Did some ART before I got into FILMMAKING. Here's first day(s) at California College of the ARTS (formerly CCAC, Oakland, CA).

(My "12 DEAD FROGS" memoir in paperback): https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0777FHXX2

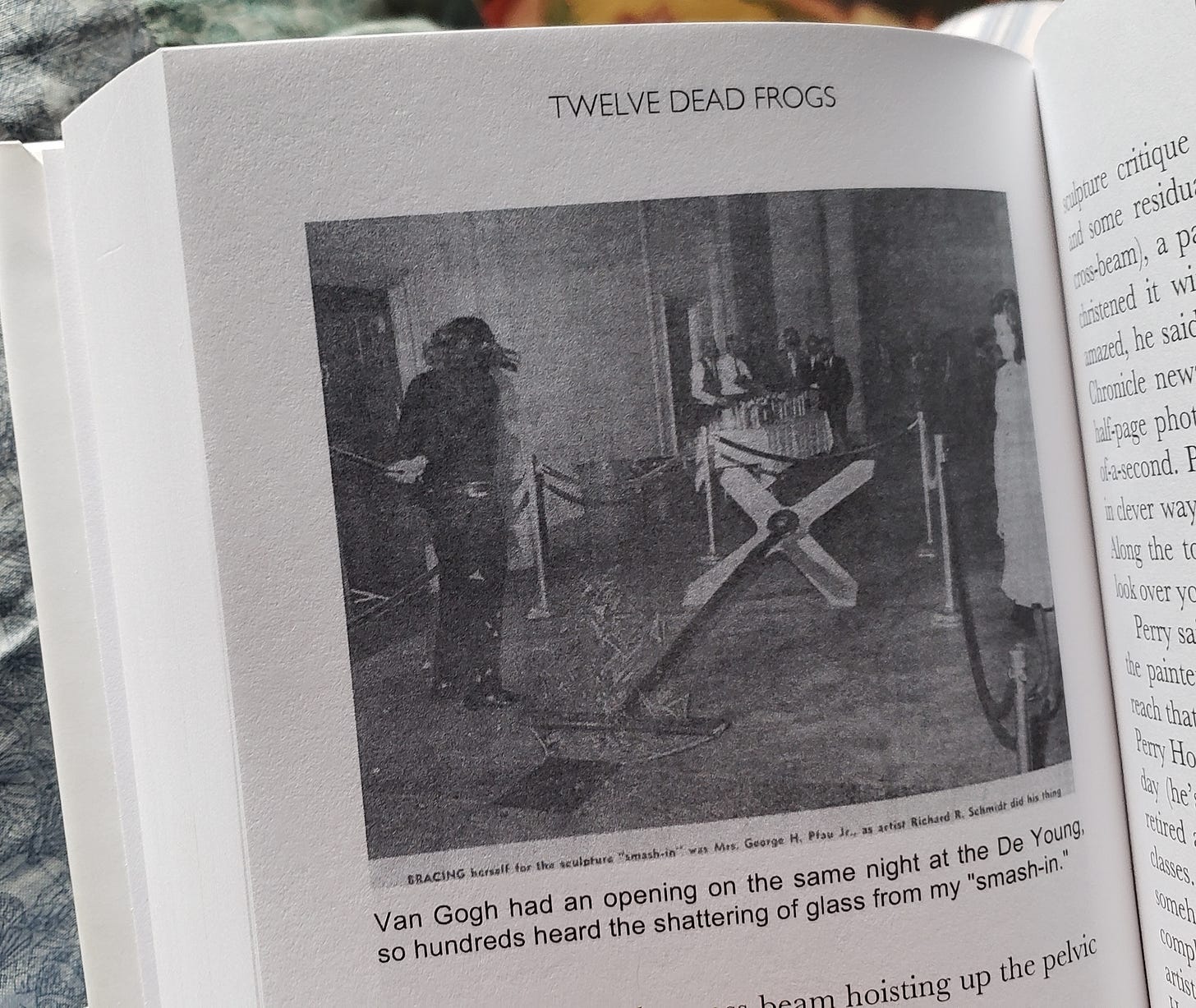

(Excerpted from TWELVE DEAD FROGS AND OTHER STORIES, A Filmmaker’s Memoir, by Rick Schmidt ©2017).

IT’S OWN REWARD (1965)

Joining the work force of low-paying jobs after quitting U.of Arizona in my junior year became another cross to bear. I found myself getting more and more frustrated with the menial job that had replaced my college education. The stupid boss at the Big Boy restaurant where I worked gave me nothing but petty complaints, even though I was trying hard to be conscientious. I knew that I was fast and efficient, having at one point during the midnight shift juggled the cooking of fifteen hamburgers, deep frying trout, poaching eggs, preparing salads, delivering other orders all at once without any backup. But all the boss had done was complain the next day when I created my own dinner while on duty, spotting me loading a plate with burger, cottage cheese, toast, an egg, instead of selecting a precise meal straight from the menu. Later that month, when I asked for a raise, he looked at me in disbelief, stunned as if I’d hit him with a punch. Basically laughing in my face, he said that he “could always get another Indian” to do what I did. But finally he relented, agreeing to raise my salary from $1.00 an hour to a still-measly $1.25 – not exactly a living wage, even for Tucson of 1965.

Sitting in the kitchen at home one morning, after working until 2 AM the night before, feeling groggy and generally pissed off at the world, I was handed a piece of paper by my first wife, who explained that she had done some research about art schools, and had located one called The California College of Arts and Crafts that I might want to attend. I hardly understood what she was talking about. She continued, saying that she thought since I liked to build things with my hands, and was also good at math, I might want to become an industrial designer. I hardly even glanced at the photocopied page before I crumpled it up, tossing the ball into a far corner of the room (I was a lot of fun to be around in those days!). She and the kids left the room shortly thereafter, to escape my obvious negativity.

Only later, after about an hour of stewing, did I get up out of my seat, walk over and retrieve the discarded scrap. When I unfolded it and read about the school, its philosophy of learning, I was surprised to find myself getting interested. Calling up the Oakland, California campus I was happy to learn from the registrar, Rose Rothchild, that even with my poor C- grade point average at University of Arizona, I could be admitted, “on probation,” until my grade point average came up to an acceptable level.

In a total reversal, I told her that I was now determined to go to California! She, of course, agreed, and we moved the family to Oakland a month later. Tuition was the affordable amount of $387 per semester, rents were cheap (we got an apartment for $80 per month), and I was back in school. Hardly any of the credits from my junior status in engineering at University of Arizona transferred over to CCAC, beyond a few basic math and English courses, but that was fine with me. I liked the idea of starting over fresh. For once I wanted to do it right.

PART 3

*****

ART AWAKENING

THE FUNNY STICKS (1966)

The first moments of art school were disorienting, to say the least. Suddenly I was sitting in a large classroom with kids much younger than myself, who were fresh out of high school. I was the grand old man of twenty-two, a father with two kids from my wife’s first marriage. One teacher, Mrs. Murelius, a woman of about sixty, explained to the class that she was tough and didn’t tolerate any “funny business,” so we’d better pay attention or she would flunk the whole lot of us! Hearing this was especially frightening, considering that I had half of my Freshman units (9 units) tied up with her studio classes.

I had just jumped into the fray, and without having come through the usual ranks of high school art education I floundered. While all the other art students in the class nodded their heads as the teacher spoke about Space, Texture, Form, Line, Content, I sat there stiffly, not understanding, but not wanting to reveal my ignorance. I was scared that once again I would prove to be the dumbbell I knew so well from a lifetime of screwing up. So it was nerve-wracking. To compensate, I studied hard, spent long hours on even the dumbest assignments, trying to be a good student. But by the end of the first month it appeared that no amount of commitment would help.

After assigning an art exercise, Mrs. Murelius would roam the classroom, chatting with each of the twenty or so students individually, to comment on their progress (or lack of such), finally arriving where I was seated. I dreaded her repeated focus on my work, still not understanding the positive impact a great teacher could exert on a hard-working student such as myself. The breakthrough moment for me occurred sometime during the second month at CCAC.

When she assigned us a project consisting of honeycomb boxes filled with some kind of repeating icon, each student had to construct a framework and bring them to class the following week. Mrs. Murelius explained that we should use the three hours of studio time to fill each little cubbyhole with some creation – a circle, a figure, something that could be varied, repeated in each small environment – and then turn in the results for grading. But I wasn’t getting any ideas! When Mrs. Murelius arrived at my desk and asked how I was doing, “Not well” must have been my answer (I was fiddling with two pieces of balsa wood and not getting anywhere). She encouraged me to just place them into one of the compartments and play around. While she stood there (more pressure) I placed the two pieces together, one in the foreground, one behind, then kind of fanned them out, wedging them against the top and bottom so they held their places. Then I made some subtle adjustments in the sticks while both of us eyed the little 3” square compartment. Suddenly and unexpectedly we both broke out laughing. The pieces had momentarily come alive! Just two sticks, one thin, one ‘fat’ – think Laurel and Hardy – had taken on some funny qualities, to which the two of us responded simultaneously . I’m sure that everyone in the class looked over at us, but I just remember her beaming face. That gruff old teacher had melted before a couple of little wooden sticks stuck in a box. We recovered, exchanged knowing glances, and she moved on to the next student down the way. She had worked her magic. And for the first time in my life I had a mentor, someone who would help me keep on course.

TYPICAL TWENTIETH CENTURY (1967)

Up until my second year at CCAC, when I first signed up for a foundry class taught by sculptor Charlie Simonds, my hard work at art had accounted for a good grade point average, almost solid “A.” But Charlie didn’t give a shit about hard work. He wanted to see good, world-class sculptures, that’s all.

He was a recent graduate of University of California’s MFA program, a hot-shot disciple of legendary sculptor/ceramicist Peter Voulkos, ready to kick ass on the art scene, make a name for himself and also hopefully survive teaching a bunch of weenies at CCAC. When I showed Charlie the first sculpture I planned to cast he blurted out, “Typical Twentieth Century,” and told me to try again before committing to metal. I spent the next week melting wax, sticking pieces together, cutting and molding, scraping and finishing until my sculpture was “perfect,” but he shot it down again, saying, “It’s been done.” I left school that day confused, defeated, vowing never to return. Because his class was nine units, half the entire load of credits I carried that semester, I knew a failure here would surely mean academic disaster.

Reverting back my failure-mode operandi, a routine I knew well, I unofficially dropped out of school, stayed completely off campus, mostly just hung around the house. I have no idea what my first wife thought was happening during this time. Perhaps I made up some excuse. I would have done my best to conceal the truth for as long as possible.

After a few weeks, I converted a vacant children’s playhouse in my back yard into a usable art studio (it accommodated a six-foot-high person with its peaked roof and 7’ square interior, and already had handy waist-high wraparound counters), and started playing with an old, half-circle wooden mold that I had purchased at a recent garage sale. I filled it with hot molten wax and let the material cool and coagulate to about a 3/16" thickness, creating some half-tube shapes. Then connecting them by melting the surfaces together, I made two identical undulating forms, wiggly like a snake, that I thought could be poured as aluminum. I figured that I could connect the two metal pieces to similar sized half-round wooden sticks, two inches in diameter. I could then finish those surfaces with spray paint, to create some sort of trapezoidal wall-hanging or floor piece.

Returning to the foundry one day, I proceeded to start ramming up the half-round forms of my tube sculpture, compacting special metal-casting sand against the hollow wax forms. By ramming sand against both sides, then removing the tube pattern, I’d have an exact cavity for replication in metal. In the midst of this activity, Charlie Simonds, happened by. He asked what I was doing and I explained. Slowly he got a twinkle in his eye, exclaiming, “Not bad!” and then said, “Want to be my TA?” (teaching assistant). By the time I finished n additional four sculptures that were part of that series I’d received a full tuition scholarship and was heading to a MFA degree.

Charlie had inadvertently pushed me through another ring of fire, made me see that hard work in art wasn’t enough. You had to understand the true worth of your effort, be knowledgeable enough to not repeat what had already been accomplished (and accomplished well) in the history of art.

AVOCATION (1967)

What had started as a well-defined educational pursuit toward an industrial design degree (dreamed up by my wife according to her assessment of my manual dexterity and engineering skills back inTucson) had now become something far different. Mrs. Murelius and Charlie had opened up my eyes to the idea of Art in the grander sense. What I had stumbled upon at CCAC was not, in fact, a career in a commercial art field, but a return to my own passion to create, which I always had as a youngster back in Chicago. CCAC had gotten me back on track.

My book on work done at CCAC.

"12 DEAD FROGS" available in paperback):

————-

"Mrs. Murelius and Charlie had opened up my eyes to the idea of Art in the grander sense. What I had stumbled upon at CCAC was not, in fact, a career in a commercial art field, but a return to my own passion to create, . . ." A passion that clearly continues to burn . . .

This is so interesting! I love the story of your mentor/mentoree experience in art class! Even the smallest of moments can have such a profound impact, and can change the course of our lives.

Now to continue reading…