BLACK PRESIDENT, Chapter 26. Leon loses both his wife AND SONS (they move to Chicago). The worst of racism--TV coverage with the "N"word shouted by mobs of insane Alabama state troopers and locals.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a5w33oqL_sE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

January 14, 1965

Bela waited for the eighth ring before she hung up. It had been over two weeks since she’d heard from her grand-daughter. Sarah’s move to Chicago the year before had taken Bela completely by surprise, but with her daughter, Dee, agreeing to let Sarah and the twins move in the 49th Street apartment, Bela had grudgingly gone along with the plan. Sarah and Leon had not been getting along at all, so what other choice had there been?

“Chicago brings the twins a little closer to Washington, DC” said Sarah. “And that’s a good thing. That’s where they’ll end up anyway, when they’re grown men. So I’m just helping them get adjusted earlier to the Eastern part of...” she continued on with her seemingly irrational explanations, saying things that made no sense to Bela.

“Got to do what’s right for the boys,” had been Sarah’s pat answer to almost every argument Bela threw at her. “They need their father,” Bela had pointed out. Sarah silenced her with her curt response, “They don’t have one. He was assassinated.”

Leon hadn’t done any better in his attempts to dissuade his wife from making the move. He had been living with the weirdness ever since Kennedy was shot, dealing with his wife’s strange outbursts right through Christmas and New Year. She had kept on about “Kennedy’s twins,” until he had finally just walked out the front door. What could you say to a totally deranged woman?

During the year-long separation, the biggest question for Bela had been how Leon would hold up, losing both his wife and the two kids all at once. He may not have had much time to spend with the boys prior to the separation, but he loved them deeply. That much Bela had assured Sarah. But Sarah had left all the same.

Leon did not seem equipped for the bachelor life, thought Bela. In fact, he seemed down right depressed most of the time. If they had been a rich white family, he would have been sent off to some expensive psychologist for diagnosis and medication, she thought. Maybe they’d give him shock treatments or feed him some expensive pills. She’d seen programs about shock therapy on TV. They might have used those fancy electrodes to snap him out of his funk. Anyway, she’d watched as the fight had gone out of him. And now the kids hadn’t seen their father in over a year. Would they even recognize him? Probably not.

The night she left for Chicago, Leon had a long cry back in the garage where no one could see him. There, in the dingy bathroom, he had finally let it all go, weeping silently then hitting himself in the face for being so dumb, so inept as a lover. Boraxo soap dust covered the floor and the side of the grease-ringed sink, more proof of his negligence. The old, funky toilet gurgled, trying to say something, blame him for his rampant failures. Leon cried some more. He blamed his misfortunes on that fall from the roof. He just hadn’t had the mojo working right to keep his woman happy. That was it. He couldn’t get it up. And now, his sweet little sons were gone too.

Would he even be able to tell them apart next time they met? If something didn’t change he would miss out on their whole childhood! Time moved so swiftly. He blinked and a year had gone by. He knew he had to get out there somehow, move to Chicago himself, so he wouldn’t become a stranger like his own father had been to him. He couldn’t bear it for John and Jackson to go through that same kind of confusion.

Leon thought back to when he was seven and had tried to please his father. It had backfired horribly. He remembered cooking scrambled eggs for the old man, with his mother’s support. He carefully cracked the two eggs in a bowl, making sure to fish out part of the shell that fell in. Then, after adding some salt and pepper and scrambling the white and yoke together, he melted some butter in a pan (his mother had turned down the heat), poured in the eggs, and watched as the edges of the gooey eggs formed ruffles around the edges. After patiently waiting several minutes, he carefully flipped it, cooked the other side, then slid the concoction onto a plate.

Maintaining their conspiratorial silence, Leon’s mother helped him framed the eggs with slices of buttered toast. After adding some jam to the plate, young Leon slowly walked out of the kitchen with his triumphant offering, trying to suppress the big grin that wanted to burst forth. He got a nod of encouragement from his mother as he entered the dining room and finally approached his father. The eggs had looked a little shiny he remembered, perhaps not as well scrambled as his mother might have done, but they were well-cooked enough, he thought.

His father had looked up from his paper, glanced at his son with curiosity, gazed down at the eggs, then grabbed onto the plate. Little Leon had been reluctant to release his grip until he was certain his father had possession of it. Perhaps his father thought the boy was playing some kind of foolish game because Mr. Little finally jerked the plate away (eggs and toast miraculously sticking to the plate) and set it down in front of him.

What the grown up Leon remembered most was his father’s silence. Without speaking, Marvin Little just grabbed his fork and dug in, placing the first bite in his mouth with an urgent sense of purpose. Then, right away, he slowed down, and acting like a wine taster, rolled the food around in his mouth, pursing his lips, then smacking them, as if to extract every drop of flavor from the food. Finally he swallowed, still not looking over at his young son. But on the second mouthful the old man stopped. The playful tasting halted as he seemed to freeze in place. He just held the eggs in his mouth without chewing, like a robot someone had unplugged. Leon quickly backed away and ran out of the house, before he’d have to hear the final word on the breakfast. He had suddenly realized that the risk of his father’s response was too frightening to consider. His sensitivity needed to be protected, and from then on he never placed himself in any situation with his dad where he might be stuck wondering.

But marriage had brought Leon back into the danger zone. In a marriage you had to wonder. Wonder your worth, wonder if your respect matched theirs. Sarah had cut him deep and he had just frozen solid. He had stayed away from his own house just like he’d done as a child. Leon needed love, respect, and encouragement, and was pretty much paralyzed without them. In the end, he stood by helplessly as his wife and twin boys boarded the Pacific Northwest train destined for Chicago.

***

March 7, 1965

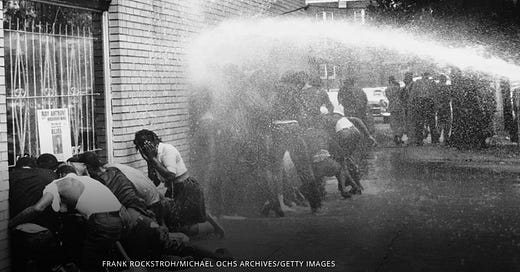

The TV coverage of the Alabama beatings was shockingly graphic. The state troopers could be seen running amuck, swinging their wooden batons against the heads, arms, and backs of the hundreds of people, old and young alike, who had assembled at the Edmund Pettus bridge just outside of Montgomery. Dee and Sarah watched the TV footage in horror, along with the rest of the country’s viewing audience. Their local minister, Chicago’s Father O’Brien, had given a sermon in support of the Negro protests a few weeks before the latest bout of trouble. He had mentioned how he and St. Angela’s were answering Martin Luther King’s call to come to Alabama, but Dee and Sarah knew they would surely have lost their jobs had they joined the marches. And they had the twins to think of. Who would look after the kids if one or both of them were hurt, or, for that matter, killed? The day before, they’d read how Dr. King and Unitarian minister from Boston, James Reeb, had been attacked, with Reeb sustaining a massive head injury. The group of defenseless black clergy had mistakenly ventured too far down a white controlled street.

“Hey, niggers,” the biggest White man called out as soon as he spotted the small group in front of a bar know for its KKK clientele. When Reeb and Dr. King realized their mistake they instantly turned and walked briskly back toward the church. But in that short time the Black men dropped their guard. With lightning- quick speed, one of the White men ran up to their group, pulled out a baseball bat and swung it with all his might, catching Reeb squarely in the back of the head. As the Black minister crumpled to the ground, the White men ran off gleefully. When Reeb’s friends came to his aid, the white attacker and his cohorts could be heard declaring their victory in the distance, hooping and hollering, Woweee, Home run thar, bro, and That’ll learn ’em.

As Dr. King was keeping vigil at Reeb’s hospital bed, Reverend Ralph D. Abernathy took over the protest, calling for an immediate march right then, right there, right in the middle of the night. When Abernathy and the congregation marched out of Brown Chapel with priests, ministers, other religious officials, the group included Monsignor Jack Egan, a prominent Chicago community organizer. Another priest offered to take Egan’s place, knowing he’d had recent health problems

“No you won’t!” said Egan as he stepped out into the night air. All night long the face-to-face confrontation continued, the dark street scenes illuminated intermittently with photo flashes from the many photographers who had gathered from around the world to document the civil unrest. Just beyond the two hundred or so policemen, whose shields reflected the glare of nearby street lights, stood a group at least two thousand rednecks, all yelling and cursing at the tops of their lungs.

“NIG- ger, NIG- ger,” chanted the unruly crowd. Egan could hear a lot of swearing too, yelled in unison through the front phalanx of cops, hurtful words like motherfuckers, black bastards, commies, etc. And somewhere from the side, just as they were rounding a corner, Egan heard someone yell loudly enough to register over the noise of the crowd, “I’d like to put a club through that priest’s skull.”

When the image of Dr. Abernathy and Jack Egan’s night march arrived over the Chicago Daily News wire service early the next morning, a reporter thought he recognized the Monsignor, who was well known as Director of the Archdiocesan Office of Urban Affairs. After getting positive identification from Father O’Brien that Egan was indeed in the photo, the reporter managed to get it featured on the front page. Its presence helped convinced many more religious groups from Chicago that they should also participate. And that’s when the south-bound buses and planes really started filling up.

Dee and Sarah saw Monsignor Egan’s picture in the newspaper and again considered making the trek to Alabama. They feverishly argued the pros and cons, but finally settled on joining whatever demonstration might occur locally, there in Chicago. It was during that intensity of the Freedom Marches that Sarah devoted her journal almost exclusively to documenting the struggle. She’d point at the coverage on TV and explain to the twins, “You see there, Jackson and John, that Black people are walking together. Our people, all marching together to get our right to vote in Alabama. That way we can have a say in who makes laws for us.”

Both of the twins were fascinated by the dramatic pictures on TV, but as three-and-a-half-year-olds, the concept of voting was beyond their comprehension. But Jackson surprised everyone when he pointed to the TV screen and said, “Dada running there!”

“No, your Daddy isn’t in Alabama,” said Sarah quickly. “He’s in Seattle. That’s a city far away from here. But he is a Black man...just like Martin Luther King.”

Dee couldn’t help feeling sad for Leon at that point. Here, on TV, the whole world was marching in the streets for freedom and fairness, while her daughter was keeping the twin boys thousands of miles away from their father. At that moment she decided to use her persuasive powers to help get Leon to Chicago, do whatever it took. She’d work her silent magic on her daughter, employ her voodoo if need be, to get Leon back with his family. There was no doubt that the kids needed him.

The next morning when the twins, Sarah and Dee ate their breakfast together, Dee added a prayer, spoken out loud so her daughter could hear it clearly. “God bless our people in Alabama, Monsignor Egan...the twins...Sarah…AND LEON...the Daddy of these sweet boys.”

————

Wow. What horrible happenings! It seems so long ago and far away. But, sadly, sometimes it seems like it's way too close ....