MORGAN'S CAKE movie--it's actually all about the EDITING when you shoot IMPROV like this. If you had actors "freeze" & changed angles, w/great (B&W) images & storyline, then finish with a TIGHT cut!

Watch MORGAN'S CAKE (87 MIN., ©1988): <https://vimeo.com/168153085>.

Excerpted from book, THE MIRACLE OF MORGAN'S CAKE––Production Secrets of a $15,000 IMPROV Sundance Feature").

Playing the Serendipity Card

Given that I didn’t even know if Leon Kenin’s father would be around the house while we were shooting there (Leon played and was/is a best friend of Morgan’s), much less that he’d agree to be in the movie, do you think I left my moviemaking process too open to chance? Would I have been better off taking the time to drive over to Leon’s house, scouting out the rooms beforehand and broaching the subject of his parent (mother or father) appearing in some future shots? In some instances, all the moviemaker will do with pre-production planning is set up a fear-zone, the anticipated arrival of his/her DV cavalcade seen as an increasingly intimidating prospect for the “victims.” If regular people, friends and family members (non-actors) know you are showing up in a few days to use them in your movie, they may, over time, decide to spare themselves the risk. They may suddenly have a bad hair day, or remember being terrified giving a speech in high school. Sometimes you’ll lose the borderline contributors by conducting the “professional” pre-production house visit and scaring off those individuals who would only get in front of your lens at the very moment of shooting.

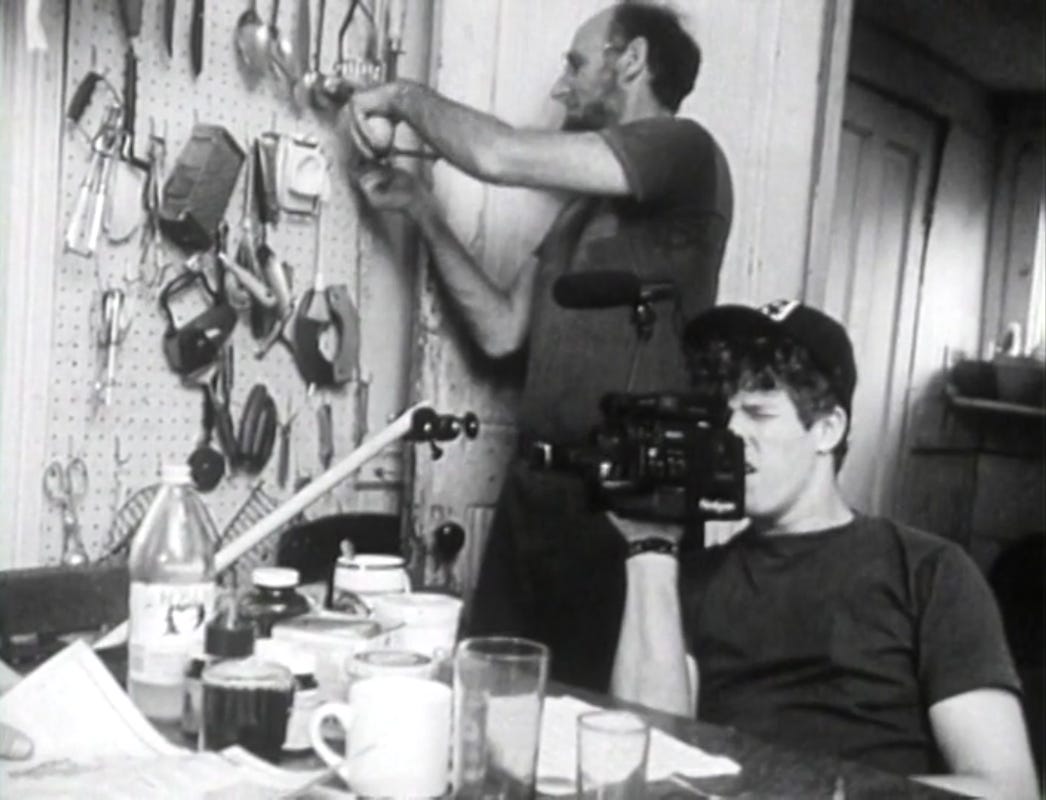

Eliot Kenin and Morgan with camera.

Here’s how the spontaneous addition to the cast came about in the case of Leon’s father. When I noticed Eliot was in the house, I asked Leon if he thought his dad would mind being part of a scene. He told me to ask. Eliot somewhat hesitantly listened as I explained the gist of the scene (which I had just made up on the spot), and how I thought he could interrupt the boys at the table when he spotted Morgan’s expensive-looking video camera.

I gave Eliot a quick thumbnail description of Morgan and his dad, Willie’s, low- income background, explaining that they were living in a one- room office where Willie slept on top of the desk, with “son” Morgan on the floor. So Eliot had no time to build up the scene in his mind, imagine the words he’d speak or how he looked on that particular day, what he was wearing, etc.. Ten minutes later we had wrapped up that “Leon reading Grab Bag with Dad interrupting” segment. The final image at the end of my wheelchair dolly (thanks, Kathleen, for rolling me back and forth!), of Morgan’s eye pressed against the eyepiece of the Hi-8 camera, gave me the idea to record some additional color video footage at Leon’s house, something I could cut to later from the B&W scene.

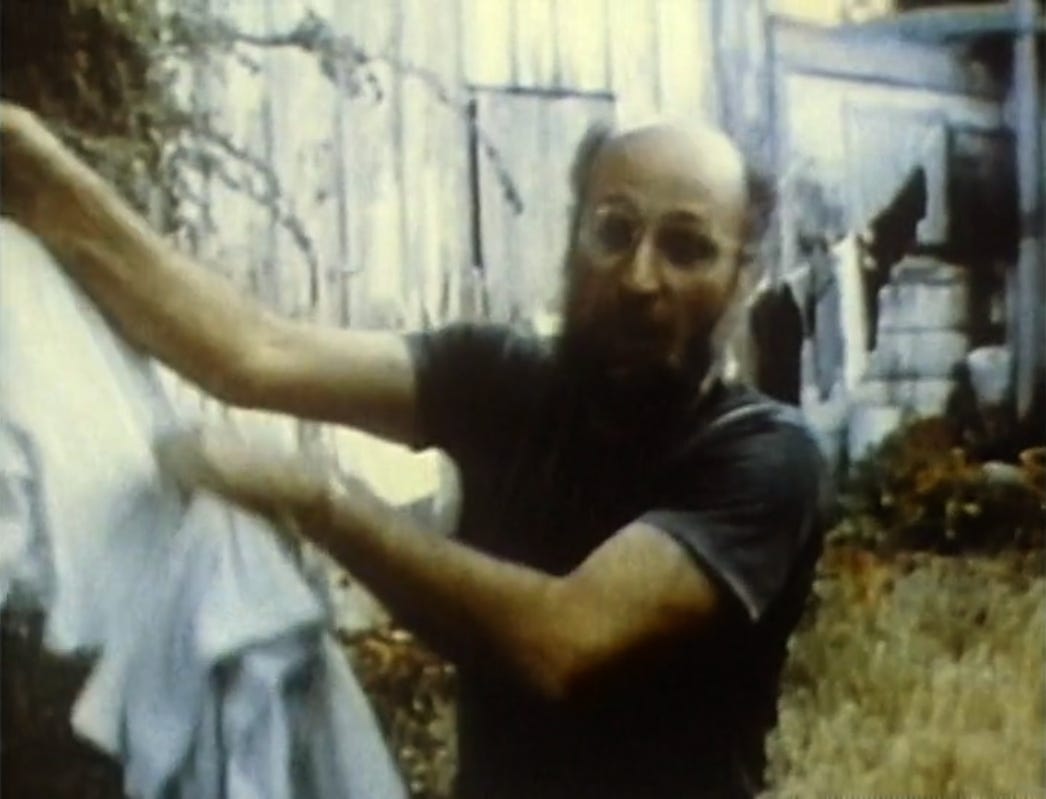

Again, it was a flow of ideas and actions that lead me along. I don’t think I told Morgan to stick his face against the eyepiece. It just happened that he took that pose naturally, which gave me the next thought. After I called Cut at the table, I asked Eliot if he had anything he could talk about relating to our draft registration theme. After thinking a second, he said he could tell the story of how he avoided the draft in the 1940s. Great! I responded, asking, Where should we shoot it? I wondered out loud, adding, Somewhere outside would be better light for us. Eliot answered, I have to take some dry clothes off the line in the back. How about if we shoot there while I place things in the laundry basket? By inadvertently having a real-life activity that was demanding his attention, Leon’s dad designed the action for his own shot. So the activity of the scene (taking down the wash) depended on what exactly was happening in real-time on that particular day. We wouldn’t have had the same situation available to us during a location scouting expedition, if we had visited days earlier.

When you pre-plan every shot with a pre-production schedule, you begin stripping the movie of its flow, and undercut the level of reality. While I’m not suggesting you totally deny your production a policy of preparedness, I’m trying to instill some confidence in the flow of the shoot. If you don’t plan every detail, but just jump into situations, you will often be surprised at the abundance of cinematic gifts that materialize, like that that Eliot so gratiously supplied.

NOTE: Don’t bypass great scene-making situations (or forgo suddenly available non- actors) just because they aren’t listed in your script. Take advantage of everything you see and feel during the actual days of shooting.

Romping Visuals With Morgan

After almost a week and a half of shooting the meat-and-potato sync-sound shots, and on a day during which only Morgan was available to act and my soundman needed a break, Kathleen, Morgan and I took off in her car, driving around the Bay Area to shoot a series of silent images. The shots would include Morgan “romping around like a gorilla,” playing off the line I’d tossed to Lulu during the mother-son scene. I imagined the silent shots would be backed up with sound/music later. So we headed to San Francisco and first shot Morgan loping along, ape-like, down the sidewalks, past the strip joints of North Beach. We then shot Morgan continuing his gorilla romp near the gate of San Quentin prison, at the Marin headlands by the Golden Gate Bridge, and back across the bay at a Berkeley park.

While such MOS (without sound) cutaway shooting seemed hardly like serious work – there was no dramatic moment of rolling sound and clacking a clap board – it became clear later in the editing room that we had gained vital shots for the all-important “cake-making” montage, needed to wrap up the movie.

Embracing the Unknowns of a Great Location – Thinking Structurally.

In the days before we were set to shoot at John Claudio’s uncle’s large house in the Oakland Hills, Morgan kept mentioning the various attributes of the location. He said he had seen an incredible gun collection belonging to John. And he talked about a hot tub he’d spotted in the central courtyard. OK. Guns and hot water. We’d use them in our shots! What else? I had no idea what restrictions might apply to various parts of John’s uncle's house, and just proceeded with a positive attitude. I hoped we could get the crucial shots at the front door (seen from outside and also the inside reverse angle) where Morgan and Rachel would be standing when they return the Hi-8 video camera. I really didn’t feel like trying to make contact with the uncle before the day of the shoot, for fear I might lose that location. In this case, I allowed my paranoia to prevail and just awaited John’s phone call, hopefully saying that we could go ahead as planned.

As soon as we got the OK we gave John a half-hour window during which to expect us, and he said that was fine. I reminded Rachel and Morgan to pack their swimming suits, and told them not to forget to bring the Hi-8 camera and pole. Before we started over to John’s, Morgan let me know the video pole’s bracket wasn’t working properly. For some reason, it had refused to tighten down completely. So the camera just sort of just drooped at the top. I told Morgan he would apologize to John about it, act contrite for breaking something, when he returned it. The idea of faulty equipment would now introduce a line of dialogue, and actually, the broken bracket concept also led to a good adrenalin moment for the hot-tub scene coming later.

How will the scene start out? Morgan asked me. It’ll be you and Rachel driving along in your pickup, looking for the address, 42 Crest (from the sticker on the video-pole), I told him. I squeezed into the Toyota pickup on the passenger side as Rachel moved closer to Morgan, so I could include both of them in the frame. This shot would have been impossible without Kathleen’s super-wide-angle lens. (For you DV moviemakers who lust after the Canon XL-1S, you’ll need another bunch of $beyond the cost of the basic camera, to purchase such a special lens. Renting, in this case, may be a good option).

I instructed Rachel to just chatter away in response to seeing the huge, expensive-looking houses they passed on the way to John’s. Morgan couldn’t help jumping in, correcting her when he felt she over-estimated the value of one of the mansions. Anyway, we got some good traveling shots that included little snippets of real-life squabbling between boyfriend and girlfriend.

Arriving at John’s, I had Morgan park as I continued to shoot. Then I cut the camera and asked Rachel and Morgan to stand in a spot where I could make “42 Crest” seem even grander, by letting a tree hide the gap between John’s uncle’s house and the even-larger mansion next door. After shooting for about thirty seconds, holding a static shot from ground level, I voice-commanded them to start the long walk across the street, up to the front door of John’s house. Later, Gary Thorp’s musical score – accentuated by the sync sound recording of a few cars passing by – would add the perfect mood of apprehension to their approach.

Since I had never been to John’s house before, I had to figure on solving the shooting problems real-time, as they appeared. So I had my moviemaking antenna activated again, sensing the right path of shots, intuitively selecting the best camera placements, figuring out angles and cuts (“editing in the camera”) so shots would fit together in the editing room. And I gave voice commands as inspiration dictated. As soon as the walk to house was wrapped, Kathleen, Nick and I crossed the street, greeted John, and entered the house to set up the next shot from somewhere inside.

Book is free if you have a Kindle account (and paperback is pretty affordable). Plus check out MORGAN’S CAKE TRAILER IF YOU SCROLL DOWN): https://www.amazon.com/dp/B075FHS8KB

————

As we pressed by John with camera in my hand I noticed that a mirror on the adjoining entry hallway wall beautifully caught our reflections. Good. I’d set up my framing to include Morgan and Rachel’s images in the mirror when the front door opened. With John’s help, I aligned my first interior shot, discovering that in order to frame the mirror’s reflection I had to shoot from the last step of the nearby stairs. That gave me the additional concept of shooting John from behind as he stood higher up on the stairs, then following him down for a few steps (stopping on step-one) as he reaches the floor level and answers the doorbell. Making that decision to start with John lurking there on the higher stairs added a new element of drama, as if he expected his visitors and was watching for them. John peering out through the small window off the stairs suddenly made him a foreboding presence, like Vincent Price was in The Fall of the House of Usher.

After a few tries at walking with the camera and stopping steadily at the correct last step (not so easy a camera move), I got it right. The mirror reflections of Morgan and Rachel looked pretty good through the lens when I rehearsed, so I went for it on the next take. Morgan immediately made the “broken video bracket” apology as planned, and John just naturally supplied his side of the dialogue, OK, no big deal. Once inside the high-ceilinged house I called out Freeze! and quickly set up for a reverse angle while all actors stood frozen in position. I had noticed that Rachel had naturally hung back to check out the intricate wood-carving on the interior of the front door, and I kept her there to milk the shot for all it was worth. Her bumbling dialogue (in awe of the mansion, grand riches, etc.), was effective as Morgan slowly entered at John’s invitation

Calling Freeze again, I told Rachel to again repeat the action (inspecting the carved door) and started rolling. Finally, with a hand outstretched, Morgan reached back into the frame, urging her to grab a hold (she did that without my instruction), pulling her into the large room as I followed with the camera to where John stood. If the pan hadn’t worked out smoothly (actors in focus, camera steady) on that first impromptu attempt, I would have called for a retake. Other than that, I was shooting a 1:1 movie, and tried not to shot anything twice that I thought was OK on the first take.

After shooting introductions (in the movie’s narrative, the three had only met briefly at the beach), John rushed off with the camera and pole as I had earlier directed him to do, leaving Morgan and Rachel to take in the expensively appointed living room. There were rare-looking oil paintings, a gleaming black piano, high-quality rugs, etc. As soon as I’d shot them from a few different angles (“Freeze” called each time before moving the camera and tripod as a single unit. and settling them on the central couch), I realized it was time to try a scene I had actually scripted.

Months earlier I written a scene where Morgan made a connection between the cost of his clothes and the slim wages he was earning. Originally, it called for Morgan to have numbers written on various items of his clothing; “1” on his socks, “5” on his jeans, “2” on his shirt, “9” on his sneakers, “5” on his watch, and so on. When someone asked Morgan what all the numbers meant he would respond that the numbers equaled how long, in working hours, it took him to earn the money used for purchasing each part of his wardrobe. In real-life he had often complained about the cost of such items, and that had given me the concept for a funny scripted scene. But as we were without the prop of clothes with numbers painted on, I directed Morgan to just swing his head around and talk over his shoulder directly into the camera.

I suggested he play off what he felt actually sitting there in the large, well-appointed room. Maybe he could wonder how many hours it would take him to own what he saw, compare his wage per hour to some of the expensive things there. I told him to also talk about imagining a life there with Rachel, the two of them getting to live as a real, well-heeled couple. As I’d done before, I reminded Rachel to pay no attention to the camera or to Morgan’s upcoming soliloquy.

Here’s the sub-title text for the dialogue Morgan improvised from my prompting:

Morgan: When I look around the room,

and I look at all the things in this room...

...I feel as if I’m sharing this room, or I’m...

...this room is my own. And I wonder...

...how many hours it would take,

for me to own all these things here.

It took me...five hours...just to purchase this watch.

...Five hours of work. I wonder how many hours it would take…

...for me to just own one square foot of the ceiling.

But for right now, Rachel and I, we kind of feel at home here...

...as if it’s ours...these few moments together in here.

As soon as Morgan made his point I ordered, Turn around. As soon as he turned he naturally kissed Rachel. I then instructed, Put heads together. After they did that, I commanded, Don’t move! Because I was shooting from the back, that command was easy for them to carry out (harder to see any fidgeting). I kept shooting this static shot, of the young couple seen from the back of the couch, until almost the end of the film roll. The sequence ended when I waved John back in, as if he was returning from upstairs.

As I've indicated before, voice-commands must be short, just a few words long, and delivered only when you can best gamble on an actor’s temporary silence while the camera (DV or film) is rolling. And, of course, the actors have to be taught not to respond on-camera, to your verbal command. When you suddenly speak a command from off-camera actors/non- actors have to act like they’ve heard nothing at all, then do exactly what you’ve instructed.

NOTE: Remember that in digital computer editing you can easily remove any voice-command spoken to the actors (see Extreme DV, Chapter Five, “Tips for FCP Finish Editing”), as long as your voice doesn’t interrupt sync-sound dialogue.

Imagine what it must have been like, being in an audience watching Morgan’s Cake during this minute-long static shot of the backs of Morgan and Rachel. Nothing moved. And there was no music, no sound effects enhancing the mood (a few cars could barely be heard passing along outside the window...). It was virtually a gigantic snapshot on the screen.

At one of the very best shows we had with this movie, at the New York premier in Alice Tully Hall for New Directors/New Films, approximately 550 people sat in silence, living and breathing together with the two teenage characters stalled in that upper-crust environment. Was it preposterous to expect an audience to tolerate such a long “nothing” shot? No, not if the overall structure of the movie up to that point made such an extreme, unconventional moment acceptable to the viewer. I just prayed that no one would cough or get up and leave the screening, thus wrecking the precious-to-the-movie narrative moment.

As the silence stretched out past half-a-minute I felt the movie “fold over” on itself, forcing the viewer to contemplate some of the movie’s themes. Questions arose, such as: Where did a kid like Morgan fit in the world? Would he ever attain nice living quarters, like the well-appointed space in which he found himself? Would he and Rachel’s relationship last? Would Rachel terminate her pregnancy? Would Morgan ultimately register for the draft, or not?

Maybe a bigger question enters an audience’s mind as the silence extends: What kind of trade-off is required for reaching material success? Isn’t that one of, if not the main dilemma, that entangles our modern lives? At any rate, audiences seemed content to experience Morgan and Rachel existing there, in their temporary environment, with its accompanying minute of zen stillness.

————-

"If you don’t plan every detail, but just jump into situations, you will often be surprised at the abundance of gifts that materialize." More wisdom that flows in "Real Life" as well as creating Art. "Jump in!" And, this is not foolhardiness at all. It's a "knowing" that Life LOVES you and LOVES giving you gifts. KNOWING.