MORGAN'S CAKE (87 min.)--watch 4 FREE: <https://vimeo.com/168153085>). I relied upon teenage non-actors for IMPROVISING scenes I instantly made up, as new ideas and filming opportunities crashed in.

READ BOOK: <https://www.amazon.com/dp/B075FHS8KB>.

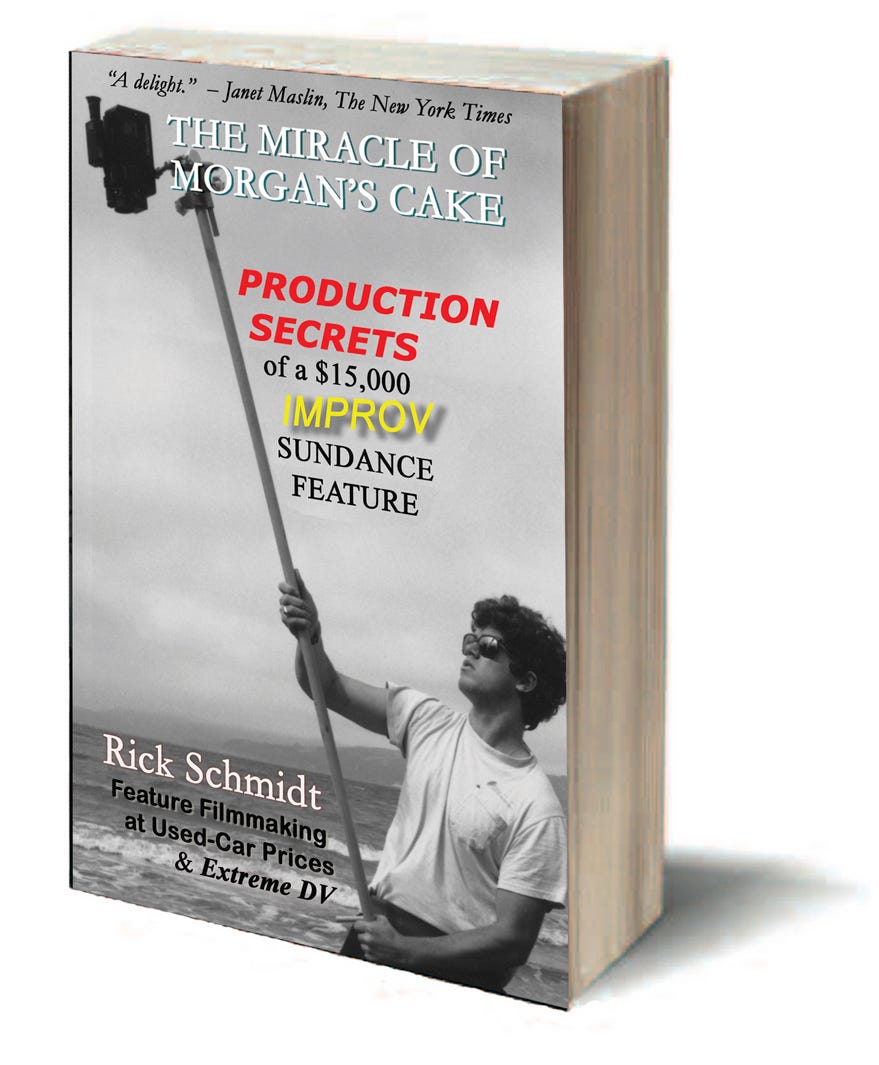

Excerpted from book, THE MIRACLE OF MORGAN'S CAKE––Production Secrets of a $15,000 IMPROV Sundance Feature").

Office Wide-Shot/Spatial Coverage

After that highly productive Sunday morning shoot, and a quick lunch, I got ready to shoot Morgan talking on the phone to his “Sears boss.” I set up for a wide-shot of the Jumbo’s building from about 100 feet away. As the shot began, all you could hear was Morgan’s voice, a one-way conversation recorded by Nick from up in the tiny office. Because we were running "crystal sync," I could shoot sync sound from far away as long as a slate was clacked together that Nick could hear and I could shoot. For DV you would need some radio mikes with a strong transmitter to duplicate this long-range sync scene. According to the instructions I’d given him, Morgan eventually appeared in the window, removing any confusion as to where the sound of his voice was coming from.

From the change in the tenor of Morgan’s voice as the call progressed, it quickly became apparent that he’d been fired, adding another conflict element to the teenage portrait I was developing. The wide shot, which took in almost the entire building, allowed me to show from a different angle the following; (1) the street corner where Rachel and Morgan had crossed at the end of the block-long, “cake and eat it too” dolly shot, (2) the window of the office Morgan had been looking out from in the first shot, and (3) the store-front exterior of Jumbo’s restaurant, from the little post office next door, and (4) the front entrance of the office building where Morgan had read the White House letter. So with just that one wide shot I supplied many reverse-shot needs from previous scenes, to give a full sense of local.

NOTE: The conflict/resolution cycle is a powerful one for building a gripping story. Give your characters an Everest to climb and an ice stormtoderailtheeffort. Pileupconflictwhile offering new real-life information that is particular to your project.

By the end of the phone call, Morgan had laid out several more conflicts I could make use of in developing the story. We’d learned that Morgan had been fired from his delivery job because of the missing refrigerator, which meant no money for rent (again, referencing dialogue already spoken). And when Morgan added that he would probably lose his truck as well, that gave me an idea for the next scene. Before I closed down the phone call scene, I grabbed a few pickup shots, with sync sound, of Morgan on the phone as seen from the sidewalk directly below. I noticed the large American flag hanging above the entrance of the small post office and included it in my framing from several different angles. As a light breeze blew the flag around in the foreground, I shot a series of cutaways where Morgan was momentarily blocked from view by the flapping cloth.

NOTE: Always shoot cutaways to protect your master shots. Shoot a character’s hand reaching a door knob, her shoes walking along the sidewalk, an eye peering right to left, something close-up to make sure you supply the editor/yourself with the components necessary for a successful cut.

Connect Dots/Build your Moviemaking Riff

To take advantage of the low-traffic flow in Point Richmond, I decided to next shoot Morgan driving angrily through town in his soon-to-be-repossessed Toyota pickup truck. I didn’t have to over-sell Morgan on his motivation. In real life, he knew well the threat of losing his wheels – he really was making car payments from money he earned delivering appliances. At any rate, the upcoming “Morgan drives” scene required that I make some quick decisions; (1) Where should I instruct him to drive, (2) where should he stop/park, and (3) what should he do once he kills the engine. His teenage world was suddenly crashing down, all because of someone else’s screw-up, and he was pissed to maybe an emotional level nine out of ten.

Of course none of this was in the script. I was “writing” as I went, flowing from one scene to new ideas generated from what had already transpired or been talked about. And, thinking as an editor, I continued to plug any structural holes in the overall scheme of the story. So, I thought maybe Morgan should...gun it up the hill...turn into the parking lot at the base of Nickel Nob (where he and Rachel had discussed the flying machine), giving us another view of the San Francisco Bay.

After an establishing shot of Morgan at the wheel, driving for a few blocks, I hopped into the back of the Toyota and shot toward the rear as he accelerated up the hill. I was looking back down toward Point Richmond’s main town square where we’d done the wheelchair dolly shot of Morgan and Rachel walking. And again, to connect up to my historical research, I figured I could incorporate another great turn-of-the-century photo of the town, one that pictured that exact same hill Morgan’s car was climbing, but set in time before there was even a road, just a deep-rutted, muddy path. As I kneeled in the pickup bed, shooting over the back tailgate, we passed the exact spot from which that old photo had been taken eighty years earlier.

Was I worried about figuring out how the scene should end? No, because I was too busy shooting camera, getting the good shots, good sound, completing the job at hand. And since I was shooting my own movie, scenes already completed were etched in my mind – as the operator of the camera you will pay THE MOST attention. So I could keep building conceptually on those previous shots. That’s the key to pulling off a tight movie without a full script.

NOTE: Shooting in a fully improvisational style, you must constantly think on your feet, make quick decisions, to assure that previous scenes you shot can fit cohesively into the overall movie-reality you are constantly constructing.

At the top of the hill, where Morgan drove in to park, there lay a few lengths of plastic drainage pipes, other pieces of garbage. As luck would have it (luck for the movie scene, not real-life luck at all), Morgan hit the pile perfectly, causing a pipe to bounce up and smack the underside of his truck with a loud bang. Out he jumped, without my urging (I'm still shooting), infuriated that he may have caused damage to his precious machine. He was hardly aware of my whirring camera thirty feet away. I think he probably broke character soon after that, calling for me to check out the damage as his dad. But I had the shot well in hand, another real-life production miracle that would make the finished movie better for its extra content.

Before we could end the scene, I had moved in for several cuts, closer up to Morgan, covering his truck, milking his displeasure. To top things off, Nick helped me temporarily disable the truck engine’s electrical system so it wouldn’t start, and I filmed the scene in wide-shot, of Morgan repeatedly trying to start up his vehicle. I ended the sequence by finally panning away entirely, to show the view of water and distant San Francisco beyond. So the pattern remained, that I would take advantage of any and all real events surrounding the making of my movie, incorporate everything that came my way, while forming the visual connections by overlapping previous shots.

Sound Man as Actor/Resource

My friend and sound man Nick Bertoni had a nice, old, rambling three-story Victorian house in Berkeley, with a backyard, garage, and basement jammed with his garage-sale treasures. I couldn’t help thinking it was a rich location. Nick responded well when I mentioned I’d like to shoot there, and even answered in the affirmative when I asked him to consider acting as well. The only problem then was, who would do the sound? Luckily John Claudio, who played our “rich kid with video camera,” offered to try. Nick got him up and running, instructed him about sound levels, aiming the microphone on a boom pole, and reviewing the particular’s before each take.

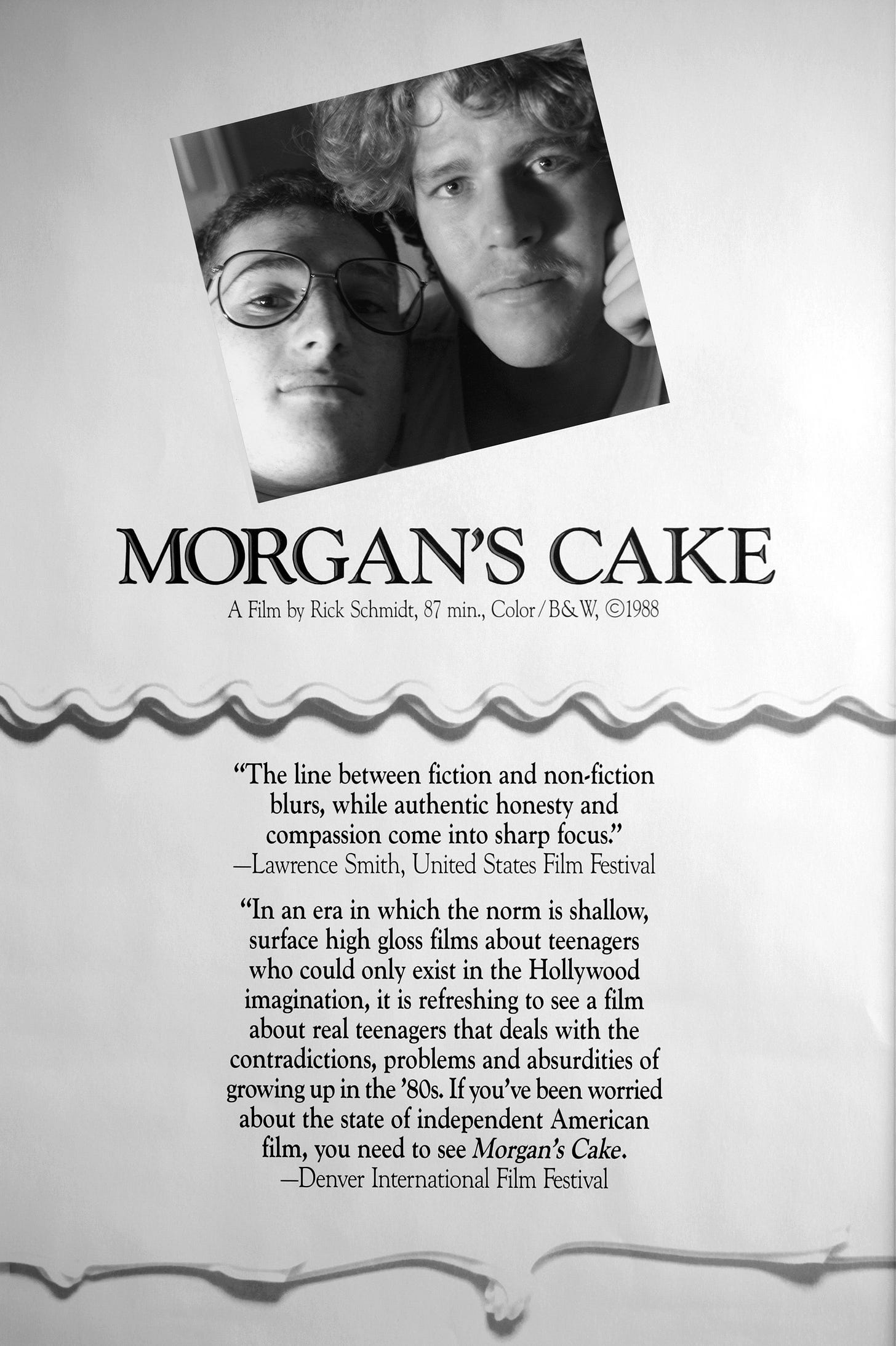

MORGAN & NICK BERTONI.

Kathleen had tried to pin me down about scenes/shots at Nick’s, and I tried to be accommodating, agreeing to meet her at his house a week or so before shooting began. Of course I had no idea what I wanted to do there, so I was nervous – what direction could I supply? We wandered around the backyard for a while, and suddenly it hit me. Maybe Morgan and Leon could be doing some yard work for Nick (I had done work there myself, to repay him, by the hour, for sound recording and a generous loan for Emerald Cities (my 3rd feature film, shot in Death Valley in 1979). In any case, Morgan and Leon could work for a while, doing some sort of light manual labor, weeding or something, then be fed lunch by employer Nick.

Having the three of them sit down together for a meal would provide an opportunity for conversation between the young men and the wise, older “radical” adult (Nick had a large white beard and looked a lot like a kindly Santa Claus). But Kathy told me to please stop being so general. She told me she needed specifics to do her job adequately. I felt pretty dumb as I stood there, no script in hand, with only a week to go.

I tried to shake off the humiliation of being “unprofessional” and made myself relax a bit. I knew that being nervous always scared all the good ideas away! Finally, some obvious questions came to mind. How would I keep Nick in the scene in the backyard? What would he be doing there while the boys worked? I was drawing a blank until Nick happened to show us a strange contraption he was using to stretch his back, a tubular-framed apparatus on which one’s feet were locked at one end, allowing a person to then turn upside down and hang there, letting their spine loosen and relax, right in the convenience of your own home! I had hardly noticed the device, as it was surrounded by tall grass, hanging laundry, other distractions. Maybe the boys would miss seeing it too, even with Nick suspended in it. Hey, I was finally getting specific ideas! Nick could be locked in, hanging upside down when Morgan and Leon arrive at his house. Maybe they’d call out his name, even wander within a few feet of him before he answers. And that gave me a chance to do an upside-down shot. I’d let Nick hold the camera and shoot Morgan, still filming as he swung from upside-down to right- side-up. Great. Finally I could give Kathleen something solid to work on.

Before we departed, Nick offered Kathleen and me some sandwiches, and before we finished lunch he brought out a box full of tiny Chinese herbal medication vials. The vials looked like miniature soda pop bottles only three inches high, each filled with a little dose of Ginseng. They were so cute, I thought, with their tiny sipping straws... Suddenly I got another idea!

Nick could offer the Ginseng to Morgan and Leon with their sandwiches, as they sat around Nick’s backyard table. Morgan could air his grievances to Nick, who had been a submariner in real-life, so a discussion about the military had some real potential. Anyway, I was relieved to tell Kathleen that “the action” would take place “at the table,” with “a discussion about...the draft.” But I also warned her that I’d be making a lot of spontaneous, last-minute decisions as we shot, and to please forgive me in advance for the seemingly-loose nature of my moviemaking style.

By placing myself under the pressure of working with a professionally trained cinematographer, I created a situation that forced me to generate some good ideas on demand. And that isn’t a bad thing. The cast of Saturday Night Live has used this process to good effect over the years. Michael O’Donoghue, one of the lead writers on that show, said that nothing comes without a deadline. So sometimes it’s worth imposing a deadline for getting viable moviemaking ideas.

One-to-One “Freeze” Sequence

The night before I was set to shoot at Nick’s, Morgan's friend and supporting actor Leon Kenin called to inform me that he could only join us at the shoot for three hours, between 3PM and 6PM. Just what I didn’t need to hear. Fortunately we were shooting in early summer, so the light would probably hold until about 7:30-8:00 PM. But I would have to work super-fast, even with my one-to-one “freeze” shooting technique. By building a series of shots wherein action and dialogue overlap slightly, I could create the entire sequence with a one-to-one shooting ratio. The only worry was, if one of the segments was faulty – out of focus or poorly framed – the entire house of cards could collapse. With a big gap in the middle of my series of on-the-spot cuts, it would be pretty hard to recreate a missing piece later in the editing room. So there wasn’t any room for mistakes.

Even with DV, the “freeze” technique of building a sequence is perilous. You still need to have a logical progression of actor’s movements and order of dialogue to complete a successful edit later.

On a movie set, three hours go by in a blur when you’re shooting. It feels like someone just pushed down the handle of a time machine and accelerated you ahead. Usually I think in terms of half-day chunks of time, four-hour stretches with hour-long meal breaks in between. To have only three hours with Leon would be tough, but I figured he could excuse himself from the table scene at whatever point his deadline hit (which is exactly what you see in the movie – Leon says he has to leave and he does). So I’d simply build his exodus into the scene. From there, after he left, I figured that I’d just continue shooting Nick and Morgan’s dialogue if there was more “draft philosophy” to finish up. That was the plan. By rethinking the problem of Leon’s premature departure I had regained some control over the uncontrollable.

NOTE: Remember the indie moviemaking mantra: Bad news on the set must always be turned to good advantage.

As shooting at Nick’s began, I first filmed the arrival of Morgan’s Toyota pickup as it turned into Nick’s driveway, and the two boys walked along the side of the house. I then filmed some dialogue about the upcoming yard work in a reverse shot, letting Morgan express his doubts about the under-the-table job. Leon responded with a line I had scripted, saying that Nick was “...a forward thinker.” and not to worry. That seemed like a good setup for the following shot (thinking about cuts in the editing room), where Morgan and Leon discover Nick hanging upside down in the back yard.

Earlier, when I had wandered around Nick’s property with cinematographer Kathleen, I had watched Nick hanging some large bed sheets on the clothes line. The bright sun turned them into glowing white ghosts shifting slightly in the breeze, forming lovely shadows on the ground. I asked him if he wouldn’t mind keeping them handy and hanging them up again on our shooting day and he agreed.

I guess that request got him thinking more like an actor than a soundman, because on the day of the shoot he had a live parrot on his chest while he hung upside down, making his character even a bit more eccentric.

You can see how one idea led to another as I proceeded to shoot at Nick’s house. As the series of events unfolded, in their proper sequence, I could keep my mind straight, build each element off the previous scene.

What would be the first logical scene after Leon and Morgan arrived for yard duty? Gathering the tools of course! So after filming the introduction of the Nick character hanging in the apparatus (I let Nick hold the camera, shooting Leon upside down before spinning around to upright position), I shot Morgan and Leon in the garage, gathering up a wide selection of weed-cutting tools. They laid out long-bladed knives, a few machetes, hoes, and what appeared to be a real hand grenade – the scene got a good jolt when Leon plopped that item down on the tool pile. And of course I really got them working, pulling weeds, digging out roots while I shot them from a few different angles. Finally I voice-commanded Nick to call them to lunch.

At the large round table which I had previously scoped out with Kathleen, I kept using “freezes” and changing camera angles as Nick served sandwiches and the boys started eating. It didn’t take much to get some heated dialogue going.

When Leon broached Morgan’s “draft registration” problem to Nick between bites of his sandwich, Morgan acted duly put off, first responding angrily about Leon airing his personal problems, then becoming frustrated with actual concern about being vulnerable to military service.

“I mean...just feels like...the registration just starts dragging you in,” said Morgan with a strained look on his face, adding, “That’s just the first give-in to the whole system of people getting killed, when they don’t even know what it’s for.”

“Do you want to go to college?” asked Leon.

“Of course!” answered Morgan. “I mean, everybody wants to go to college.”

“Well, you can’t get financial aid if you don’t register for the draft,” informed Leon.

This was the kind of information and drama I had hoped for. I had needed the actors (non-actors, really) to discuss the real-life facts of draft registration, detailing the exact consequences for one’s actions, and there it was. You can imagine how relieved I was after I shot that vital stretch of dialogue, laid in the main argument regarding draft registration.

Moments after that, Leon announced he had to split and I finished off the sequence with a close-up shot of the tiny, empty Ginseng bottles being placed on a large serving tray (hopefully a good comic effect, given the difference in scale), with handshakes crossing through the frame as off- camera voices said goodbye.

NOTE: Once you’ve identified the major theme of your movie, you need to create some critical dialogue (or images) that explains what’s at stake for your characters. If the audience worries about the life-choices your characters are making, they’ll become involved with your story. It might even give them a chance to transfer that concern to their own situations, start them thinking about the choices they are making.

Pre-Production Payoff

Well, as you can see from the filming in Nick’s backyard, there were some distinct advantages to having visited that set days earlier, before trying to shoot a complicated bit of semi-scripted material. At worst, I may not have thought of hanging sheets on the line for that visual effect.

Or maybe the back-stretch contraption would have been cleared out, stuck away in the basement, making me miss out on a fine sight gag and a novel upside-down shot. Also, if Nick hadn’t tried to encourage Kathleen and me to partake of his Ginseng I wouldn’t have known about that odd little prop either. So, if you can, visit your set(s) before the shoot. You’re bound to spot some props/vistas/possible shots that will enhance your movie.

Also, when you familiarize yourself ahead of time with a space in which you’ll be working, you may learn about certain loud-noise activities nearby that could ruin your sync soundtrack recordings. When that happens, you can either forgo that location before it’s too late, or try to negotiate with whomever is making the ruckus. Get their assurance that for a small payment they will refrain from noise-making between the hours of...(give definite times you’ll be there). Get owners of businesses and property to sign a Location Release as well, just to have something on paper – I ask people to write, “Received $20 ($50?),” and to sign or initial, right there on the Release.

While it is nice to have a pre-production walk-through at locations, you can still be fearless enough to just jump into unknown locations and be equally lucky, get good results with a spontaneous flow of shooting as I did during Morgan’s Cake. If I hadn’t been ready to deal with unknowns, I would have missed out on two of the most important scenes of Morgan's Cake, both at Rachel’s parents' apartment – the bathroom scene and the “She’s pregnant” steak dinner. As a spontaneous DV moviemaker you need to be prepared to shoot at both planned and unplanned locations.

NOTE: Get signed Location Releases at each and every location you shoot. One mistake in this bookkeeping procedure could cost you dearly. You could either be forced to pay ransom $ to get permission later from a opportunistic owner , or completely lose the ability to include that footage in the finished movie.

Leon Kenin Rick Schmidt Morgan Schmidt-Feng

Shooting Eclair camera in Nick Bertoni’s backyard, Berkeley, CA. Photo by Kathleen Beeler

If you hire a cinematographer, he/she may try to elicit from you more information than you are ready to give. But it will be worth that extra pressure to know you will have assistance. Cinematographer Kathleen Beeler was present during this series of shots at Nick’s house and throughout the entire Morgan’s Cake shoot, setting f-stops, doing great indoor lighting, handling all the technical needs as my “quality-control expert."

If you’re like me, you’ll want to shoot the shots yourself, frame the compositions and direct the shoot from behind the camera. When you operate the camera yourself (with only technical aid from a DP) you’ll be in a better position to determine what feels right, making the scene- building and forming of workable cuts your first priority. I framed the camera shots, moved camera and tripod myself between setups, as I continued to design cuts, angles, and compositions on the fly, constructing the one-to-one sequences as I saw fit.

No cinematographer could have effectively done that kind of creative scene-building, dialogue-commanding dance for me, because I wouldn’t have been able to clearly define my intentions mid-stream, or effectively explain my intuitive insights. Just having someone bothering me between each take would have been a recipe for disaster – I'd easily lose my train of thought if I had to verbalize every move.

You can’t become a visionary without exercising your vision, literally. If it’s your story, backed up with shots that you composed according to how you see, and the footage is later edited with that same personal touch, you can bet that the final result reflects your vision.

————

"The conflict/resolution cycle is a powerful one for building a gripping story. Give your characters an Everest to climb and an ice stormtoderailtheeffort. Pileupconflictwhile offering new real-life information that is particular to your project." This advice is so essential to storytellers. And, it occurs to me, that it should be a clue to us about The Story we are telling with our own lives. Perhaps instead of resisting or fearing conflict, we might consider how valuable it is to our own Story.