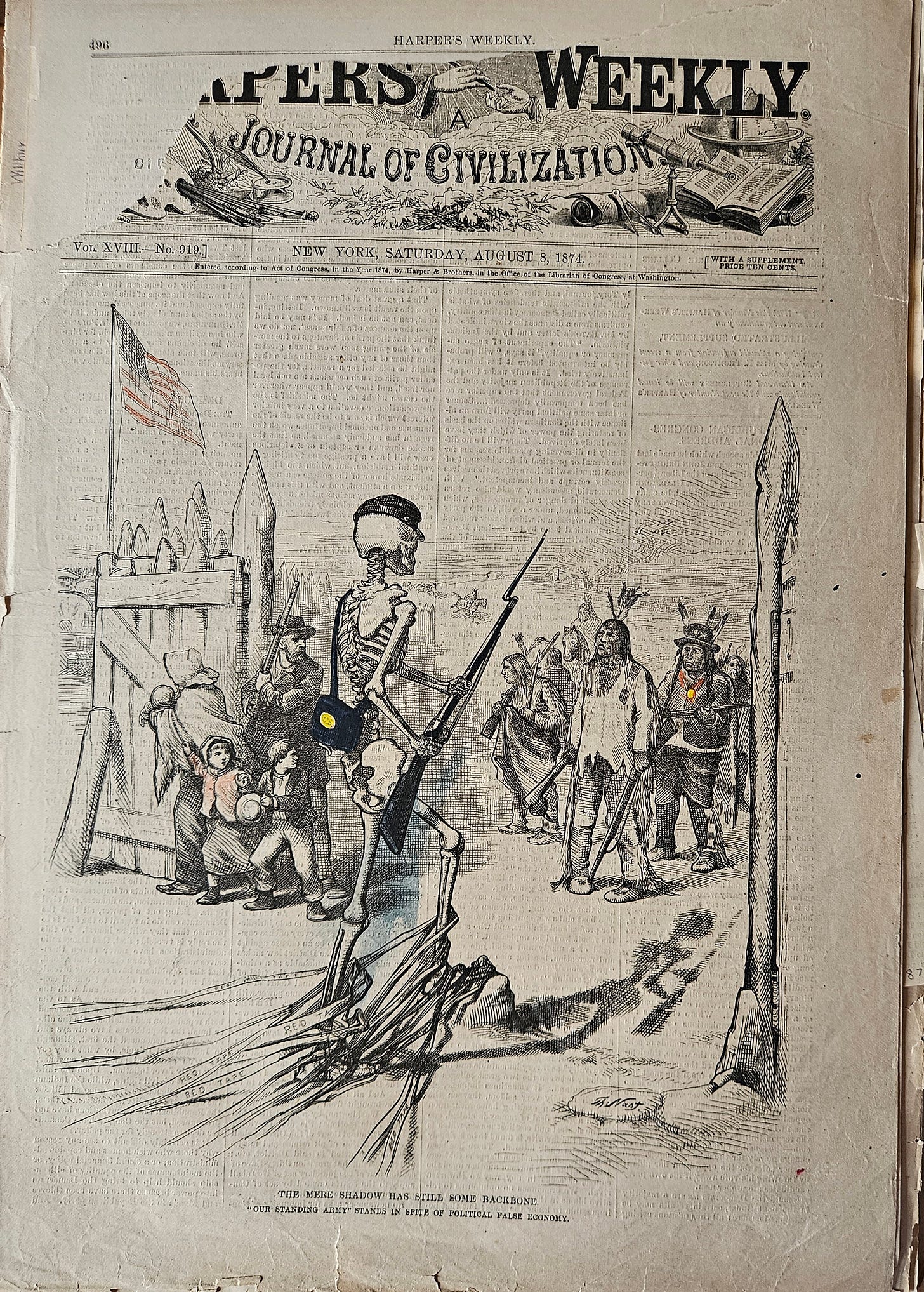

CIVIL WAR/Skeleton August 8, 1874, by Thomas Nast. (& more commentary From Nast's Grandson--after Harper's Weekly he was making paintings...).

THE MERE SHADOW HAS STILL SOME BACKBONE.

“OUR STANDING ARMY” STANDS IN SPITE OF POLITICAL FALSE ECONOMY.

Through these cartoons, Nast, a Republican and supporter of the military, ridiculed and condemned the Democratic Congress for even the suggestion of reducing the U.S. Army during an era of Indian warfare on the frontier. More specifically, these cartoons lampoon the House of Representatives bill, H. R. 2546, which provided for the gradual reduction of the Army of the United States. On May 23, 1874, Republican Indiana Representative John Coburn from the Committee on Military Affairs reported the bill. On June 1 the House passed the bill and requested the concurrence of the Senate. The bill was referred back to the Committee on Military Affairs.

Drawing for Harper’s Weekly between 1859 and 1860 and 1862 until 1886, Thomas Nast (1840-1902) was a caricaturist and political cartoonist of national renown. In 1873, following his successful campaign against New York City’s Tweed Ring, Boss Tweed and Tammany Hall, he was billed as “The Prince of Caricaturists” for a lecture tour that lasted seven months. He popularized the elephant to symbolize the Republican Party and the donkey as the symbol for the Democratic Party, and created the “modern” image of Santa Claus. Following his death he was attributed the moniker, “Father of American Caricature.”

* * *

More from Nast's grandson (AMERICAN HERITAGE; “The Life And Death Of Thomas Nast”)

My earliest personal memories of my grandfather relate to the many times that I visited the Morristown home in the years just before and after the turn of the century. I was fortunate in being a favorite of his as a boy, no doubt because my mother, Edith Nast, was very close to her father and I was his eldest grandson.

Following the publication of his Christmas Drawings for the Human Race in 1890, my grandfather spent a great deal of his time in his studio at home, painting. He seemed to find peace and relaxation in quietly working on his canvases. The days of the crusading cartoonist who sometimes dipped his pen in vitriol were past. Thomas Nast, the painter, was a gentler person and the only one that this grandson ever knew.

Most of my grandfather’s paintings had to do with Civil War subjects, many of them based on sketches he had made on the scene thirty years earlier. His huge canvas showing New York’s famous Regiment marching down Broadway on its way to war in April of 1861 and his Peace in Union painting depicting the surrender scene at Appomattox four years later have been widely reproduced and are recognized for their historical accuracy. Ina different vein was his Immortal Light of Genius , a tribute to William Shakespeare, a replica of which hung in the Shakespeare Memorial at Stratford-on-Avon, England. It was stored during enemy bombing attacks in World War II but was, unfortunately, irreparably damaged. Thomas Nast’s Head of Christ , acquired by J. Pierpont Morgan, was loaned by Morgan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York City, where it was once shown. See painting here:

Had Thomas Nast followed his early aspiration to become a painter, he might well have earned recognition in that field rather than as a cartoonist. As it was, his training was not such as to gain him the reputation in the field of art that he was to win in caricature. Critics have acknowledged that his paintings, while they appear labored, have a heavy power and deserve more recognition than they have received.

Most of my grandfather’s paintings were commissioned by old friends; and while payments were liberal, income from this source was insufficient to support his family.

During his painting years the artist often hung his paintings next to a large window to dry in the sun, sometimes upside-down or sideways. Included among these were his self-caricature and his head of Christ. On one occasion during this period the delivery of my grandfather’s daily paper was suddenly discontinued. Upon complaining to the distributor, he learned that the young boy who used to deliver the papers had seen what he thought to be strange people looking out of the window. The paper boy concluded that the house was haunted; and when he finally saw the Lord himself peering out of the window, he was definitely through and would deliver no more papers to that house!

Of course, I was not old enough to appreciate that my grandfather was having financial problems; but I later learned that it distressed him that he was unable to be as generous to his family and friends as he had been during his more affluent years.

I recall Thomas Nast as a relatively short man, perhaps five feet six or seven, always impeccably dressed in dark jacket with boutonniere, waistcoat with gold watch chain, a stickpin in his ascot tie, and gray striped trousers such as worn with a cutaway. He was very distinguished looking with his gray hair, which was always tousled, his Vandyke beard, and flowing mustaches. He wore a wide-brimmed fedora and carried a silver-headed cane, which he often tucked under his arm as he strode along. There was something of the actor in him, and he was, in fact, a member of The Players, a club in New York whose membership roster included most of the leading actors of the day, as well as some artists and musicians.

My grandfather took me to the club on several occasions, but I cannot say that I recall any of the stage celebrities I met there. Strange as it may seem, the character I most clearly recall from one of those visits was the traffic policeman at a busy intersection nearby. The officer tipped his helmet and greeted my grandfather by name as we crossed the street together, whereupon we stopped in the middle of the crowded thoroughfare as I was introduced. A very proud moment!

From time to time my grandfather took me to the theatre or circus in New York, and on one such occasion I recall going backstage to meet the famous actor Joseph Jefferson, who played Rip in Rip Van Winkle . I was even more impressed that Buffalo Bill was a friend of my grandfather’s. I can still recall the shooting of the cowboys and the yelping of the Indian warriors in Buffalo Bill’s exciting Wild West show. And I remember seeing Annie Oakley shoot clay pigeons from every conceivable posture. The show was presented in Madison Square Garden, and I wondered why the bullets from Annie Oakley’s gun didn’t kill some of the audience, not realizing that she used a shotgun, not a rifle. Tickets to most of the performances we attended together were free passes, known at the time as Annie Oakleys because they had holes punched in them, as though perforated by Annie’s shotgun.

————

Wow. Even Santa Claus!! It's hard to think of anyone, currently, with the kind of influence Nast had.