Making a 'Showboat' remake for 10K–––– adding my "1988" to the past Hollywood remakes; 1929, 1936, 1951 (the one with with Ava Gardner). Plus 12 frogs revenge!

https://www.reelclassics.com/Musicals/ShowBoat/showboat.htm#:~:text=Based%20on%20a%20best%2Dselling,destined%20for%20silver%20screen%20success.

(Stories excerpted from “12 DEAD FROGS and Other Stories—A Filmmaker’s Memoir”

FINANCIAL RESUSCITATION (1975)

If there ever was a rebirth in my life, this was it. I could literally breathe again, after winning $9918 from AFI to produce SHOWBOAT 1988-THE REMAKE. Looking forward to a check for almost ten thousand dollars I floated about my little Oakland apartment feeling happy and unpressured for the first time in several years. I had been saved! Probably the only thing that had held my life together during those last difficult months had been taking care of my little kids. At any rate, suddenly the sun shone brighter, the water of the Bay Area winked more brightly back. I later learned that hundreds of filmmakers and videomakers had applied for the ten awards given by AFI that year.

Friend William (‘Bill’) Farley, who insisted I apply for the AFI grant money those 49 years ago is presently is preparing for his own important premiere of his newest feature documentary, I WANTED TO BE A MAN WITH A GUN at Richmond International Film Festival (screening Sept. 26th, 6:30PM)), so maybe there is something called earning ‘good karma’ after all!. With such poor odds I had been one of the lucky ones to get funded back at that crucial moment, so let me THANK YOU BILL (from the rooftops!) AGAIN!

As soon as I read the AFI telegram I called my mother to give her some assurance that everything was going to be OK. Then I called Palmer Lab with the news, letting them know I’d pay what I owed as soon as the big check arrived. I also alerted my patient landlord, who would finally receive $700 out of the funds, for seven months of back rent. With my ability to sanely function now restored, my mind started to re-activate again. I could suddenly focus, make plans, be responsible for my life.

When Farley suggested then, April-May, 1975, that I hire professional scriptwriters for the new production, I listened to him. After all, he had basically given me the grant! So, I hired him, along with his writer friends, Nick Kazan and Henry Bean, to help me figure out the story of Showboat 1988-The Remake (the full title).

When I met with the writers in my apartment to see if we could work together, I first gave them each an unexpected check for $25, just for the visit. I figured that they should know up front that I respected their time. And probably that’s what clinched the deal, with all three agreeing to write for the $250 apiece (what I could afford—the Palmer’s Lab got half the grant off the top, for $ owed for edit room rental plus processing/prints of A MAN, A WOMAN, AND A KILLER). In any case I was lucky to have scripting help from Farley and that of his friends; both Kazan and Bean eventually moved to LA and currently have received the big bucks to script Hollywood movies.

SHOW BOATING (1975)

While I awaited the big AFI check to arrive I reread my application form and started thinking about my new film. I knew it would be dedicated to presenting Ed Nylund’s real life, his story delivered in images and narrations. Over the years Ed had described to me how his life, which began with a happy childhood, later unraveled as a result of his father’s tragic bout with cancer, and other personal disappointments (his divorce, dropping out of the Manhattan School of Music in New York, etc.). I figured that Ed’s history could be presented in juxtaposition to the backdrop of people auditioning for a role in Showboat.

When I hired Farley’s writers I really wasn’t aware of my artistic goals for this film, so they were free to mostly go their own way for a while. They decided to focus mainly on making sense out of who the Ed, Dick, and Z characters were, playing off the original “Showboat” characters in the original story. And their writing definitely did help create a strong structure, invent valuable scenes, and move the film ahead. It took a couple of years stuck in the editing room to discover what I personally wanted to accomplish, which was to urge the viewer to take risks, be creative with life, leap into the unknown, follow dreams in spite of all logic.

BUS FROM HELL (1975)

On one occasion during this glorious and happy pre- production period, my kids, Morgan, Heather, and Bowbay and I were narrowly spared being involved in what certainly would have been a fatal accident. I had picked them all up from Lincoln School in downtown Oakland (a predominantly Asian school where their mother had transferred them with hopes of them receiving a better education) at the usual time of 3:30 PM, crowded them all into the cab of my 1939 Dodge pickup, and headed back toward my apartment on Hudson Street, about three miles away. While it had been a busy week for me, somehow I felt more relaxed that afternoon, and wasn’t driving around at my usual hurried pace.

Sitting at a stoplight a few blocks from their school, I enjoyed the special light quality of the air, that sense that change is coming (could it rain through the sunny skies I wondered?). It felt good to be reunited with my sweet kids, and I looked forward to spending some money on them (a movie, good food) now that I was solvent again. Wasn’t life wonderful?

When the light turned from red to green, I hesitated, didn’t immediately hit the accelerator pedal as I had always done thousands of times before. Instead of moving right out into traffic, I slowly took the gearshift in my hand and dawdled, not engaging the clutch right away even though I was already in first gear ready to roll. My right foot was on the gas as always, but it didn’t push down, didn’t want to get the truck going. Perhaps I was caught in something like a Sunday-driver trance. Before I could think another thought, or wonder why I was so lackadaisical, still sitting at the green light a full five seconds after it had changed (I checked my rear-view mirror to make sure I wasn’t keeping anyone waiting behind me), a city bus filled with people packed to the brim came barreling through that intersection at fifty miles per hour, passing by in a blur. How many guardian angels had it taken to hold my foot off the pedal that day?

CONCEPT ESCALATION (1975)

While Farley and friends were writing their first rough draft of the Showboat 1988 script (see example of their scripting in my 1988 book, Feature Filmmaking at Used-Car Prices, penned after I shot the three days of audition acts) the concept began to escalate all by itself. Before I could figure out who to contact to rent a small theatre at Walnut Street Park in Berkeley, someone recommended a very large and affordable space in San Francisco, called California Hall that, I was told, had been used on numerous occasions for auditions. When I discovered that I could rent the hall for around $1100 for the three nights I reserved it without further thought. That one decision turned the audition from an almost private affair into a city-wide event.

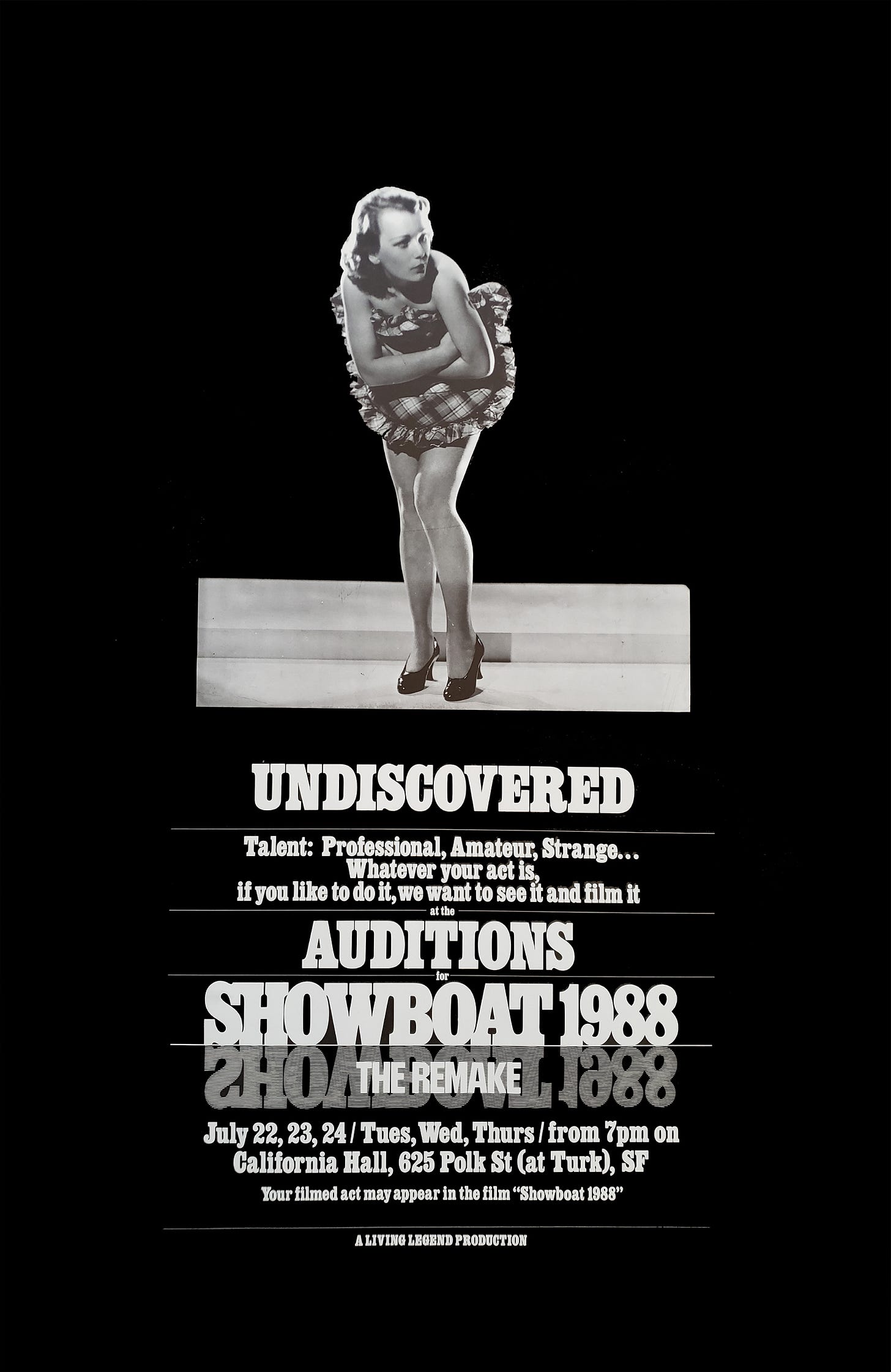

Then, during a conversation with Joe DiVincenzo, my advertising and art buddy from CCAC days, he offered to devise a poster, press release, logo, if I could just afford the $1,000 to cover his basic costs. I agreed, of course, flattered that someone of his immense talents would want to be involved. When I saw Joe’s huge poster paste-up for Showboat 1988-The Remake I was astounded. It looked so...real!

The poster read, Undiscovered Talent, Professional, Amateur, Strange...Whatever your act is. If you like to do it, we want to see it and film it, at the audition for Showboat 1988–The Remake. Your filmed act may appear in the film “Showboat 1988.” A Living Legend Production.

An advertising colleague of Joe’s had given him the idea to use the word “Undiscovered,” saying that everybody feels that way, unknown to the world. Joe seemed to enjoy putting his advertising skills to such a direct test, without any interference from clients. We were encouraging every talented, and not-so-talented (but ballsy!) showoff, performer, and on looker, to just stroll down to California Hall (Polk at Turk Street) and do their thing. If the poster worked we’d have a room full of auditioners. If it failed, it being the only ad campaign for the event that I could afford (except for a tiny 1” ad in the SF Chronicle), then we’d be sitting in the large hall all alone with a bunch of wasted film equipment. It slowly began to dawn on me just how big the event could become.

As I had for A Man, A Woman, and A Killer, I again went through the same Production Manager steps, reserving camera, hiring soundman Neelon Crawford from the first production, and a boom operator of his choice (pinhole photographer/artist Mike Mideke), ordering filmstock (I would shoot 45 400’ rolls of Plus-X Reversal 16MM B&W), adding a gaffer and grip for professional lighting duties. I would operate the camera again (isn’t this what real filmmakers did, I thought?). I figured that I could handle the added directing chores, because, after all, the performing auditioners didn’t need direction, just good recording of sound and picture.

When the first night of the audition finally arrived, July 22, 1975, at 6:30 PM, I can’t say that I was fully prepared for the event. It felt like I had bitten off more than I could chew. I sat behind a camera (mounted on a dolly) that I had shot only once before (my first feature shoot in Mendocino), and wondered if anybody would actually show up. As a strange tingling sensation began to spread in my gut, I suddenly realized that I was in the throes of a last- minute panic attack, and figured I’d better shoot something (anything!) before I lost my nerve. So, the first footage was rolled off covering a mock interview between feminist movie critic Constance Penley (of Camera Obscura magazine fame) and Ed Nylund. As I set Ed’s face in focus, that moment just before the job of shooting would finally obliterated all other concerns, I couldn’t help wondering what the fates had in store for me. What was my karma going to be? Would I finally have to answer for all those frogs I killed back at camp in the mid-1950s?

TWELVE DEAD FROGS (1955)

On the first day of camp in Wisconsin, running en masse with all my cabin-mates to get a required physical, I failed to navigate a patch of rocks and fell, my knee finding its mark on a particularly sharp and pointed outcropping. By the time I hobbled up to the nurse’s station, fifty feet further up the path, the blood had dampened my socks. She cleaned the wound, and told me that I was excused from all events at the camp until it healed. That meant, she enumerated, “no swimming, no boating, no horseback riding, no tennis instruction, no archery, no running of any kind” (pretty much everything the camp offered). So, I was set loose to do what I did best, wander around by myself, making up my own activities.

I could operate outside of the normal program as I had done for so many years around my own home in Chicago. I knew this routine. Mainly, I fished a good part of each day, starting off fairly soon after breakfast, sometimes even before that early meal if I wanted to dress up my eggs with some fresh northern pike or bass. I had an understanding with the cooks there that if I cleaned my own fish they would fry them up for me. I ate fresh fish numerous times during the seven-week camp stay. It took almost the entire remainder of my time at camp for my wound to heal.

At some point around the middle of this period of limbo, I watched as kids ran for the dock for the fiftieth time, yelping with joy before they made their dives into the chilly water, or chattering eagerly as they pushed away from the pier in row boats, and experienced a pang of pent-up anger and frustration. Why me? Why was I the one to be excluded from all the fun?

On a larger scale, why was my overall life so lonely? Looking down at my feet I noticed an infestation of frogs, who had come out of nowhere and taken over my nice little fishing spot. Unwanted guests would have to go, I thought. One by one I took each frog, set him (or her) on a flat rock, and threw another flat rock right at its head. After each victim was terminated I’d slide the carcass aside and grab another. Soon the beach was mine again. I counted twelve or so dead frogs, floating lifeless near the rocks. Now there was nothing to distract me from wallowing in envy as I watched the other kids having the times of their lives.

But the memory of those frogs didn’t wash away with their little bodies. My mind stored that black deed, held firmly onto it, way beyond all the particulars of camp activities I witnessed. How many cabins did the camp have near the lake? Don’t know. What was my counselor’s name? Not sure. What songs did we sing around the campfire? I have no recollection. But I remembered my frogs. Wasn’t I taught to be kind to dumb animals? (Yes). So where did I think I could get off killing defenseless creatures? (I don’t know). Would it have been OK if I had eaten what I killed? (What do you think?) What if I had handed the dead gutted frogs to the chefs of the camp kitchen instead of my recently filleted northern pike, requesting they add a platter of frog’s legs to my menu? Would that have made the guilt of my black deed disappear?

If there was one leather-bound book for each year of my life, and I pulled out the 1955 edition from the bookcase, all I’d find inside that volume would be a description of that incident on the beach, “The Story of Twelve Dead Frogs.”

The dead frogs were something I got to mull over as I grew older. At some point in my progression toward hopefully becoming a more sensitive, compassionate human, I realized just how hideously wrong-headed my frog killing had been. Maybe one step toward that realization was when I went hunting for the first time with my buddy John, in Arizona during University of Arizona days in the early 1960’s. We shot a few doves, he got two, I nailed one, and we returned back to my house, which I was then sharing with Mary-Ann, my soon-to-be first wife. As I proudly held my bird up for her to see, she shot me down, commenting, off-handedly, “Oh, I see you’ve killed a love bird.” How could I have killed something so innocent, a creature people associated with love and peace? John began to dispute this with her, saying love birds were a kind of parrot, but even I knew that the dove was a symbol of peace. I had just momentarily forgotten. I didn’t go hunting again after that. But I had killed some other living things before, I remembered. Something about frogs at camp.

Back at California Hall, I figured that if it was time to make a karmic payback for those frogs I killed, no auditioners would show up for Showboat 1988. Or maybe someone would interrupt the filming, confiscate the rental camera, tear down the posters, fine me for not getting a city permit for filming (or paying some union dues), and totally shut things down. But the frog gods were smarter than that. They wreaked their revenge in other, more insidious ways.

The frogs decided to let me continue filming – I shot over 100 acts on 45 400’ rolls of 16MM, charging processing and workprint (thousands of dollars) until my cash was gone, letting me spin a web of editing hell specially designed for my sort of person. Because of my Germanic penchant for precision – one cliché that seems to work…my need to find the best cut – how could I ever stop editing until I figured out the correct order of scenes? To do that I would have to suffer through a process of elimination. If you do the math you’ll see that if I were to reorder, in every way possible, the 100 separate performances I filmed at the Showboat 1988 audition, you’d learn that I’d have to try hundreds of thousands (millions?) of separate combinations!

And that’s not all. After all my torturous editing, when I finally completed my odyssey, finally got an answer print (in 1978), the frogs could sit back and sic MGM on me, along with the estates of Jerome Kern, Oscar Hammerstein, and Edna Ferber. These pillars of show business would threaten me with copyright infringement, lawsuits for violating their valuable Showboat-related material, basically insuring that my film (all my hard work) never saw the light of day.

Four years of artistic, monetary, personal and public hell, all for nothing. That had a nice ring to it, the frog gods thought. Inadequate punishment for gratuitously ending the life of even one of god’s creatures, but a start. Yes, let’s go with that Scenario.

Johnny Appleseed, the legendary American hero, who was actually a real person who lived between 1774 -1842, refused to kill any living thing, no matter what the consequences. It’s been told that one cold and snowy night, while John Chapman (his real name) was camped out somewhere in Ohio, he extinguished his fire when he noticed mosquitoes and other insects were perishing in the flames. Would you have spent such a chilly night without warmth, just to protect some annoying bugs?

I’ve reformed now, often spending up to fifteen minutes coaxing a spider who is stuck in my slippery enamel bathtub to crawl onto a piece of cardboard so I can carry him/her to the safety of the back door and beyond. Atonement feels good. Anyway, it’s a start.

—————-

That willingness to look for the "Lesson(s)," karmic and otherwise, in all the events you describe has served you well! I'm a firm believer that's exactly why we choose to have an adventure here on this planet.