OUIJA BOARD (1978)

Sometime around this period (1978) I bought a Ouija Board at a garage sale and stuck it in my closet. I thought it might be a good prop at some point. But Heather, (then 11) and Morgan (9) discovered it, dug it out, and began actively using it while I rested, trying to recover from the latest disappointments and exhaustion. By the time I realized how attached they were becoming to the game, they had spent a considerable amount of time talking to “the spirit” or whatever moved their hands rapidly all over the board.

They even had a name for the entity that they conversed with (a tidbit I don’t seem to remember – just a bunch of numbers). As I watched the procedure, heard the dialogue between my kids and this stupid board, I started getting a little nervous. Did this thing really work? Was it possible that they had actually made contact with something? They were too young to really know much beyond the fact that it was fun for them. But to me it was real spooky. But before I threw the thing out, I decided to run a little test.

I told my kids to do me a favor, and ask “their friend” to spell out the initials of the film company that was bothering me with legal problems. Within the blink of an eye, a delighted Heather and Morgan took their places at the Ouija Board, placing their fingertips on its triangle-shaped plastic pointer. I watched in disbelief as it sped right over to the “M”, hesitated, then moved from there to “G,” held another instant, and finally glided straight back to “M.” There was no way that they could have known this “MGM” information! I immediately packed it up, put it on the highest shelf, and threw it into a dumpster the next day.

OLD DODGE EPILOGUE (1979)

After a decade of continued use, it finally came time to cash in my old 1939 Dodge pickup so I could force the production of a third feature. Although I had been exceedingly lucky that my film 1988-The Remake had won me another NEA grant, this time for $7,500 to shoot Emerald Cities (the final feature of my trilogy with actors Dick, Ed and Z), most of that money was quickly spent clearing the lab bill at Palmer Lab again. And I still had to produce the film. The truck was the only disposable asset I had. I figured that I needed a budget of around $4,000 to shoot the opening scenes in DeathValley,California. It would cost that much for filmstock (10 400’ rolls) and processing, the rental of a camera, a sound person to record sync dialogue on location, the transportation, gas money, housing, and food for eight people (four actors and four technicians). So in a moment of utter desperation I put a “For Sale” sign in the little back window of the truck, and less than a week later a guy who owned a Mexican restaurant in downtown Oakland called to see it. After a cursory inspection, he agreed to pay me $1200. Maybe it was the recently installed blue leather seat covers (that cost me $300) that did it. The interior certainly looked mint at the time.

It was a sorrowful day when I was left holding a little pile of one hundred dollar bills as my precious truck rolled away with someone else in the driver’s seat. But a part of me did feel relief at finding it a good home, selling it to someone who had a good cash flow for future repairs. I had known for a while that if the engine ever blew on me I would have been helpless to bring it back to life. A decade had gone by, ten years since I’d been homeless after the separation from my first wife and had stumbled upon the truck one fateful summer afternoon in 1969 (ENERGY FROM THE GROUND). I couldn’t help wondering if the original owner, a nice older gentleman, was still alive, still living in his cottage because he couldn’t afford the taxes on the big front house. I had driven friends by my truck’s original garage, to show where it had “been born,” but never had made the time to just stop by and pay a visit. What had happened to my ability to live in the present? I certainly didn’t have much patience anymore, like the ability to chat with someone long enough to hear about their old truck.

For most of the time I drove it, my ’39 Dodge had been trouble-free. It had never quit on me on those many trips over the Bay Bridge to edit at Palmer's, kept me rolling through two feature film productions and carting around my precious cargo of young kids. It had been a lovely collaboration.

The little-truck-that-could had pulled me through with flying colors. So...goodbye. But exchanging my truck for movie money didn’t raise the full budget. I needed at least two thousand more, I suddenly realized. And I got real crazy then, knowing that if I didn’t snap myself into gear, raise more money and recruit people in earnest, that sacrifice would have been for naught. I was tremendously angst-ridden then, angry at myself for being so stupid, just sick at heart. My great truck gone. And I had no movie, either .

One night, right after the upsetting sale, I dreamed of talking to my friend Nick Bertoni about making the movie. When I awoke the next morning, I remembered that Nick had offered in the dream to loan me a thousand dollars and do on-location sound. I called his house after breakfast and, amazingly, he did agree to help with the cash, adding that if he could get his hands on the Mills college Nagra recorder (and check it out over the Christmas vacation), he’d also be my soundman. The ball was suddenly rolling!

In my aggressive desperation, I kept making the necessary phone calls. I was able to convince another friend, Bill Kimberlin (author of INSIDE THE STAR WAR EMPIRE, A MEMOIR, to rent me his 16MM camera (half down). With his insistence on accompanying the camera on location, I automatically got myself a cinematographer as well. Then Ed loaned me something like $500, and offered his large jeep station wagon for transportation. Carolyn Zaremba agreed to star, actors Kelly Boen and Ted Falconi (a Flipper band member) jumped aboard, and Julie offered to shoot stills and be my assistant. Finally, Palmer lab agreed to let me charge the ten rolls of filmstock and processing. Suddenly, we were all set. I had terrorized myself so thoroughly by selling my beautiful Dodge that I was able to generate the five- day shoot, filming around Trona, Death Valley, just before Christmas, 1979.

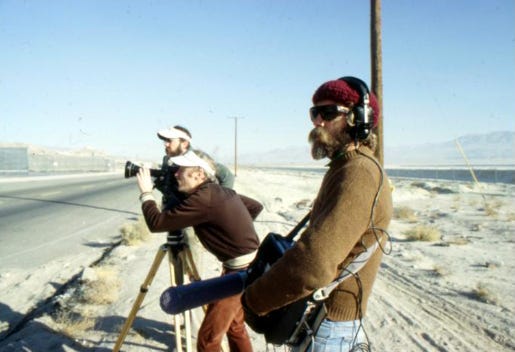

BILL KIMBERLIN LINES UP SHOT (I’M BEHIND HIM), and NICK BERTONI-LOCATION SOUND RECORDIST, Emerald Cities shoot, Trona, Death Valley, 1979.

TV SALE (1980)

In the fall of 1980 the London Film Festival decided to present my censored feature, 1988-The Remake, as part of their first Independent American Film section, and I traveled to England with my wife Julie to take advantage of their hospitality and perform the duties of an in-person filmmaker. I introduced my film and answered questions afterwards, sharing the stage with filmmaker friend Jon Jost, who had arranged for a four-stop film tour of showcases in England and Wales afterward, to screen our work and pick up some extra cash.

To my utter surprise I found the London festival audiences packed and myself in demand for radio interviews, all as a result of having a still from the film selected to represent the twenty or so American independent features covered in The Guardian newspaper article. Most likely the picture of a drag queen named Billy, from the Showboat audition, was chosen because he looked so similar to May West, whose photo also adorned The Guardian page due to her untimely death. They were both sporting almost identical black slips and dyed hair. At any rate, because of this fluky coincidence, it seemed to be my turn for luck and good fortune.

My first London radio interview almost didn't happen, due to traffic jams. Arriving late at London Radio (a super-station) for the early morning show, I was told by the host that we’d have to cancel because we hadn’t had time to review the topics. In my crazy jet-lagged state I just blurted out, “I can do it cold!” He stared at me for a second and then said, “OK, Let’s go!”

A minute later I was on the air, live, reaching an estimated audience of over a million people on their way to work. Right after the broadcast another radio station, Capital Radio, called over to get me on their show. I was knocking off ducks in a row!

And even more good things happened. I was introduced to a TV buyer Derek Hill, for the new Channel 4 TV in London, resulting in a lifesaving sale ($13,000). For once everything had gone my way. When I got a letter from Mr. Hill after the film was broadcast in 1982, I was thrilled to learn that it had gone out to an audience of 350,000 viewers, in the prime-time 11PM Friday night slot. Thinking about that huge television audience, as compared to the small audiences for my sculptures, I realized why I had switched allegiance to video and film during my graduate studies at The California College of Arts in the early 1970s. Because my film was broadcast into so many homes, it was actually possible that it might make a change in somebody’s life. Maybe by watching Ed Nylund’s real-life story unfold, then seeing him and the auditioners throw off their constraints, risk all for their dream, a few more people would be encouraged to, as author Joseph Campbell put it, follow their bliss.

Adding up the total amount of time all those people in England watched 1988-THE REMAKE (yes, they saw the censored version, with all its beeps, honks, and silent subtitled songs), 350,000 people times 93 minutes, I figured out that my film had been watched for the equivalent of 22,604 days, or over 60-years-worth of viewing time. Maybe it was worth all the suffering and struggle it took to be a filmmaker .

–––––––––

Share this post