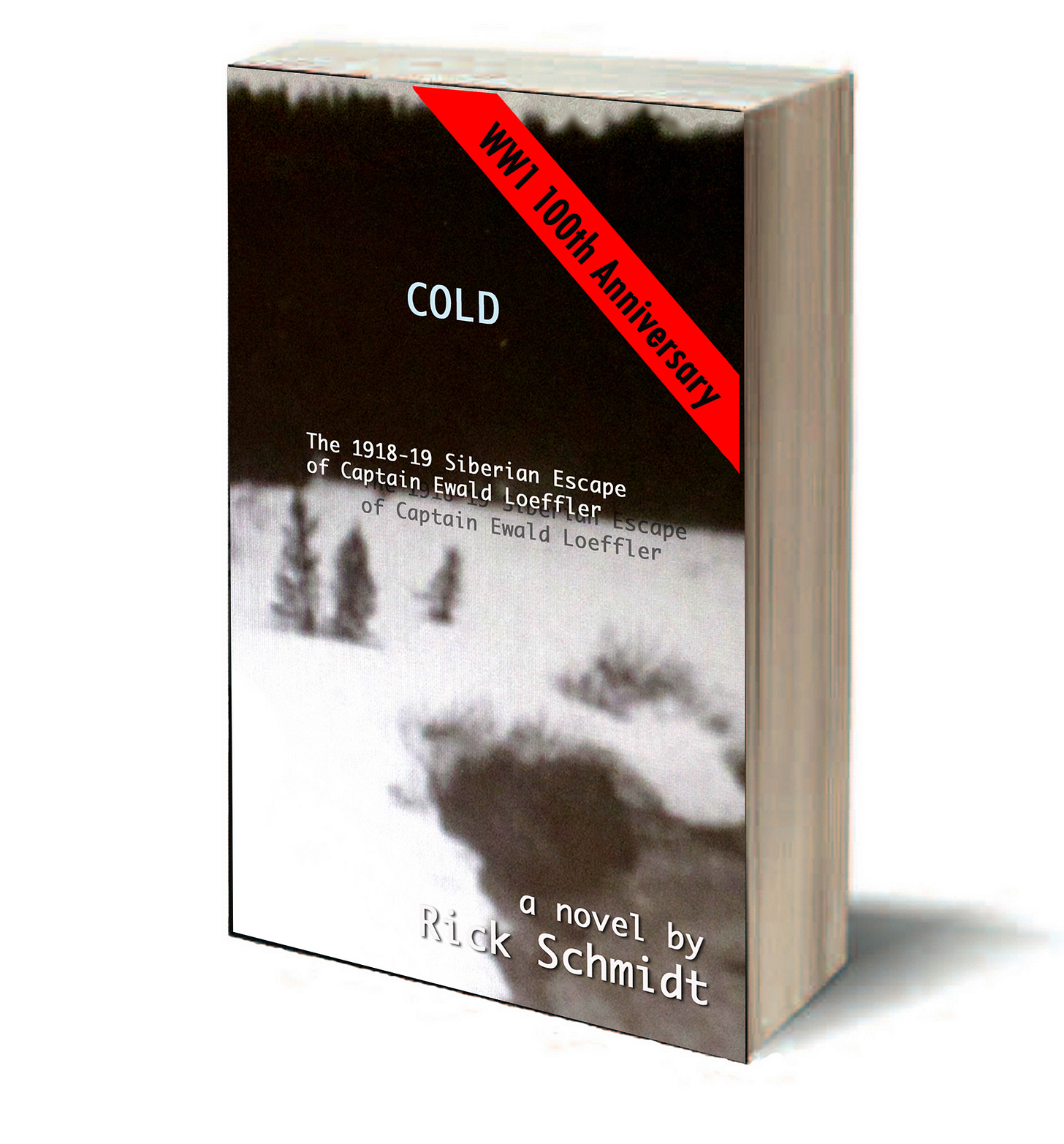

"COLD, THE 1918-19 SIBERIAN ESCAPE OF CAPTAIN EWALD LOEFFLER." Daily posts of my father, E.F. Schmidt's escape from a Siberian prison, WWI–what I IMAGINED happened on his 2-year trek back to Germany.

https://www.amazon.com/1918-19-SIBERIAN-ESCAPE-CAPTAIN-LOEFFLER/dp/136643787X/ref=cm_cr_arp_d_pl_foot_top?ie=UTF8 (if U can't wait for my next chapters!)

https://www.amazon.com/1918-19-SIBERIAN-ESCAPE-CAPTAIN-LOEFFLER/dp/136643787X/ref=cm_cr_arp_d_pl_foot_top?ie=UTF8

Dear subscribers, hope you are ready to read some postings from a couple-hundred page FICTION WORK!

As a soldier who was captured by the Russians, my father, Captain Erich F. Schmidt, spent 4 years in a Siberian prison camp. then endured another 2 years traveling through Russia toward home. My mother told me that he had to impersonate a White Russian one day, a Red Russian the next, and in either case he could have been killed on the spot if he got that “acting job” wrong. As a German soldier he was hated in Russia, which made it a perilous journey; the odds much against him surrounded by foreign enemies, and dealing with the deadliest foe––brutal Siberian weather.

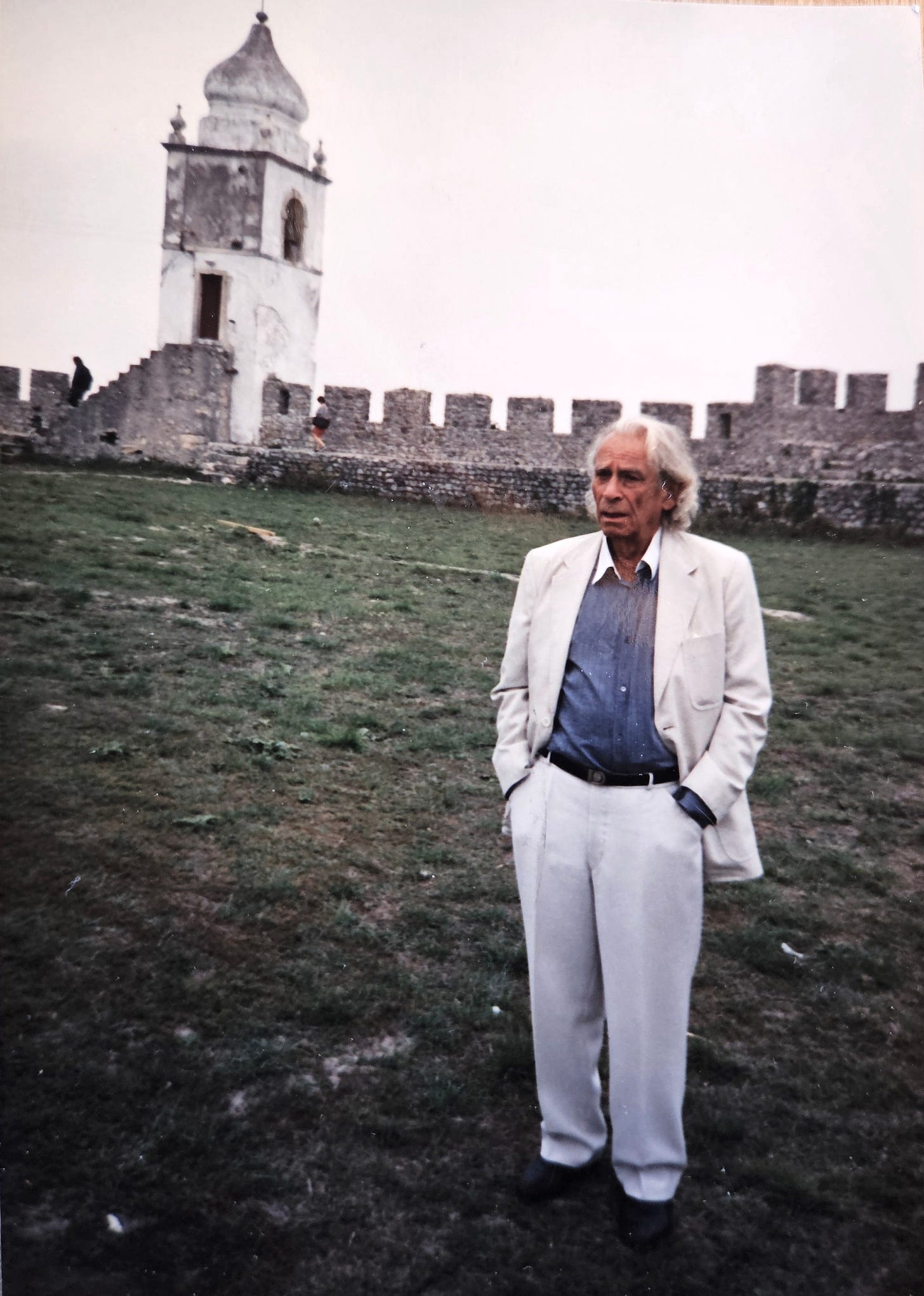

When the prison guards decided to join the Russian Revolution in Moscow they just disappeared one day, leaving the inmates to fend for themselves. And that is where my story begins. And pardon me for name-dropping of a famous person, but when I attended the Figueira da Foz International Film Festival IN PORTUGAL, 19992, for my feature AMERICAN ORPHEUS, I was befriended by about the only other American there, legendary writer/director Sam Fuller (<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Steel_Helmet>, etc.). He attended my screening and then was very attentive and listened to me as I related this a story about my father’s WWI experience and capture by Russians (this book!). And while we sat together on a park bench near the beach, he gave me some advice; here’s what he said (I wrote this up in the 2000s):

“In 1992, I recounted my father’s Siberian story with the legendary writer/director Samuel Fuller (The Steel Helmet, The Big Red One, etc., <http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0002087/>), when he and I were among the few Americans attending Figueira da Foz International Film Festival in Portugal. With a friendly wave, and a salutary, “Rick!” he’d urged me over to his seaside park bench a few hours after watching my American Orpheus. Fuller proceeded to give me his Hollywood-hardened, combat-tested, WWII war-reporter’s advice on how best to script. These are approximately his words:

“Start it the day your father left [the prison camp,” he said. “And no battle scenes. Don't need ’em.”

He glanced over, to see how his words had played. “End with his mother’s words, and that’s it. You're done.”

It took about 20 years before I had the proper audacity to go for it, nicely distracting myself by making movies. To be exact, thats 21 features-worth of avoidance, mostly co-writing/co-directing/producing my 10-day, start-to-finish Feature Workshops digital flicks but with a few solo efforts thrown in (THE FIFTH WALL, NO TEARS FOR BANKERS, STICKY WICKET). Finally riding on the coattails of Sam Fuller’s encouragement, the resulting novel, COLD, (<https://www.amazon.com/1918-19-SIBERIAN-ESCAPE-CAPTAIN-LOEFFLER/dp/136643787X/ref=cm_cr_arp_d_pl_foot_top?ie=UTF8>), is what I’m posting. Hope you enjoy the ride.

Sam Fuller and my younger self, getting acquainted at Figueira da Foz Intl. Film festival, 1992, before screening AMERICAN ORPHEUS (<https://vimeo.com/ondemand/americanorpheus/>).

HERE’S THE BACK COVER OF MY BOOK, which may help to somewhat explain the upcoming novel and my personal journey writing it. Like the text says, it’s about a man, my father, who was, for me, a very hard person to know.

What I’m going to run here, on Substack, are short installments of the book, right out of “COLD,” that’s available on amazon and elsewhere, online and in bookstores in the US, Germany, Japan and the 11 countries that Kindle serves. Chapters will be released in order, and I hope U find the adventure an enticing one. Others have found it a “page-Turner,” and hope it is 4 U 2. Please stick with it and enjoy the next segments. Let’s see what happens! (PS. If U get impatient, it IS FREE on KindleUnlimited: <https://www.amazon.com/dp/B076VBJB62>. And the paperback doesn’t cost an arm or leg either.

A picture I took of writer/director Sam Fuller, who made some of the first and hardest-hitting war (anti-war) movies in the history of cinema.

Martin Scorsese once said of Fuller, "It's been said that if you don't like The Rolling Stones, then you just don't like rock and roll. By the same token, I think that if you don't like the films of Sam Fuller, then you just don't like cinema. Or at least you don't understand it.".

So, here goes: My first entry; Introduction and the beginning of Chapter 1. Subscribers will now receiving sections of my book, as if I dropped by your house, rang the bell, and handed you a next INSTALLMENT. Future chapters will arrive throughout this week, for several days in a row, until the weekend—a break for other subject matter. PS. For this book I changed my father’s name to “Ewald Loeffler,” but most all the basic facts are real, as related by my mother.

This is posting #1.

ENJOY!

——————

COLD

by Rick Schmidt ©2017

<https://www.amazon.com/dp/B076VBJB62>

INTRODUCTION—Lincoln, Nebraska, 1956.

During my years after World War 1, I only allowed myself to discuss the war twice, both times with less than satisfactory results. The first occasion was when I was deeply engaged in a chess game with a young man who had eagerly challenged me to that contest after his boss at the Archive mentioned I had an ancient set with ivory pieces. Not only was the man – call him Boris – going to have a chance to beat me, but he would also be able to handle the artifacts; pieces of king, queen, horseman, pawn, priest and castle. A good deal, he thought. About halfway through the four- hour game, trying for an advantage, he asked about the prison camp I'd inhabited for four years in Siberia, 1914-1918. He was bright; I'll give him that. Who had told him about my background as a soldier I do not know, maybe he'd read it somewhere, but his inquiry greatly disrupted my focus. Before I could protect myself, change the subject, he struck again.

He inquired further, asking whether I felt warmer or colder at that very moment when the guards of the prison threw open the gates and ran off toward Moscow to join the revolution. Yes, he diverted my thoughts, made me think back...to real war. But his tactic could backfire. As I regarded his tiny swords angled toward my queen, I suddenly toughened up. I was playing to the death again.

Was I warmer or colder back then? The Siberian winter of ‘18 was hovering around 20- below. How did I know that figure? The guards used to tease us with the numbers off their thermometers. Sometimes, when I felt it was a bit warmer than their reportage, I felt like saying, can't be that cold... can't always be -20, because they never quoted any other figure. At any rate, my brash young opponent had successfully jogged me back to standing in that Siberian landscape forty years before, standing there in newspaper- stuffed shoes, layers of rag coats, a makeshift hat and cloth earmuffs – hardly sufficient protection against the wind and cold.

I totally forgot the game. My plans for future moves and evasive actions, attacks at the weak points on his line suddenly disappeared. Was I warmer or colder? I couldn’t shake the question. Guards running. Open gates. Food scarce. No real belongings, and thousands of kilometers from Stuttgart. I had watched as fellow prisoners cheered and ran irrationally out of the camp...but to where? Eating what? Surviving how? As an officer, I guess, my mind worked more slowly, was naturally more deductive and structured. Less impulsive. I asked myself what I could take from the prison grounds to help me better survive the weather? What could I use to forage for food? Walking the long journey home would probably take years. Everything was extremely problematic. If I found food (and ultimately I did), how could I defend it from other men hell-bent on stealing it for themselves? Surely they would have beat me or killed me for my boots. If they ever got a chance I’d be hurt or dead. So I’d decided to slow myself down, get the best bearings before departing.

But back to the young Turk's question. Thank God he knew nothing of Nanra-naw and our life together after the camp. That would have sufficiently jostled me. That would have won him the prize. I answered warmer...the opposite of what I thought I had felt so many years ago. Why a wrong answer? I hoped he would be just a tiny bit confused, giving me time to re-focus on my chess pieces, regain my wits so I could be the grand adversary I believed I was. And ultimately I won that match. An important victory. And he never did ask me for any more reminiscences.

The second mistake I made recounting my past was when I told some war stories to a much- younger wife one evening, early in our marriage. After one too many bourbons, lips were loosened. Before I concluded by pleading tiredness, she asked me if my mind formed words and thoughts first in German, before translating back to English. Perhaps she believed that my pauses after each of her more-probing question were due to some sort of inner-translation. In fact, I was just trying, unsuccessfully, to fashion answers that didn't lead to more questions. You try it. Try to tell just the right amount of a fascinating tale so that your listeners don't demand more. Not so easy. Certainly the ones closest to you – your family – are the best interrogators around, better than any gulag goons. Do they not have the best, most effective torture methods available?

Anyway, the answer I gave, the final question I allowed about my past was this. I said that now I thought in English. I wrote, spoke, and even dreamed in English. And I only shifted into German when I was faced with a book written in that language, or when confronted by a German- speaker. Had I not been so abrupt – I walked my glass to the kitchen and rinsed it out – I'd still be answering questions to this day.

As I’ve mentioned, my fellow prisoners fled the camp; ran, walked, hobbled or crawled out from their various cabins toward the open gates, heading into the freezing cold in a perceived direction of their various homelands. And witnessing this desperation, watching their ill- conceived journeys unfold, I stood completely still, my eyes and mind never clearer. A frozen death awaited them – all of us. And I felt colder.

***

CAPTAIN EWALD LOEFFLER’S SIBERIAN MEMOIR 1918-19

1.

December 12, 1918

The day came up slowly, sun hiding somewhere over the cloud cover. A chill I'd been fighting all night seemed to have penetrated my bones, as well as the skin of my legs. I shouldn't have been surprised that the temperature inside the thin- walled labor camp housing was lower than usual, since there was no longer heat generated by my fellow prisoners’ bodies. Everyone else had left. So perhaps I'd just experienced the coldest night of my entire incarceration.

Until that day of freedom, the prison guards had issued orders on a daily basis and there was never a chance of stonewalling. And then there had been the fellow prisoners who had what seemed a desperate need to converse. Of course speaking among ourselves, discussing girlfriends, imagining familiar landscapes of German hometowns, sharing memories of meals our mothers cooked, made the time go by a bit more pleasantly. But by the fifth telling (the fiftieth), a person was happier to sit alone and feign sleep. I, personally, was tired of listening to others. So it was not an imposition to operate as a sole hermit when the camp evacuated. In any case, I chose to first collect my thoughts before leaving. So I found myself sleeping alone in the empty barracks. I was alone except for a few brown rats that scurried about the floor, searching for crumbs overlooked by my officer bunkmates.

Germany was over 5000 kilometers away. Or was it 6000? What was the difference? To walk either distance during winter conditions would probably be impossible in any case. But so what? That hadn’t seemed to slow anyone down. Prisoners ran out through those open gates the second they were deserted by our captors, all heading for Moscow to join the Revolution. Instead of continuing to take the kind of measured steps and actions that had ruled their existence since incarceration, prisoners had run in circles, crisscrossing the fields, opening doors without closing them, not stopping for even a brief second to acknowledge another person's presence. Only the pairs of male lovers stayed together. Men who were committed to deep friendships hoped that being part of that team would help, working together to survive the difficulties ahead. But mostly it had turned into a free-for-all. Every man for himself.

I rose from the stained cot and started my 'shaking-off-cold' exercises, a procedure that I’d repeated daily for the prior three-and-a-half years. As always, I began slowly, making a couple deep stretches toward my toes, reaching side to side using my outstretched arms as directional beacons. As on many previous morning I imagined myself a human lighthouse, peering out over water. My imagination filled things in. As I did sideways stretches swung myself around, my fingertips emitted beams of light. Yes, my imagined lighthouse was hampered by the density of walls in our prison housing, but I refused to accept such a harsh limitation. The walls might have seemed real to others, but to me it wasn’t so. I was a lighthouse, I had purpose, I could make a positive impact. I could save lives in seas around the prison camp. If need be, that is. I was useful. My life, thusly, had some meaning. Maybe that's why I'd been allowed to live until then.

I did other exercises too – shoulder rotations, sit-ups, jumping jacks, deep knee bends, curls – I wind-milled myself back to a functional body temperature. My exercises were the only heating system I had. Once exercising was completed it was on to finding food. As I had done for years, I compartmentalized the task. To make sure I wouldn’t miss even the smallest particle of food I mentally broke up the room into a grid, and checked each section thoroughly - surfaces of tables, chairs, bed, floor, initially revealed nothing. But that didn't mean it wasn’t there. I looked some more, bending forward, bringing my eyes even closer to things.

After an hour of searching in each section again I’d found nothing. When I stopped looking, I felt the chill come creeping back into my bones. It was very cold. And the wind was kicking up some. With no food to be found inside the kitchen area, I knew I must soon leave the safety of the camp, join my fellow escapees and start my journey. I took a final tally: (1) I’d exercised successfully. and (2) I’d hunted for food. Now it was time to (3) walk toward Germany and look for food along the way. Was this really different from what any other prisoners did or thought? They lit out toward Germany at the same time they were desperately looking for food. So I can’t argue that it was any different. All that they had done was leavethecampaheadofme. Ihappenedtohave another approach to the evacuation. I was slower. Who was right? Don’t know Maybe they were all dead by now. Or eating a lot of found food. I can’t really say.

I knew when I finally did leave I must be watchful for people who might try to kill me. White or Red Russian made no difference. There were Russians in the vicinity who may risk their lives to take mine. All were frustrated in some way, not really acting like themselves, and however peaceful they might first appear, they could turn violent This was common knowledge. So I would have to be extremely cautious of any strangers along the route. Nothing must escape my sight. I’d walk straight ahead, but occasionally also look backwards and to the sides. That would be my definition of ‘careful forward progress.’

Believe it or not, I remained in the barracks another night, giving myself one more chance to sleep in the camp. I was just not ready to leave. But my hunger was increasing. As I dozed off dreams drifted in – I was eating the pelmeni dumplings we German officers received once or twice a year from our Russian captors. Biting down on delicious dough-wrapped envelopes of vegetables and meat made us aware of the luxury of food. Yes, a necessity for survival, but also mouth-watering pure joy. My starving mind and body actually must have been grinding away on my tongue as I slept because I could swear I had devoured something that second night. I remembered arguing with a fellow prisoner about how the outside of the dumpling was thinner than other previously served treats. Was the dough shrinking, I asked someone? Were our captors shortchanging us in this method? Or were the cooks actually improving in their ability to serve up the common Siberian delicacy? Thin-shell pelmini were gourmet. Everyone knew that. Why would we be served gourmet foods unless they planned to execute us all the following daybreak? I got scared. That's when I’d been jolted awake to the empty, frigid and depressingly grey room of my incarceration, day two of my supposed freedom. Without a doubt I knew it was time to go.

(To be continued…)

I remember reading the book years ago, and I'm happy for the chance to read through it again. What an astonishing story ... and so well told!