MY Interview ABOUT MOVIEMAKING, by author/translator Bibbi Lee, "Nothing Grows by Moonlight," by Torborg Nedreaas (Penguin Classics, ©2025).

https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/465186/nothing-grows-by-moonlight-by-nedreaas-torborg/9780241729663

Interview excerpted from the book, SLEEPER TRILOGY––Three Undiscovered First Features by Rick Schmidt, 1973-1983.

—————

FILMMAKER RICK SCHMIDT INTERVIEWED BY AUTHOR/TRANSLATOR BIBBI LEE

Filmmaker Rick Schmidt lived with his wife Julie and young son Marlon, in an old Victorian house on the side of a hill overlooking Point Richmond, California. This little town's two block long main street nestles invisibly along the highway, and most travelers would be unaware of its existence unless they made a wrong turn. A block above Schmidt's house one can see an extraordinary view of the Bay Area, from the Golden Gate Bridge to the protruding spike of the Transamerica building in downtown San Francisco. I see it as an apt metaphor that Schmidt exists invisibly at the edge of this sprawling metropolis, just as his three feature films A MAN, A WOMAN, AND A KILLER (co-directed by Wayne Wang), (SHOWBOAT) 1988-THE REMAKE, and EMERALD CITIES remain unknown to all but a few of the most knowledgeable film historians.

UPDATE: Schmidt still lives invisibly with his wife Julie, but currently resides (2022) in a small New Mexican village outside of sprawling Santa Fe. And he's still relatively unknown for his critically celebrated film trilogy, which was begun 50 years ago in Oakland, and Mendocino, California.

While Schmidt is one of the few independent filmmakers to be honored by a listing in Halliwell's Filmgoer's Companion, which prides itself on its emphasis on Hollywood, Schmidt's feature films have only recently been made available to the public in video stores across America, and to those Britons who were fortunate to be among the 352,000 who saw (SHOWBOAT)1988 broadcast in June (1980, again in 1982) on England's new Channel Four. By the very nature of his films, intertwined structures of reality and illusion, documentary and fiction, it is not surprising to either Schmidt or myself that his work continues to confuse, and at times enrage critics. After reviewing two of Schmidt's features when they showed at the City Movie Center, the main critic for the Kansas City Star made the statement in print, "For lovers of weird movies, independent director Rick Schmidt is the king."

(Back cover) SLEEPER TRILOGY––Three Undiscovered First Features by Rick Schmidt, 1973-1983.

—————-

THE Q & A

BL: I noticed in your filmology that Wayne Wang was a co-director on your first feature, A MAN, A WOMAN, AND A KILLER (1975). Why don't we read more about this film, given Wang's recent successes?

RS: To be truthful, I'm not exactly sure. When Wayne and I did an in-person show at a local museum to show the film, I was recording the question and answer session when Wayne made the statement that A MAN, A WOMAN, AND A KILLER was "...a great little film." Then, strangely enough, when the first press came out about his success with CHAN IS MISSING, he called our film "pretentious." This flip-flop wasn't a total surprise to me, since Wayne had expressed his dislike for the film when it first was complete in 1975. He seemed to warm up to it a bit after one of the toughest critics in New York, Jerry Oster, called the film "...one of the most absorbing films I've seen of what is generally called the independent filmmaking movement." (New York Daily News, March, 1975). It was always my feeling that Wayne had been embarrassed that it didn't look like a "real" film. And of course, when the Asian-American cast and crew "hysteria" took place surrounding the production of CHAN IS MISSING, my editing on the final cut of that movie...was hushed up...another embarrassment. It's upsetting for me that our friendship was damaged by these collaborations, and also upsetting that A MAN, A WOMAN, AND A KILLER has remained so obscure.

BL: How extensive was your contribution to the final editing of CHAN IS MISSING?

RS: I imagine it depends on who you ask... When Wayne hired me to help with the final cut, I had heard from other friends who had seen it that there wasn't a third reel. I don't think it was really that bad. But there were structural problems that I solved by shifting scenes around and designing a dynamic opening credit sequence. I spent a month editing on the film. For hours I sat there pulling extra feet, extra frames from scenes while Wayne was away. I paired a shot that was not in the rough cut Wayne had edited, with a song that was in the middle of his cut, and suggested to him that he use this as his opening. In the shot, an old cab driver is filmed from outside his front windshield, with reflections of light sky and dark Chinatown buildings slipping down the glass. I thought of the idea of using alternating white and black credits that would play off of either black or white reflections. Backed by the song "Rock Around the Clock", sung in Chinese, the shot of the cab driver introduced the main character of the film, and gave the film the necessary Asian-American flavor Wayne was seeking. I did everything that invisible editors do every day on films; I cleaned up the cuts, designed transitions, threw out unnecessary footage, corrected the pace, supervised the AB rolling (matching the 16mm workprint to the original footage, necessary to make a print), prepared the sound tracks for the mix, assisted at the mix, oversaw the printing at the lab.

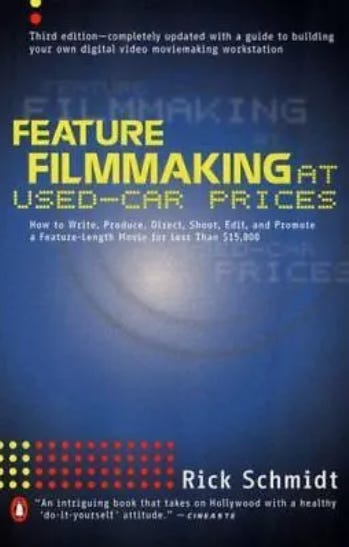

BL: You've written in your soon-to-be-completed book, Feature Filmmaking at Used Car Prices, that "to successfully edit a low-budget feature the filmmaker often needs to turn a sow's ear into a silk purse." What role has editing played in your development as a film-artist.

(Viking Penguin Books. ©1988 Edition).

RS: Editing for me is my main area of concentration as a filmmaker. Not only does it take the longest period of time to complete the editing of a feature, but the mental and emotional exercise of really understanding the footage and engineering the intelligent flow of thoughts and ideas is a thrilling adventure. Films that are shot from original concepts and intuitive camera moves always require great amounts of experimentation in the editing room, before the film's solution is uncovered. Each of my features has the structure of multiple juxtapositions of scenes and ideas. And since they haven't been edited for the audience's sake, but for the most dynamic exchange of ideas and information, some audiences are incapable of responding. But occasionally the films do find their correct audience and are appreciated.

BL: Can you explain to me the idea or ideas behind your feature trilogy...in the most simple terms?

RS: The three films represent three steps toward becoming a successful human being.

A MAN, A WOMAN, AND A KILLER is about trying to "see" your life in clear terms.

(SHOWBOAT) 1988 is about taking "risks" to make your dreams come true.

EMERALD CITIES is about "making your own life" in spite of the external pressures of the nuclear age.

BL: Can you briefly explain how you challenge the audience with these concepts in each of your features?

RS: A MAN, A WOMAN, AND A KILLER plays between the story of the film and the off-camera moments of the film being made. The performers are caught on film as their real lives intersect with their acted roles. In the middle of the film, actor Ed Nylund speaks about how a long monologue he just performed doesn't represent him at all, even though it was totally convincing. Each actor has an opportunity during the film to tell his or her "life story." As "real" scenes are juxtaposed with "scripted" scenes, the audience's point of reference is continually changed. But by the end of the movie they have either walked out...mumbling that it is "weird" or "confusing," or they have stayed to reach the point where the character Dick speaks the words, "Free will is just a joke as far as I'm concerned," just before he gets shot down by a hit man, ending the film. The best response an audience can make is to reject Dick's words and decide to change their life for the better. It's hard to see one's own life separate from those surrounding it, but hopefully after a viewing of this film, this may be possible.

(SHOWBOAT) 1988 is about a dying librarian who tries to remake the musical Show Boat on film for the impossible sum of $10,000 (the amount of grant money I received from the American Film Institute). Once again I used juxtapositions, placing pictures of librarian Ed Nylund's growing up against pictures of Ed's real crippled sister, cut against a drag queen (Sylvester) singing. And after you see Ed succeeding to create this free-for-all audition, you are told by his voice during the end credits that he really didn't make his dream come true...he just was an actor, and that he still works his job at the library. The audience for this film is jerked between the aspirations and reality of making a dream come true, only to learn at the end that nothing was created, no dream fulfilled. In the editing I tried to create a structure that would put the responsibility of "doing" back on the audience. The final subtitle in the film, at the end of the credits, reads, "Be the star in your own life."

EMERALD CITIES juxtaposes punk rock, the Santa Claus myth, nuclear war, self- hypnosis, psychedelic drugs, video manipulations, and a general laundry list for 1984. When Santa (played by Ed Nylund) is gunned down at the end of the movie, and punk band Flipper screams its dirge, “Love Canal,” (..."our common grave is the Love Canal!") it's my hope that the viewer can stop being distracted by horrific world news, focus finally on real life. At the end of the film I appear wearing actress Carolyn Zaremba's hot-pink dress, explaining that she ran off before the filming could be completed, to "make her own life" in New York as an actress. At one of the in-person showings I had for EMERALD CITIES, I told the audience that I wanted to change the old saying to..."you can run away from your problems." This, of course, infuriated some members of the audience, who actually approached the stage with looks of vengeance and fists clenched.

BL: Sounds like each of your features makes huge demands on the viewer. What kind of shows were you able to get with EMERALD CITIES?

RS: Actually, I had pretty good luck, with several commercial theatres putting it on the screen. The St. Marks Theatre, which operated until recently in the East Village of New York City, screened ‘EMERALD’ at midnight for two consecutive Friday and Saturday nights. Also, the Electric Theatre in San Francisco, and the Nuart Theatre in Los Angeles gave it premieres. In England, the Everyman Theatre ran it at midnight and the Australian Film Institute selected it for a seven-city tour. And it was shown at Film International Film Festival in Rotterdam, for which I was flown over for the screening. Fabrizio Fiumi from the Florence Film Festival saw it there and selected it for his festival in Italy (1983). I also toured in the U.S., showing it at about twenty showcases. So it did see a bit of daylight.

BL: When you think of the difficulties in structure and form that your features present, you aren't really surprised when a critic responds negatively to your work, are you?

RS: On the contrary, I'm always caught off guard when I get a good review or win an award or grant. I've been very fortunate to have succeeded as well as I have with these films. Each film has received some major attention. A MAN, A WOMAN, AND A KILLER won Director's Choice at the Ann Arbor FIlm Festival (oldest independent film festival in the U.S.). 1988 was selected by the London Film Festival (1980), and bought by Channel Four in England.

BL: Didn't you have to censor 1988 because of problems with MGM?

RS: That was just after the premiere at the Whitney Museum in New York. New Line Cinema had decided to distribute my film and it actually looked like I could pay back my lab, W.A. Palmer Films, Inc. of Belmont, as well as my mother who had loaned me needed money to complete the film. Then disaster! Some member of the Jerome Kern or Oscar Hammerstein family must have caught one of the Whitney shows and reported it to MGM, who held the ownership on Show Boat 1936, and Show Boat 1951. In their legal telegrams they threatened the Whitney Museum with damages and stated that I couldn't even "refer to Show Boat material." Somehow I was able to turn my depression around and keep trying. After the distributor dropped the film, I went to see a second lawyer for the arts in San Francisco, named Tom Steel. Tom had defended cartoonist Dan O'Neill who had been threatened by Disney over the copyright to Mickey Mouse's image.

After I heard that some scenes were legal, some not, I decided that the only way I could continue to show the film safely was to censor the entire thing. I filmed Tom giving an introduction to the film, indicating that Show Boat references would be "blipped" out, Showboat graphics "X"ed out, and Showboat songs removed, with subtitles inserted telling the viewer what had been removed. And, strangely enough, all this obliteration made the film work even better, bringing into stronger focus the problem of a "little guy" (Ed and me) trying to make a dream come true in the face of overwhelming odds.

(CLICK TO SEE: 1988 trailer here!)

BL: In May of 1984 you were included as one of ten filmmakers in an American Film article entitled "10 Cheap Movies," in which they stated "Rick Schmidt has low-budget filmmaking down to a science," and even teaches a college course called "Feature Filmmaking at Used Car Prices." How close are you to completing the book you're writing of the same title, and what are your plans for doing other college level feature film workshops?

RS: It seems after each film project I need a few years to recover, both spiritually and financially. A year after I finished EMERALD CITIES, in1984, I taught a feature film production workshop at Oakland’s California College of Arts and Crafts (now called California College of Arts and located in San Francisco), where I had received my MFA in film. During three months of a summer session I worked with three students to write, direct, film and complete a low-budget feature. Although we didn't make it to a feature length, our film, THE (LAST) ROOMMATE (50 minutes, color, ©1985, & ©2024) recently received a three-star review in the Kansas City Star, citing in headlines, "Big Ideas On A Budget."

During the class sessions, I tape recorded each day and transcribed the words each night. After this first "diary" of the class production, I caught the attention of a literary agent who suggested I write a "how-to" book with my title, “Feature Filmmaking at Used Car Prices,” including a chapter on my filmatic adventures over the last fourteen years. I'm now 3/4 done with the writing, and presently awaiting word from publishers. What I'd like to do is spend a year at one school, a year at another school, in each case producing a feature film with student collaborators, using my book as a textbook. Even though students Mark Yellen, Peter Boza, Tinnee Lee and I discussed the difficult issue of abortion in THE (LAST) ROOMMATE, we succeeded because I was proven right in my faith in their abilities. As soon as my book is completed I will approach such schools as La Foundation Europeenne Pour Les Metiers d'Images et de Son, and other similarly progressive institutions where making a good feature film with students would be possible.

END

————-

©2000 ‘Digital Edition’ available here: THRIFT BOOKS, ABE BOOKS, AMAZON, etc. (and at BUNCH OF GRAPES BOOKSTORE, Martha’s Vineyard, for other 'FILM' titles).

————-

***

REVIEWS of Rick Schmidt Movies

“An extraordinarily intriguing first feature, [A MAN, A WOMAN, AND A KILLER] by west coast filmmakers Rick Schmidt and Wayne Wang. Beautifully shot in a California landscape, the film flows back and forth between the fiction of a script and the half-submerged reality of the actual writing of the script. The use of subtitles in an English language film add to the fascinating complexities of content and form.”––Marc Weiss, BLEECKER ST.CINEMA, POV

“A MAN, A WOMAN, AND A KILLER is a tragic epic, a love story, a documentary about drug addicts, a comedy, a portrait, a commentary and a tapestry. Mostly, however, itʼs a film about violence. Not Pekinpah spleen-punching violence or Coppola bleeding-horses-heads violence––by comparison these are cartoons, embarrassingly vapid, self-indulgent and boring. Only one other film, to my knowledge, comes close to describing the sort of violence found here, and that is HELLSTROM CHRONICAL. To watch a housefly fighting uselessly for its survival in a glistening, perfectly engineered spiderʼs web is truly the most violent life struggle put to screen. The man (Dick Richardson) in this film, is in many ways like the fly. Very ordinary. Not particularly likable. Not particularly comely. Not particularly interesting. Just a man. But curiously, as the camera moves in ruthlessly close, he becomes an extraordinarily beautiful specimen––at the same instant wild and fragile, wizened and puckish, gentle and fierce. We donʼt want to love him, but in the end we do.” ––Linda Taylor

Directorʼs Choice,

Ann Arbor Film Festival (1979)

***

“Hollywood has made three versions of Show Boat, but none of them is remotely like SHOWBOAT 1988.”––Bob Lundegaard, THE MINNEAPOLIS TRIBUNE

[“SHOWBOAT 1988” was] “The big hit of the Ann Arbor Film Festival, itʼs easy to see why. The film has carved a unique niche for itself somewhere between FREAKS and Fellini's 8 1/2. Itʼs as though someone forgot to lock the studio door and Luis Bunuel and William Burroughs sneaked in and began a hatchet job on Hollywood." ––David Harris, BOSTON PHOENIX

“The tryout sequences [in SHOWBOAT 1988) are both delicious and dismaying, reminding us in poignant moments of A Chorus Line and (more often) in silly moments of the tryouts in Mel Brooks' The Producers.” ––David Elliot, CHICAGO SUN TIMES

“What a truly strange mixture of ingredients. Emerald Cities is the apocalyptic abandonment of A Boy and His Dog intertwined with Chris Marker's media integration. The scathing punk of The Driller Killer with the wandering outsiders of Harmony Korine's films. Perhaps the only film which could claim similarities to both 70s Godard and Freddy Got Fingered.

“A film which contemplates the US racing to oblivion, the absolute annihilation of a culture already plunged into its own dark age, by questioning random citizens about their belief in Santa Claus as a reflection of the loss of humanity. Constantly subjecting the audience to extended punk performances as a means of visually and audibly channelling anger.

“Emerald Cities lives and dies as a contradiction - it's absolute anarchy yet also intricately and searingly edited. On the surface you could possibly argue that it's so angry that it loses its way, but Emerald Cities would bite back that it's the US that is losing its way because people aren't getting angry. ” ––Jack Russo, Letterboxd

“I try to go into films I have never seen with as little information about them as I possibly can, and EMERALD CITIES is one that I am especially glad I approached in this willful state of not knowing. I truly love this movie. It is as close to seeming to be an “accidentally filmed” movie as I’ve ever seen. The performances seem to be barely that, more just thoughts and conversations and moments captured by the camera, which always seems to just happen to be there. Interspersed with real life news segments and concert footage from the time in which it was made. If all of this is intentional, if all of this is orchestrated by the filmmakers (which it seems to be) it is perfectly executed, so vivid and real seem every moment of this constantly engaging document of the extraordinary stories of some ordinary people living in the Reagan’s America in the waning days of 1983. A terrific piece of cinema.” –– Sid Collins, Letterboxd

————

SLEEPER-TRILOGY-Three-Undiscovered-First Features-1973-1983.

————-

This post is so full of soulful observations about transcendence I couldn’t begin to summarize them in a comment. But one thing I must say, Wayne Wang’s remark, “it didn't look like a ‘real’ film,” stands out for me as great summary of how NOT to judge one’s own or another’s Way. Searching for some “Real Way To Live,” to try to align to or mimic, is a Dead-End Trap. Follow Your Own Map.