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll. 1871. London: Penguin, 1998. 202.

When people stop believing in the lion and stop fearing the unicorn, Narnia collapses. C.S. Lewis wasn’t working in a vacuum and the threat to the lion and unicorn isn’t just about a threat to Narnia, but also a threat to Great Britain, whom lions and unicorns traditionally represent. (To see just how present the lion and unicorn iconography is, check out the coat of arms in the top left hand corner of Queen Elizabeth’s website: https://www.royal.uk/her-majesty-the-queen)

————

Thanks, Rick, for these luminous threads of history. Most definitely symbols have guided us since we learned how to scratch images in the sand.

Admiring, again, the unimaginable skill and intense and lengthy concentration and focus required to do this work! (And playing around with the imagery of the animals chosen to represent political / philosophical differences: Lion / Unicorn and Elephant / Donkey.)