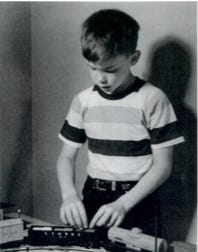

Real-Life Stories #3––born "breech," cherries OD, my 4-tine garden fork, Cowlick, etc. (age 1-9).

My early stories before the blue toilet fire: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/35987705-twelve-dead-frogs-and-other-stories-a-filmmaker-s-memoir?from_search=true&from_srp=true&qid=Aqd2jVCwwx&rank=1

PAIN FROM THE MOTHER (BIRTH REENACTMENT)

DEAD RATTLER

SENTENCES

RED DEATH

A LITTLE INDIAN

PLAYING DANGEROUS GAMES

SILVER PITCHFORK

COWLICK

———————

PAIN FROM THE MOTHER (1944)

When I told a half-Cherokee sculptor friend of mine in Oakland that I had been born “breech,” arm and leg first, he said that I would have been considered a sage or shaman to Native American tribes, because I had ’taken the pain from the mother.’ He said that since I had begun life with a life-or-death struggle, I would have earned the right to be treated specially by my tribe. We’ve all seen movies where Indians are dangled at the end of ropes threaded through their chests, conducting their self-imposed torture during the Sioux Sun Dance ceremony. I wonder how my birth stacked up against that level of pain. Somewhere, locked deep in my sub-consciousness, the memory of my birth still exists – prodding forceps clamping down, twisting and turning me, followed by extraction from my mother’s uterus into the harsh glare of an operating room. What was it really like?

BIRTH REENACTMENT (1944)

At seven months, I am floating around in my mother’s amniotic fluids, still head-up, nowhere near the correct position for normal birth, where the head descends, to lead the baby out the birth canal. Suddenly my mother’s body signals that she is having a premature birth and she is rushed to the hospital. Within minutes she is tranquilized into unconsciousness and rolled by gurney into a delivery room. Her doctor has been called off the golf course and dons his surgeon’s greens, washing his hands while joking with the nurse in attendance about ’the bogey on hole seven.’ Snap, snap, the rubber gloves are secured over his hands. Looking back for a second at the young nurse to laugh at her witty remark – something about how he’ll need to use a nine-iron to scoop me out – he enters the room.

As I’ve said, my young mother, age 28, is out cold. So no chitchat is necessary, no bedside manner for the doctor to worry about. He goes to work, running his hands over her stomach like an auto body repairman sizing up the dent in a Chevy. Yes, there’s some work to be done here, he thinks to himself.

First he makes an incision to open up the vagina as wide as possible (he needs some elbow room there), and goes in with the fingers. It doesn’t take long to confirm that my legs and an arm are down there, near the opening. Inside, I feel the invasion and try to retract my appendages away from the intruder. Finally the probing stops and my heart beat returns to normal. Then comes the metal forceps. With great dexterity the doctor eases the metal jaws into the birth canal and grabs hold of my leg. Ouch! I feel the pain and I contort, furiously kicking at the grip. But it won’t let go. Suddenly I’m being rotated, and there’s nothing I can do about it. Outside in the bright lights of the operating room, the doctor narrates his actions like he’s still out on the fairway – he says it helps both the deliveries and his golf score.

“Driving it home. Yep. Seeing the clubhouse up ahead now.”

Finally the doctor has re-positioned my torso, preparing to drop my head into position. The vise-grip releases, temporarily. I recover, my jaw closing slightly as my silent scream abates. Then a horrible sensation shocks my skull, as the metal monster latches on. My heart races spasmodically as the pain increases. I feel my face squashing in, eyes popping, ears flattened by the unforgiving claws. I’m dragged, down, down. The doctor, who is an all-around sportsman, now resorts to fishing terms more suited for the finale.

“Reeling in a big one–still got some fight, but think I can land ’em.”

My eyes are being squeezed together, forced open through their lids, but I’m still in darkness. Suddenly, at the threshold of pain I emerge, jerked out into the blinding light. The forceps are removed from the sides of my head and I cry furiously while nurses comment on my small size (5 pounds) and condition (black and blue).

As the doctor receives his well-deserved accolades, takes a bow or two, he can’t help recounting the landing of an 80-pounder off the shore of St. Johns the previous month. At any rate, I’m born alive, in Chicago, Illinois, during the latter part of WWII.

For a Native American baby who experienced such a breech birth, encamped with his family somewhere on the plains (Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska?), he or she would have been at much greater risk of stillbirth. With no sterile environment, no monitoring devices, no incubator or modern medicines (NO forceps for extraction…), what was his or her life expectancy?

DEAD RATTLER (1945)

When I was one-and-a-half years old, we moved to a small house just outside of Phoenix, Arizona for the winter, sparing my father the harsh Chicago weather that exacerbated his pulmonary problems (symptoms of emphysema were forthcoming). My mother said that when I saw some kids my size approaching I became scared, wondering what they were. I thought the entire world was made up of just one small person (me), the rest parent-size.

Sand storms more than once gave our house a thorough dusting – fun cleanup for a housewife, mom said. And we were plagued with typical desert dwellers. To protect me from an infestation of scorpions, my father placed each foot of my crib into a bucket of water, but my mother said she did find one on the wall next to where I was sleeping.

One morning I was sitting alone in my sandbox in our desert back yard when a six-foot rattlesnake headed over. When it was a few feet from where I was playing, within striking distance, our German Shepherd pounced on it and tore it apart. This was before TV, where every parent learns to be overly cautious from talk shows.

SENTENCES (1946)

I do think I remember saying my first word, “screwdriver,” at about age two-and-a-half, outside the front gate of my great-grandmother’s Victorian house in the Midwest. Of course I can’t be sure. But my mind still holds an image of talking to some workman near the entrance to the property. It’s hard to determine if the stories we recount from our childhood are real, but I do seem to remember everyone being tremendously excited when I finally talked.

RED DEATH (1946)

My mother said that one of the biggest scares she had during my infancy was when I was around two-and-a-half years old. She found me vomiting red liquid, sitting there on the floor of the pantry. I had discovered a jar of maraschino cherries stored in a low cabinet and had eaten half of the contents. It took awhile, she said, to recover from finding her baby in a pool of blood.

A LITTLE INDIAN (1948)

It’s ironic that I could never ’sit like a little Indian’ at play-school, kindergarten or later (still can’t), given the ’Shaman’ aspect of my breech birth. Obviously my joints were too traumatized during my difficult birth to allow the flexibility needed to sit cross-legged. I have a breech baby friend who has this same problem, so it’s probably not uncommon. At any rate, from the very first moments of school, I felt like an outsider.

PLAYING DANGEROUS GAMES (1949)

At some point during pre-kindergarten playschool, my parents were brought in for a special meeting. The teachers had complained that I made up dangerous games in which all the other kids participated. They were asked if they could please talk to me about stopping this bad behavior. I guess they did, because I certainly didn’t try to exercise any form of leadership qualities for the next twenty years, until I began convincing people to jump off bridges to help me make movies.

SILVER PITCHFORK (1952)

Around this time, I walked to a nearby hardware store about seven or eight blocks away (can eight-year-olds still walk a mile by themselves on the South Side of Chicago?) and spent all of my savings – around $6 – on a beautiful, silver-and- blue-painted spade garden fork (like a pitchfork, but with just four thicker tines). I have no idea why I bought it, or what I thought I’d do with it once I got it home (we had no garden). But I do remember loving it, and being extremely proud of my purchase. Maybe it’s a clue to my past life as a farmer in Illinois or somewhere. That’s the only explanation I can offer.

COWLICK (1953)

One interaction with my father that I remember clearly was when he took me to get a haircut when I was nine old. I was sitting in the barber’s chair, hoisted up and spun around to where I was facing the mirror, while he and the barber had an argument over where to part my hair. The barber was adamant that my hair should be parted on the left side, while I preferred the right, where it naturally fell. It developed into a real battle of the wills. He explained that for me to be “normal,” I’d need to have my hair parted on the left. Left side...like everybody else.

But I had a cowlick that resisted that arrangement. The barber wouldn’t back down, though. He kept insisting that it my hair be parted “correctly.” My father stuck by me, all the way on this, telling the barber to just do whatever I wanted. The barber’s last words before reluctantly giving in, were, “OK, but he’ll never fit into society .”

I tell this Cowlick story in my third feature, a “punk/Christmas” movie, EMERALD CITIES (with bands FLIPPER, and THE MUTANTS): https://mubi.com/en/us/films/emerald-cities

To read my book about writing/directing EMERALD CITIES, click here: https://diyfilmmaker.blogspot.com/2020/08/new-rick-schmidt-book-new-dark-ages-how.html