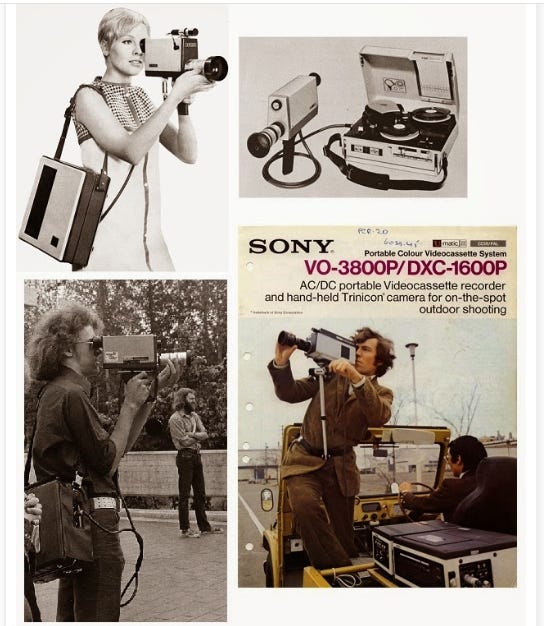

My introduction to 'FILM-MAKING' (1970)--using one of the first portable video cameras in the US-Sony's PortaPak w/recorder. How I got BITTEN by the filmmaking bug!

"12 DEAD FROGS" memoir in paperback): https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0777FHXX2

(Excerpted from TWELVE DEAD FROGS AND OTHER STORIES, A Filmmaker’s Memoir, by Rick Schmidt ©2017).

PART 5

***** FILMMATIC FUSION

FIRST VIDEO (1970)

After I signed up for Phil Makanna’s video class, I just jumped in wholeheartedly, like I had with sculpture. The first assignment was to take the portable video camera home for the weekend and shoot a movie. I decided to do an interview wit my ex-wife. Arriving at her house on a Saturday, I placed her in a well-lighted spot near a window, pushed the "on" button, made sure that the reel-to- reel video tape recorder was rolling, and then began by asking her the crucial question, “What went wrong?” For twenty minutes (the length of the video tape) we had a conversation, her speaking on camera, me talking from behind the eyepiece.

The following Monday I showed the footage to the class, and they had a powerful response. Everyone had their hands on some part of their face, elbows up on legs supporting chins, eyes glazed, the room silent except for the hum of the playback machine. The dialogue between me and my ex-wife revealed all too clearly (and painfully) why we broke up. I learned later, as I got to know my fellow classmates, that four out of the seven members were divorced ex-husbands just like myslf.

THE LEGAL OPERATION (1971)

The first time I used actors was in a video entitled The Legal Operation. I had driven by my girlfriend Linda’s house but she wasn’t there, so I convinced her sister Jane (just a year younger) to be in my movie. I really had no plan about what to film, but had brought along my audio tape recorder so I could make up some dialogue on the fly, maybe play it back while the video camera was running. I just thought it might be cool to put her in some kind of old, dilapidated environment, where I could get some good shots.

In downtown Oakland, I found a nice stretch of three Victorian-era houses in the process of being demolished and asked one of the neighboring storekeepers if he knew how I could get into the buildings. He made a quick call, then told me for $5 he’d let me in. As he pulled out a large lock cutter from behind his old cluttered desk, he explained that the front door was padlocked from the outside, but I could, “Just cut’r off.”

As Jane videotaped me, I cut the lock off in one try, that shot later edited into the title sequence of the short film. I then spoke into my audio recorder, repeating the words, “Don’t leave me. Please don’t leave me! I need you. Come back.” Because the recorder was running a little off-speed, my voice came out slightly slurred, poorly modulated, in other words, perfect for the shots we got.

When I showed teacher Phil Makanna all my strange footage he flipped out, saying, “You have to edit this!” But CCAC didn’t have any video editing equipment at the time, and neither did hardly anyone else, since these were the first Sony 1/2” machines in Americ). So he convinced me to transfer the results to 16MM film and cut it that way. I took my videotape rolls to W.A. Palmer Films, a full-services film lab in San Francisco, California, and learned that Bill Palmer, the owner of the company, had invented the kinescope machine used for such video-to-film transfers. Mr. Palmer told me that I needed something called a “double system transfer” that supplied me with a work print copy from my fim original, and a separate sound track so I could edit sound and picture freely, and then use the original rolls to make a final composite “Answer” print. OK, fine, whatever you think is best, I said, not knowing anything at all about filmmaking. I was just honored that Bill Palmer himself would assist with the video transfers.

It was soon after that that I was granted my first financial miracle of filmmaking. The cashier at Palmer Films, a lovely older blond-haired woman named Lois, agreed to extend me credit! Her son, George, also worked at Palmers (he later did sound mixes on several of my features), so maybe she just favored young people. It was obvious that she enjoyed helping me out. Thanks to her I was able to charge the $700––an amount double what CCAC charged for tuition and way beyond my budget––to cover the video-to-film transfers and start cutting.

https://talkingheadsconcerthistory.blogspot.com/2012/12/tape-talk-portapak.html

Since I knew nothing about film editing (had never taken a class in “film-making”), I asked the Palmer employee who arranged the editing room rentals if he would show me how to make a splice. Because he knew that I was renting an editing cubicle usually reserved for “conforming” (matching original scenes to the work print copy, and splicing them together in a checkerboard pattern later for printing), he instructed me in the delicate art of hot-splicing. It didn’t surprise me to see the splicer chop off a picture frame each time he clamped down the lid after glue was applied to the film ends. I didn’t know about tape splicers, which allowed for cutting and reassembly without frame loss. Using a moviescope for viewing picture workprint, and a sound reader to hear the soundtrack as it passed over sound heads connected to a tiny speaker, I synced up my shots by lining up the three white frames at the head end of each shot and the corresponding three beeps on the track. My “syncronizing block” kept the picture and soundtrack rolls temporarily clamped together as I reeled up to the next shot. Once all the shots were synced up I started having fun, cutting off leaders, shortening shots, rearranging the order of events.

Every evening, after Palmer Films closed, I carried my rolls of edited work print and synced mag soundtrack to the front screening room and asked the after-hours technician named Bill, who was busy transferring mag track to optical sound for prints, if he could project my work-in-progress. The young Bill Kimberlin would later become a friend who helped me shoot my movie, EMERALD CITIES, and write a best-seller about his next job at Lucasfilm, ‘Inside the Star Wars Empire.” When questioned as to whether or not I had authorization for the free screening, I told him it was my understanding was that I could screen my cuts while I rented the editing cubicle. So with him often sitting in, I was able to see my cut improve. Each new day I attacked the footage, applying what I learned from the previous night’s screening. With each hot splice the work print shrank as I discarded the outs into a waste basket.

On that first little film (it ended up running about 14 minutes), I had it cut so tightly that the beginning shots of “Rick and bolt cutters,” and “Rick runs up thew stairs,” had a series of three-frame cuts, all neatly glued together. About five days later, when I had just about wrapped up my editing, I discovered that I had been mistaken about the free screenings, learning that nobody had ever used the expensive Studio-1 screening room ($80 per hour!) for anything except expensive sound mixing and final projections of finished prints. How funny!

When I let Phil Makanna know that I had completed the editing as best I thought I could, he arranged a special screening at Channel 9/KQED in San Francisco where he had recently collaborated to create one of the first experimental videos funded by the noted Dilixi Foundation. While the little audience congregated, Phil motioned me toward the interlock projector, but I quickly let him know I didn’t know how to thread it. With a confused look, he took hold of my sync picture and sound rolls and said he’d do it for me. He must have wondered how I could have edited a film without ever threading it on a projector.

As he began unwinding the head footage to thread up, he suddenly turned to me in greater shock, asking if I had hot-spliced the entire picture roll. I said, Yes. As he ran his fingers along the edge of the three-frame long sequence at the beginning of the picture roll, he couldn’t believe it. When he asked how had I had been so sure of my cut, enough to make such permanent splices, I didn’t know what he was talking about.

With a disoriented look on his face Phil finished threading up my footage, called for the projection room’s lights to be lowered, and clicked on the projector. It was an exciting and frightening experience to see the results of my labor finally running as a real movie before an audience of strangers (Phil had pulled in editors, producers, directors, and administrators from Channel 9 for the screening). Fortunately, the film seemed to work. I was given compliments afterwards, and offered free titling by the TV station manager. Later, when it came time to complete the film, Phil connected me up to his professional negative cutter, Lela Smith, who edited many of poet/filmmaker James Broughton movies, to conform my original 16MM footage (from the kinescope) so the film could be printed at W.A. Palmer Lab. Thanks to California College of the Arts teacher Phil Makanna I had now been fully bitten by the filmmaking bug.

*****

More great stories! And your inclination to "make up the dialogue on the fly" was certainly prescient. Wow, so much fell into place as needed! (And, I loved the James Broughton reference. As you know, he lived across the driveway from us. Jessica took a film class that used his book and was able to go over and talk to him about it!)