My LAST MOMENTS AS A SCULPTOR/almost missed taking a video class from Phil Makanna/CCA got me making movies/writing books, & showing 'real-life fiction' on the silver..er..ah.(computer) screens.

https://www.thriftbooks.com/w/twelve-dead-frogs-and-other-stories-a-filmmakers-memoir_rick-schmidt/28299073/item/60981149/?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=shopping_new_condition_books_hi

Stories excerpted from TWELVE DEAD FROGS, A Filmmaker’s Memoir.

———-

TOMBSTONE (1970)

Some of my last moments as a sculptor came in the early days of graduate school, when I was finishing up a large white bronze casting about as tall and almost as skinny as a surfboard, its six-foot-high base leading into two wings about three feet high, whose feathery tips knotted together at the top. It was while I was on the CCAC campus getting help from sculptor Don Rich, who was welding the wings casting to its base, that I almost passed up the path to making movies.

A fellow student walked up to me asking about the special video class I’d been invited to attend. He said that the teacher, Phil Makanna, told him the class was full, but suggested he check around to see if there would be anyone dropping out. The student wondered if he could take my place. In a weak moment—being distracted in the middle of finishing my sculpture, not yet knowing it would be my last) I said sure, he could have my seat.

He seemed very happy as he turned and quickly walked away, probably heading directly toward the video lab across campus. His eagerness gave me a moment of doubt. Had I done the right thing for myself, I quickly wondered? Or was I making a bad mistake? Before he got more than twenty feet down the path I called out his name. He turned around. I said, “On second thought, I’d better keep the class. I’ve changed my mind.” I know part of me had wanted to avoid the whole idea of video. After all, who would want to be around hot lights and cameras that scrutinized one’s every move? But another side of me was busy exploring any and all new frontiers, pushing the envelope.

Why I changed my mind I still don’t fully understand, but that seemingly small decision set me on my way into video, filmmaking, and eventually led to my book, Feature Filmmaking at Used-Car Prices. Did I change my decision to take the video class because of a tiny whisper in my ear (like the voice that said, “Don’t over-correct,” when my car was skidding off Highway 101 at 125 miles per hour?). Some important thoughts are just like a whisper.

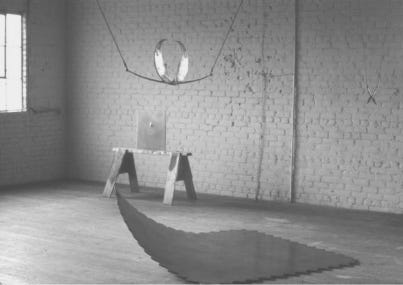

MY LAST SCULPTURE SHOW (A FEW PIECES OUT OF TWO MORE ROOMS-FULL), EAST OAKLAND STUDIO, 1970.

I heard later that one of Charlie Simonds’ sculpture students at University of California at Turlock where he was then teaching was looking for scrap bronze, so I sold him my winged bronze tombstone by the weight. I just wasn’t so object-oriented that period that I enjoyed risking a hernia moving the heavy thing around the studio, storing it or whatever. About six months later Charlie informed me that the student didn’t melt it down, but decided he liked it as art, had spared it from the blast furnace. If you’re ever in Turlock and see a pair of glistening white metal knotted wings, jutting skyward over the top of the next-door neighbor’s fence (or standing among a bunch of stone markers in a nearby graveyard), you’ll know what happened to the only sculpture of mine that ever got away.

PART 5***** FILMMATIC FUSION

FIRST VIDEO (1970)

After I signed up for Phil Makanna’s video class, I just jumped in wholeheartedly, like I had with sculpture. The first assignment was to take the portable video camera home for the weekend and shoot a movie. I decided to interview my ex-wife Mary-Ann. Arriving at her house on a Saturday, I placed her in a well-lighted spot near a window, pushed the "on" button, made sure that the reel-to- reel video tape recorder was rolling, and then began by asking her the crucial question, “What went wrong?” For twenty minutes (the length of the video tape) we had a conversation, her speaking on camera, me talking from behind the eyepiece.

The following Monday I showed the footage to the class, and they had a powerful response. Everyone had their hands on some part of their face, elbows up on legs supporting chins, eyes glazed, the room silent except for the hum of the playback machine. The dialogue between me and my ex-wife revealed all too clearly (and painfully) why we broke up. I learned later, as I got to know my fellow classmates, that four out of the seven members were divorced ex-husbands just like me.

THE LEGAL OPERATION (1971)

The first time I used actors was in a video entitled The Legal Operation. I had driven by my girlfriend Linda’s house but she wasn’t there, so I convinced her sister Jane (just a year younger) to be in my movie. I really had no plan about what to film, but had brought along my audio tape recorder so I could make up some dialogue on the fly, maybe play it back while the video camera was running. I just thought it might be cool to put her in some kind of old, dilapidated environment, where I could get some good shots.

In downtown Oakland, I found a nice stretch of three Victorian-era houses in the process of being demolished and asked one of the neighboring storekeepers if he knew how I could get into the buildings. He made a quick call, then told me for $5 he’d let me in. As he pulled out a large lock cutter from behind his old cluttered desk, he explained that the front door was padlocked from the outside, but I could, “Just cut’r off.” Seeing those cutters gave me a familiar twinge, being identical to the ones I had used in the foundry a year before to get late-night access to the power tools cabinet at CCAC (see THE TEACHER’S CHAIR).

As Jane videotaped me, I cut the lock off in one try, that shot later edited into the title sequence of the short film. I then spoke into my audio recorder, repeating the words, “Don’t leave me. Please don’t leave me! I need you. Come back.” Because the recorder was running a little off-speed, my voice came out slightly slurred, poorly modulated, in other words, perfect for the shots we got. Inside the house I videotaped Jane peeling off wall paper with her hands, wandering around the rooms, walking up the old staircase and then circling the upper floor stairwell as she kept a hand on the railing, looking down at me. Since I was aiming the camera up at her and taking in the old leaded skylight above at the same time, her image looked silhouetted (and spooky) against the back-lighting. A close-up shot of her darkened face, hair shifting from side to side, cross members of skylight panes intersecting with her movement, was one of the most powerful images I’ve ever shot. By the time I had videotaped her sitting alone in one of the dilapidated rooms, kicking a broken old radio to the floor and shouting the word “Never,” she actually looked the part of a woman having an emotional breakdown.

A few days later, I checked out the video camera again and decided to shoot at the old Herrick Hospital in Oakland. What a scary place! While I was taping some of the hallways, trying to be inconspicuous, a doctor walked into the shot. He asked me what I was doing (Busted, I thought!). I explained that I was making a movie and to my shock he offered to help, even act in it! He escorted me down to the basement floor morgue. I got a great shot through the crisscross metal gate of the ancient elevator as we descended (to the underworld from all appearances…), where I videotaped a dead person’s toe with a tag on it (frightening!), and recorded the doctor in an old operating room, just running his hands back and forth over the cleanly starched sheets on the metal bed, saying, “Everything will be OK, Jane, you’re really improving. Your treatment’s going well. You’re getting better.”

The next day I brought Jane to the hospital and videotaped the doctor dragging her down a hallway, until they both finally disappeared around a corner. The strange neon lighting, reflective floors, and general sterility of that man-made tunnel was the perfect look for the film’s ending.

When I showed teacher Phil Makanna all my strange footage he flipped out, saying, “You have to edit!” But CCAC didn’t have any video editing equipment at the time (and neither did hardly anyone else, since these were the first Sony 1/2” machines in America). So he convinced me to transfer the results to 16MM film and cut it that way. I took my videotape rolls to W.A. Palmer Films, then in San Francisco, California, and learned that Bill Palmer, the owner of the company, had invented the kinescope machine used for such video-to-film transfers. Mr. Palmer told me that I needed something called a double system transfer, that supplied me with a film original, work print, and a separate sound track so I could edit sound and picture freely on the work print, and then use the original rolls to make a final composite Answer print. “Sure, OK, fine, whatever you think is best,” I said, not knowing anything at all about filmmaking. I was just honored that Bill Palmer himself would assist with the transfers.

It was soon after that that I was granted my first financial miracle of filmmaking. The cashier at Palmer Films, a lovely older blond-haired woman named Lois, agreed to extend me credit! Her son, George, also worked at Palmers (he later did sound mixes on several of my features), so maybe she just favored young people. It was obvious that she enjoyed helping me out. Thanks to her I was able to charge the $700 for the video-to-film transfers and start cutting.

Since I knew nothing about film editing, I asked the Palmer employee who arranged the editing room rentals if he would show me how to make a splice. Because he knew that I was renting an editing cubicle usually reserved for “conforming” (matching original scenes to the workprint copy, and splicing them together in a checkerboard pattern for printing), he instructed me in the delicate art of hot-splicing. It didn’t surprise me to see the splicer chop off a picture frame each time he clamped down the lid after glue was applied to the film ends. I didn’t know about tape splicers, which allowed for cutting and reassembly without frame loss. Using a moviescope for viewing picture workprint, and a sound reader to hear the soundtrack as it passed over sound heads connected to a tiny speaker, I synced up my shots by lining up the three white frames at the head end of each shot and the corresponding three beeps on the track. My syncronizing block held the picture and soundtrack rolls temporarily together as I reeled up to the next shot. Once all the shots were synced up I started having fun, cutting off leaders, shortening shots, rearranging the order of events.

Every evening, after Palmer Films closed, I carried my rolls of workprint and mag to the front screening room and asked the young, after-hours technician (Bill Kimberlin––he became a chief editor at LucasFilm, and writer/director of the highly successful drag racing classic, American Nitro), who was busy transferring mag track to optical sound for prints, if he could project my work-in-progress. When questioned as to whether or not I had authorization for the free screening, I told him it was my understanding that I could screen my cuts while I rented the editing cubicle. So with him often sitting in, I was able to see my cut improve. Each new day I attacked the footage, applying what I learned from the previous night’s screening. With each hot splice the workprint shrank, as I discarded the outs into a waste basket.

PS. I doubt now, these 50+ years later, that I was actually given screening time in the $185/hr. “mixing” projection theatre there. But an important misunderstanding on my part!!

On that first little film (it ended up running about 14 minutes), I had it cut so tightly that the beginning shots of “Rick and bolt cutters,” and “Rick runs upstairs,” had a series of three frame cuts, all neatly glued together. About five days later, when I had just about wrapped up my editing, I discovered that I had been mistaken about the free screenings, learning that nobody had ever used the expensive Studio-1 screening room ($80 per hour!) for anything but expensive sound mixing and final projections of finished prints.

When I let Phil know that I had completed the editing, he arranged a special screening at Channel 9/KQED in San Francisco where he had recently collaborated to create one of the first experimental videos funded by the noted Dilixi Foundation. While the little audience congregated, Phil motioned me toward the interlock projector, but I quickly let him know I didn’t know how to thread it. With a confused look, he took hold of my sync picture and sound rolls and said he’d do it for me. He must have wondered how I could have edited a film without ever threading it on a projector.

As he began unwinding the head footage to thread up, he suddenly turned to me in shock, asking if I had hot-spliced the entire picture roll. I said, “Yes.” As he ran his fingers along the edge of the three-frame long sequence at the beginning of the picture roll, he couldn’t believe it. When he asked how had I had been so sure of my cut, enough to make such permanent splices, I didn’t know what he was talking about.

With a disoriented look on his face Phil finished threading up my footage, called for the projection room’s lights to be lowered, and clicked on the projector. It was an exciting and frightening experience to see the results of my labor finally running as a real movie before an audience of strangers (Phil had pulled in editors, producers, directors, and administrators from Channel 9 for the screening). Fortunately, the film seemed to work. I was given compliments afterwards, and offered free titling by the TV station manager. Later, when it came time to complete the film, Phil connected me up to his professional negative cutter, Lela Smith, who conformed my original 16MM footage (from the kinescope) so the film could be printed at W.A. Palmer Lab. I didn’t find out until much later that she was the special editor for poet James Broughton, and other famous “beats.” And was surprised when I learned he and partner Joel Singer lived just a few miles away in my new town of Port Townsend, WA). In any case, thanks to Philip Makanna, I had been fully bitten by the filmmaking bug.

———-

Wonderful reminiscenses, Rick, of wobbling through those early days of art school, that grand marriage of the unpredictable. And here we are, still futzing with the mystery!

Alchemy! There's something about KNOWING where you want to go that lines things up to get you there.