(COLD/Posting #7). For full story see paperbacks & hardcovers: https://www.abebooks.com/book-search/title/cold-1918-19-siberian-escape/author/rick-schmidt/

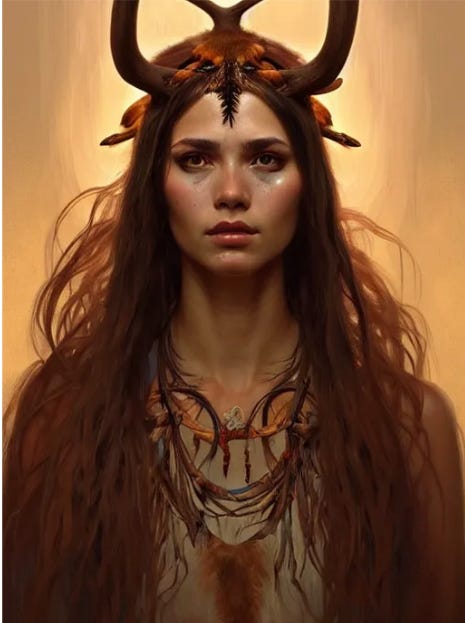

A young shaman from Siberia (above)––a bit of sensual spark in her face like I imagine Nanra has in the story, that attracted Captain Ewald Loeffler and returned him, temporarily, to the land of the living.

Here’s back cover of COLD again, just to keep the story in focus:

<https://www.abebooks.com/book-search/title/cold-1918-19-siberian-escape/author/rick-schmidt/>.

——————

Day-six finds Ewald getting a better daily rhythm to his efforts of travel, which is good because several difficult challenges await. The SIX PREDICTIONS that Nanra wrote down and sent away with him, become crucial to his survival.

—————

(COLD/Posting #7)

Later, after I had packed up my tent materials, the pole and assorted tools, I couldn’t help wondering if a wolf might be smart enough to wait silently at the backside of my tent. Surely one could have sprung at my head as soon as I revealed it. I made a mental note to consider cutting a tiny hole in the fabric when I camped again that night, so I’d have a peephole for checking for wolves from the back. If I carefully sewed some thread around the hole, embroidered it a bit, then it wouldn't risk a split in the fabric. Yes, of course ”N” supplied me with that too!

Day-six walking went well, with legs and calves falling into a good rhythm. Within an hour, my whole body was singing the same song: I’m stronger now, I'm stronger now, I'm stronger now. Just as Wife had predicted, day six was going to be a special and magical signpost for me. In fact, she had added that six was an important numeral for my entire journey home. She had enjoyed writing the numbers on paper, smiling and flirting, trying to communicate her thoughts to me those many days ago. Here’s what she diagrammed:

Five sixes equaled a month’s time, plus or minus a day here and there.

Two times six – thinking months – equaled a year. One and a half times six was nine...when our baby would be born. So I would pay attention to any ‘six’ as I continued my journey.

Nanra had told me that she would speak to me “through the air” as I walked along, and I had hoped she could accomplish that kind of magic. She said she could time-travel too, that she would swoop in and give me medical attention if I needed such a thing. Could that really be true? When I had questioned her psychic abilities, she had been quick to answer in a mix of tribal language (which I was beginning to better understand) and odd Russian phrases.

You'll know it when you see good results.

I knew her love-magic was strong. It had propelled me off my feet and into her cabin and salvation, before spitting me out two months later. I had been educated, loved, fed and spun around six times six before heading toward Germany. Anyway, she reinforced the importance of sixes, and told me to use six-something if I ran into any kind of trouble. She had given me a letter in an envelope, which had six predictions (she said I’d understand the drawings...). She had my promise to not open them unless I’d lost all energy or hope of going on. Only at that desperate moment should I tear off the corners and look. They were folded up in such a way, accordion-style, that I'd be able to see only one prediction at a time. Her order was examine just number one. See and absorb. It would be important magic for me. I could still survive, she said, if I truly understood each one. But I must entertain them in order, she cautioned, further explaining that to treat them lightly or frivolously would dilute the power.

Six predictions were like an extra six bullets – even stronger she said. They could build a bridge, provide food, repair frozen feet. They were real. So don't waste them. I still had all six. For all of the sixth day I felt stronger. And the weather seemed milder. It was a nice day of ‘No’s.’ No wolves. No people. No dead bodies and no second tree. No snow falling.

The sun was a faint glowing sphere above the cloud cover. The crunching of my feet against the ground sounded musical.

CRUNCH...then an intermittent, softer crunch. One leg sounded louder than the other. CRUNCH, crunch. Heard the difference. At least I thought I did. The moment of impact where my feet touched the snow seemed basically the same for both feet. After looking down for several steps I quickly refocused out ahead. I realized I was hypnotizing myself by staring too long. And that was dangerous. I looked right and left and spun around. To my great relief no wolves still.

OK. But what about the sound of my steps? I couldn’t imagine that my shorter leg, the one that had been set imperfectly by doctors in a Russian hospital during imprisonment, was making that much softer a step. Maybe I heard the crunch incorrectly. That is, maybe my ears were somehow working differently, one hearing better than the other, or the wind on one side controlling how I heard from that side. I tried taking a few steps directly into the wind and that suddenly equalized the sounds of my footsteps. This little diversion, though trivial, taught me some lessons about how to analyze my health and physical movements.

I realized that I had learned my Nanra-lessons well. My lover had told me that every so often I needed to take stock, analyze both my supplies and my strength. If I got too weak I could spiral into ill health, and ultimately cause my own demise. And the same was true about my drygoods. If supplies ran out before I restocked food, fire starter brush, and other necessities, I would suffer horribly. So, after my little self- generated crunching analysis, I set about mentally reviewing all the various items in my pack and belt, beginning with food.

My dumplings needed to be replenished. Six gone and eight to go. At the halfway point, seven gone-seven to go, I knew my emotions would start to drift into worry. As soon as I had five, four...then three and so on...it would be a countdown to starving. So while I was on the better side of pelmeni, not being as yet half-gone, I started to intensify my hunt for roots, following Nanra's well- repeated instructions for where to dig food in the frozen tundra. The drill that she had supplied had at least two main jobs. While it was mostly used for securing my walking-stick/tent pole, it must be used, she said, for drilling down to roots. Somewhere underground there was edible food, she promised, and I would need to dig something up to survive. She explained that edible roots were located close to the surface. Their sprouts grew up toward the surface in their search for nutrients, water and sun. While sunlight was denied them during deep winter, they still positioned themselves to punch through the frost at first opportunity. Look for tiny hairs of vegetation, she said, which can be felt above ground. By ‘hairs’ she meant the fuzzy growth off of the roots. She said I could identify them from a sample drilling. So, I'd just continue to take some samples as I walked along.

Around noon I stopped for my daily pelmeni, which, by then, had defrosted enough to be placed in my mouth. Paying heed to Nanra’s advice, I kept a second frozen pelmeni in my outer garments. It would stay frozen there, to toss out on the ground near my mini-tent if wolves attacked. That small snack could temporarily divert the wolves, giving me time to regroup. That was her theory anyway. Nanra believed that wolves were reasonable beings, and that they might even understand that I had offered a treat, and that they'd acknowledge that act by leaving me alone.

Wolves, she further explained, had many similarities to humans. There wasn't an overt meanness to them. They were just being good providers for their families. If I got myself eaten, she said, I would be feeding an entire wolf pack. Nothing personal. Parent wolves were responsible for the pack’s survival. My job was to make sure the wolves found something or someone else to feed on.

After a noontime pause, and small meal of pelmeni, I drilled my holes. (No turnips were found). Again I started walking. Snow was falling lightly, which seemed to warm the air a bit. Sometime in the afternoon the snow increased in intensity. I was suddenly walking in a full-fledged blizzard. The sun was blotted out and the air had taken a sharp dip in temperature. Cutting my day short, I searched for a spot to set up camp. I caught sight of a rise in the elevation and headed that way. Getting closer, I spied four animal hoofs sticking out of the snow-mound. I'd come across a horse or perhaps a mule. In any case, I approached cautiously, making sure no wild animals were feeding off the carcass. I did a wide swing, checking the back as well as the front. No carnivores in sight. With my gloved hands I pushed off the snow cover to see if any of the meat of the animal had been eaten. It didn't take long to see that the legs were still intact – the most overt targets of hungry quadrupeds. The main body was frozen under more ice than I could easily remove, and seemed untouched. How, I wondered, had wolves missed this large meal? In any case, the frozen legs offered little flesh for my future diet.

Night descended, and I followed my procedure of drilling a tent-hole for my walking stick, this time placing it right next to the body. I then spread out the tarp and secured the tent pegs around the edges. Once the sides were anchored, I threw loose snow over any gaps and loose-laced up the door. Thanks to the animal's large body, my tent seemed roomier than usual, taller at one end by about three feet. Where would I have been without my tarp and my ropes?

As I reached the halfway point with the dumplings (7 left, counting the one in my outside pocket as diversion for wolves), I had a fleeting thought about death. Yes, I had lived with death as ‘my mate’ for most of the war. From the first bullets that tore into my flesh to the Russian hospital, operations and healings, and the walk to Siberia, death was there. Two-thirds of us met their deaths on the trip to the camps. Anyway, it was time again for me and death to have another of our conversations.

Death reminded me how I’d been spared upon numerous occasions when he had taken the lives of most around me. Was I not well treated, he asked? Was I not the beneficiary of his great patience and kindness? Would it be unfair to take me so early in my Siberian journey? Well, my answer to myself, my mind playing both the parts, was, fair’s fair. I acknowledged that to have come this far was a miracle in itself. I had been gifted so many more times than any cat. So should my life now be snuffed out by coldness? After the weariness of so much walking, and the dangers of the wolves and lack of ready food, was my time now coming close?

How much time I gave to the play of words with death I cannot tell, but it soon switched to mere reminiscing. As I sat there in my little hut, protected against the strong winds and snow of a blizzard, a small fire blazing, I remembered early life in military school. Images of my parent sending me off to military school at age ten came to mind. At that time, I had figured that my mother was punishing me for making too much noise around the house. The memory of my father’s slap struck me again. That was my lesson. No familiarity or kindness from that man. What was the matter with him? Why was he so mean to me, while granting smiles and hugs to my older brothers? Suddenly I knew the answer! In the cold and difficult situation in which I found myself I suddenly knew the answer. Because I was short (5’2”) and a bad student, I was a bad reflection on him. He was less than a perfect German because of me! I was proof to the world that he had defects. He wasn’t adequate. It wasn’t even about me, personally. I was just his scapegoat. I was his whipping boy – prugelknaben. He reacted so violently towards me because he couldn’t afford to be found out himself, as an inferior German man. My failings were his.

He tried to stamp me out. Well, it didn’t work.

7.

Morning light came streaming in through the front laces, powered by a clear sky. I was happy that my memories of childhood hadn't made sleep impossible. The night had been cold, but the small fire between the hooves of the dead animal had warmed my tent. As I carefully unlaced the doorway and peered out, I was relieved to see no animals prowling about. I was also happy to see that the frozen dumpling I had tossed out as a kind of bait lay untouched. Emerging carefully, looking behind me in case a cagey animal was lurking, I stood up stiffly and walked over to my pelmeni and re-pocketed it. Far off, I could see wind swirling around, dry snow forming into a funnel shape. Fortunately, where I stood the wind wasn't hitting yet. I packed my tarp, bundling it into my pull-sled, loaded the rest of my supplies and started walking south. Lucky-seven was off to a good start.

(To be continued…)

(COLD/Posting #8 next)

I really love how Nanra is serving as his Guide, from "The Other Side."